Sometimes the answers are right there. It just takes a while to see them. We’ve read the William Bryan passenger list, 7 names in the cabin, 141 men, women and children in steerage. The Harrises are there: Harris, Edwin Painter 32; Mrs 30; Boy under 7; Girl under 7; Girl 10 months. In fact Edwin and Sarah were both 34 in 1840, and their youngest child was almost 18 months by the time the William Bryan sailed out of Plymouth sound. Birth dates were more approximate for early Victorians than in our data-precise age. Captain Alexander McLean did however need an accurate account of the numbers he was carrying to New Zealand, and the ages of the children were indexed to food and water rations along the way as well as available space below decks. A child under 12 months was assigned no shipboard rations on the assumption that the mother was breastfeeding and therefore supplying her infant’s needs.

Why did Edwin take his pregnant wife and three small children to the other side of the world in steerage? Socially the family belonged in the cabin with Plymouth Company officials and gentlefolk. ‘Mr and Mrs Harris are musical’ observed ship’s surgeon Dr Henry Weekes, ‘he plays the guitar and flute and she sings with taste.’ ‘Mrs Chilman the Cabin Lady was confined a week after myself of a still-born boy,’ Sarah wrote to her father and sisters, ‘we were always very friendly on board.’ And why did Edwin give his occupation as painter when his background in surveying and civil engineering might have been a better fit for what lay ahead? Sarah’s own words, written decades after the voyage in a memoir for her children, begin to answer these questions:

Catherine was born in Somersetshire, Dulverton, where we were two years during the surveys made by your father for the Reform Bills. Your father had been all through the County of Cornwall with the Commissioner Dawson for the same purposes. We were prospering and likely to do so but for a very unexpected trouble in a will, concern which to oblige a brother in law of mine whose dishonourable conduct quite ruined us at this time.

New Zealand was much talked of and Governor Hobson who was a friend of the Rendels wrote them from N.Z. saying if Mrs Rendel’s brother would come out to N.Z. he would find plenty of work in the survey and for him. I did not feel willing to go but Edwin was bent on going and all his friends thought it a fine opening for him. So there was great preparation made as to outfit useful instruments for surveys and many useful handsome presents from friends who we might well never see again. So at length all was ready and we left England for New Zealand November the 19th 1840, with three children Corbyn, Emily & Catherine. (Letter #1)

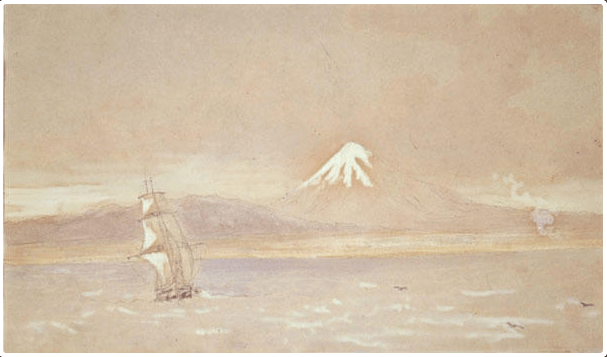

I did not feel willing to go. But she had to, and they embarked for New Zealand with a letter of recommendation to Hobson and not much else. Sarah was able to pay two of her fellow passengers, Mrs Jane Crocker and Mrs Ann French, to nurse the newborn baby and 18 month old Katie. But it must have been hard going for the family. Sarah’s letters make it clear that losing the baby was a terrible blow and her postnatal illness had been near fatal. Edwin did indeed paint during the voyage. Two small and delicately drawn watercolours of the William Bryan in Cloudy Bay and off Taranaki are now in the Puke Ariki Heritage Collection in New Plymouth. They were donated by Emily Harris and her sister Mary Weyergang in 1919 and 1920.

