When botanist Daniel Solander went ashore 21 October 1769 at Anaura Bay in the East Cape district of the North Island of New Zealand, one of the first plants he collected was growing near the dwellings of the local people. The shrubs Solander saw were covered in clusters of bright red flowers and he named the plant Clianthus puniceus, recognising it as a member of the Fabiaceae or pea family. The Linnaean Latin means literally ‘blood red glory flower’ and tells us quite clearly about the impact of its blossoms on the newly-arrived Solander and his scientist boss Joseph Banks. The two Europeans collected and preserved 98 botanical specimens in the days that James Cook’s barque Endeavour was parked up at Anaura Bay, taking on wood and water and vast supplies of a wild celery whose antiscorbutic properties were going to enhance the health of the crew. Back on board the ship, Banks and Solander pressed their specimens between sheets of drying paper and artist Sidney Parkinson drew and coloured plants from the location which the Europeans heard as ‘Tigadu’ (Tolaga Bay). (Banks Journal, ed JD Hooker 1896) At the Natural History Museum earlier this week we saw Solander’s specimen list, Parkinson’s drawings of Clianthus puniceus and (crossing over to the Botany Department) one of the dried specimens of the plant that Banks and Solander brought to England in 1770. There is no colour left in the biological souvenir but its structural components are as palpable as they were 250 years ago to the hands and eyes at Anaura Bay. (Solander’s Clianthus herbarium specimen on NHM data portal)

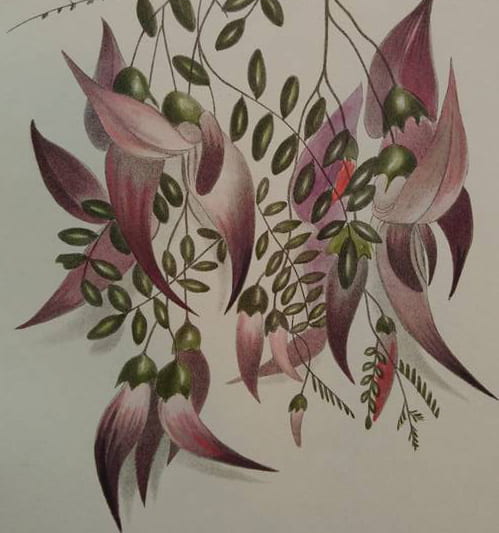

The red-flowering shrub is Kowhaingutu-kaka, literally ‘lips of the parrot kowhai’ or kakabeak, sometimes also called red kowhai. It was cultivated by Māori for its beauty but also because its nectar-filled flowers attracted tūī that could be snared while they were feeding. We think that Emily Harris drew both the red kakabeak and a what appears to be a mauve-flowered variety. A reviewer of her Nelson exhibition in 1890 was enthusiastic about her kakabeak: ‘A mantel drape worked in silk, with flowers of the red kowhai served to show how admirably adapted are our New Zealand flowers for the purposes of such decorative work.’ But when Emily handcoloured plate 3 of New Zealand Flowers, she used mostly pink and mauve hues, sometimes with spots of brilliant red, and the stripes of white that identify the plant as Clianthus puniceus. Did she ever, we wondered, paint her kakabeak flower blood red as per Solander’s description and her own decorative silk mantel drape?

We are in the library at Kew Gardens this morning to look at an unusual set of New Zealand Flowers, Berries and Ferns. It came to Kew in August 1900 as a gift from William Robert Ogilvie-Grant of the Zoological Department at the British Museum. The set is bound and coloured but lacks Emily’s signature. Did she forget to sign her name under the artist’s palette on each of the three title pages, or are we looking at the work of another colourist? We’ve seen one other coloured and unsigned set at Nelson Provincial Museum. That set poses even more questions than Kew’s because someone (not Emily) has imposed paper labels with Māori names on eight of the plates and the books have been disbound and cut up, presumably for mounting and display as single prints. The question connecting Nelson’s set with Kew’s is: who did the colouring?

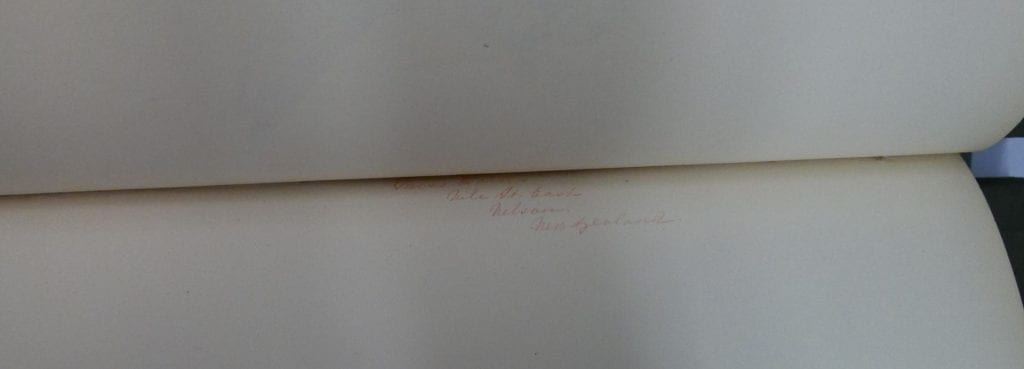

We find the answer almost immediately. First, the painting is unmistakably Emily’s work, colour and brushwork are identical with other sets we’ve seen. And as we page through NZ Flowers we find on the inside back cover in faint red pencil the following inscription written vertically near the gutter edge:

Emily Harris

Nile St East

Nelson

New Zealand

And sure enough, her signature (but not the address) appears again on the inside back cover of NZ Berries and on the inside back cover of NZ Ferns, each time in that faint pencil and in the same position.

Now we notice something else about Kew’s set: Emily’s modelling of each plant across the three books is detailed and careful, a kind of deluxe edition noticeably different from most other sets we have been able to see. If Nelson’s plates display the same care, it seems likely that we are looking at early colourings linked by acute attention to detail and signatures placed in less obvious locations. The Nelson set has lost its back covers, which may explain why the remaining plates appear to be unsigned.

Our morning at Kew is further enhanced by one of those moments of pure serendipity that occurs from time to time. On duty at the desk as we walk in is New Zealander Anne Marshall, ex University of Canterbury MA English class of 1978. We talk with Anne and her colleague Anne Griffin about William Robert Ogilvie-Grant and his gift of Emily’s books to Kew. Why did an ornithologist take an interest in botanical flower painting? Is there a connection with New Zealand or with Emily herself? There is more work to be done but for now we are happy to have solved the question of signatures and to have found a deluxe set of Flowers, Berries and Ferns in mint condition at Kew Gardens.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis

what a coincidence to find a Canterbury alumna at Kew Library!

Good sleuthing.

just a thought but NZ flora does have a few quite specific plants, in particular the scarlet mistletoe, that from an ornithological point of view opens when the bird, usually a tui, historically also a huia ‘opens’ the flower with a twist of the beak where it springs open.

lovely article, and how lucky Kew Gardens!! one day.