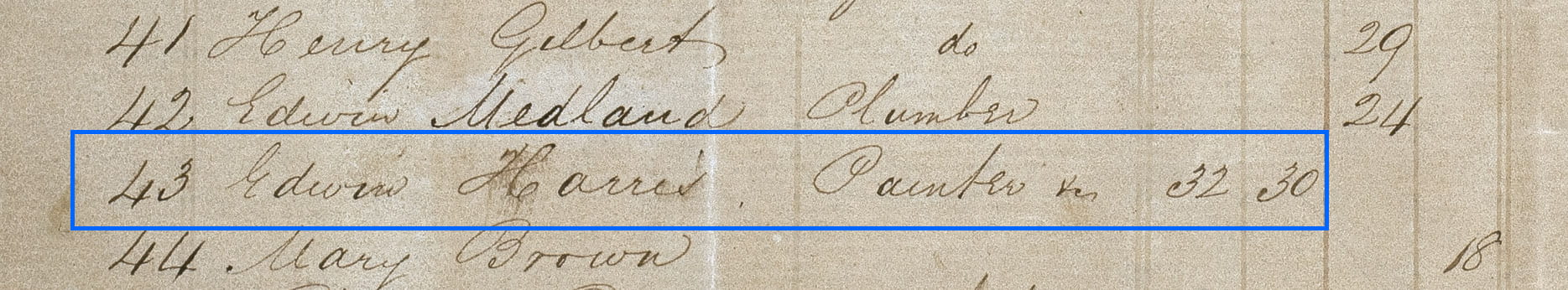

Puke Ariki also holds Plymouth Company records (which we knew), and original manifests for the first six emigrant ships to new Plymouth, which was a revelation. Not one but three copies of the William Bryan manifest came into view, the top copy signed by Henry Weekes and Alexander McLean. Also present was a summary of passenger statistics signed and dated by Weekes and George Cutfield, Principal Company Agent and leader of the expedition. Kathryn Mercer, Information Services Officer at Puke Ariki, took a look at the manifests for us and reported her initial findings:

The three manifests are recorded on printed forms on heavy cream trimmed laid paper. They are designed to be viewed in landscape format. Opened out, they measure 16 1/2 inches by 26 1/8 inches. They were designed to be folded in half, width-wise, like a booklet. The printed text is in black. Much of each page is taken up by tables, outlines ruled in red (now brownish), with blue lines for listing the passengers, which is done in black (now brownish) handwriting.

Two of the copies are in quite good condition, but one has come apart down the main fold and is a darker cream colour. Some repairs have been done using butterfly tape circa 1980s. One was folded in half five times, small enough to fit in a pocket, and is browned around the outer folds.

The hand that tabulated names, occupations and ages is probably that of a clerk in Plymouth. But there is a difference between the handwritten documents and the published lists of emigrant names familiar to us from books and websites. Those who transcribed the William Bryan manifest for centennial celebrations in 1940 must have alphabetised each list, because what we are looking at is the numbering 1-45 of embarkation orders, and Edwin Harris is #43. It seems that Edwin’s decision to emigrate was made late in the piece and the cabin, with room for only half a dozen emigrants, was probably full.

There is a squiggle after Edwin’s occupation. With some squinting and by consulting the other copies, we can see that what the clerk wrote was actually ‘Painter &c.’ The old abbreviation for ‘etcetera’ was omitted by the 1940 transcribers, replicating the clerk’s elision of whatever else Edwin had listed (surveyor? draughtsman? civil engineer?) and the column was too narrow for anything but that &c. Only the painter Edwin Harris stepped into the record being confirmed on the beachfront in New Plymouth 5 May 1841 ahead of the William Bryan’s departure for England. But it was the &c (surveying, draughtsmanship) to which Edwin would turn when it came to the immediate problem of feeding his family in the new world. Hobson proved unreachable in Auckland. In June 1841 surveyor Frederick Carrington, laying out the township that would become New Plymouth, took Edwin on at two pounds a week.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis, Kathryn Mercer, Brianna Vincent