Alfred Domett has the last word on the English climate:

‘O horrible, horrible, most horrible.’ For the last month or six weeks dullness-cloud and fog – perpetual Scotch mist or rain – spitting not pouring. ‘Adam loved God – but went apart and dwelt in the shade’ – So Jeremy Taylor began one of his sermons once. And precisely that seems the fate of one who comes back to England after long sojourn in New Zealand – One seems always in the dark. I try to give the natives (I mean our native Anglo-Saxons) an idea of our feelings about it by telling them it is just as if they were to go suddenly and live altogether underground – Would any amount of fine furniture or indoor luxuries or profusion of gaslight make up for the loss of the daylight? But the wretches only smile – with a fatuousness of perfect content with their lot which is truly irritating if not disgusting. Think of long rows of mean houses of the dirtiest brick with neutral tinted deadlooking skeletons of trees protruding their ugliness here and there – streets always muddy or sloppy in spite of indefatigable scavengers and big carts of mud-soup ladled into overflowing in every quarter – all fading in short vistas into sullen gray or yellow fog – people with an air of stolid endurance hurrying along under umbrellas – their waterproof coats the only shining things in their existence. (Letter to Arthur Atkinson, 27 Nov 1872).

Domett was back in London after 30 years spent in New Zealand as colonist, surveyor, politician and poet. The letter goes on to report to Atkinson on the progress of Domett’s recently published epic Ranolf and Amohia: A South-Sea Day-Dream. The poem, an encyclopedic 511 pages (it would swell to 646 pages and two volumes in the revised edition of 1883) is famously unreadable. Critic Patrick Evans once likened it to a stranded whale that lies rotting on the beach of New Zealand literature, an embarrassment that no one knows what to do with. Domett would probably have enjoyed the epithet, if not its implications.

There are better ways of engaging with Ranolf and Amohia than trying to follow its labyrinthine digressions or deal with its dodgy cultural politics. Sometimes a single candela can illumine dark matter. From Ulysses take: ‘the heaventree of stars hung with humid nightblue fruit.’ From Moby Dick (The Whiteness of the Whale): ‘marbles, japonicas, and pearls.’ From Ranolf and Amohia, we could try the bush. Perhaps this:

No tangle of convolvulus to twine

Into rich coronals of cups aglow

With deep rose-purple or delicate white

Pink-flushed as sunset-tinted snow;

or this:

No clematis, so lovely in decline,

Whose star-flowers when they cease to shine

Fade into feathery wreaths silk-bright

And silvery-curled, as beauteous.

But it is what comes next that jolts the synapses:

And they knew

The early season could not yet

Have ripened the alectryon’s beads of jet,

Each on its scarlet strawberry set,

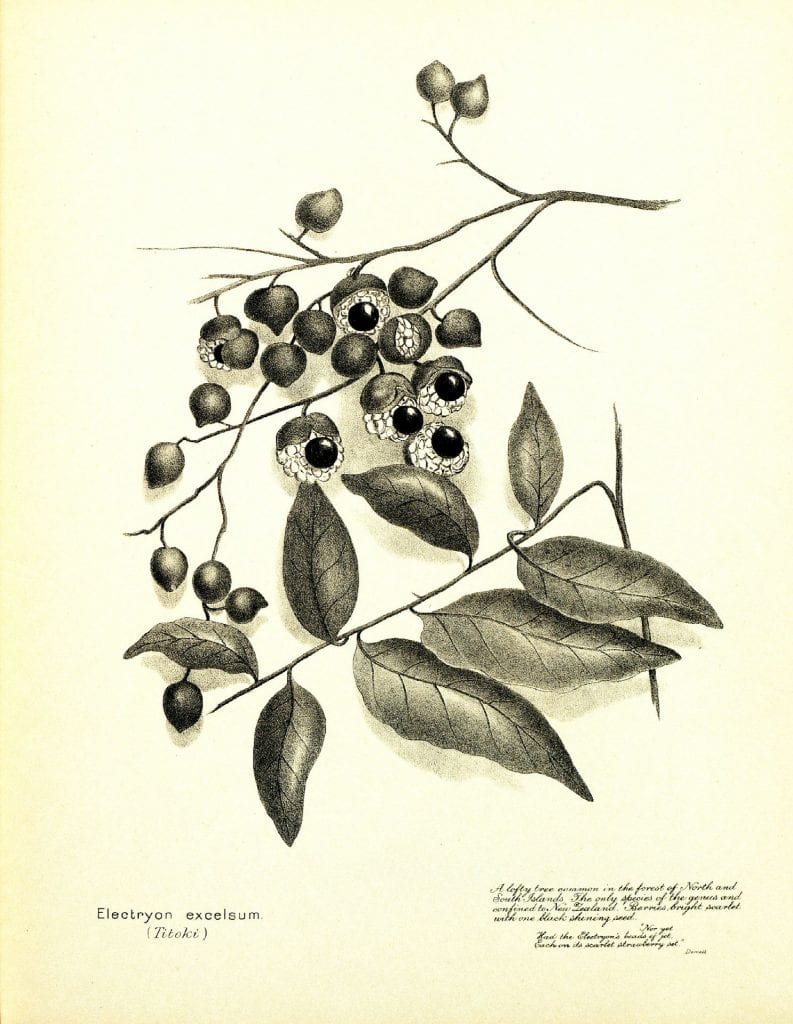

This is what Emily Harris remembered, writing captions for her book New Zealand Berries, when she got to tītoki. There had been an earlier plan for including poems with the drawings of native flora. ‘I have got two poems ready for the books,’ she wrote in her diary in 1889, ‘but I do not get on with the illustrations although I know exactly what I want.’ She dropped the poems in favour of descriptive notes for each of her 36 drawings. But here, at plate 8 of Berries, she allows a single glint of poetry to appear:

Electryon excelsum.

(Titoki)

A lofty tree common in the forest of the North and South Islands. The only species of the genus and confined to New Zealand. Berries bright scarlet with one black shining seed.

‘Nor yet

Had the Electryon’s beads of jet,

Each on its scarlet strawberry set.’

Domett.

If Emily had any doubt as to Alfred Domett’s sources she could have turned to the extensive notes on Natural Objects and confirmed that he was using (besides first-hand observation) JD Hooker’s Handbook of the New Zealand Flora (1864-67). Domett’s detailed profiling of convolvulus and clematis in the bush walk that opens the 1872 edition of Ranolf and Amohia is echoed in Emily’s New Zealand Flowers (plates 4 and 6). ‘Convolvulus Sepium (Panake). A slender climbing plant growing over shrubs and small trees at the edge of the forest. Flowers white.’ ‘Clematis indivisa (Puawhananga). Some Authorities leave out the h in Puawhananga. A large strong woody climber abundant throughout New Zealand festooning trees especially on the skirts of the forest. Flowers white.’

But it is Emily’s description of the tītoki berry and the lines from Domett that call attention to plate 8 of New Zealand Berries. In uncoloured sets of the book, her words and Domett’s give us a double flash of red (scarlet, strawberry) that saturates the page. In handcoloured sets, verbal and visual registers play together. Does Emily’s painted rendition match the scarlet strawberry of the mind’s eye? Because each handcoloured set is slightly different, eye and mind must look again each time for the shining black seed and its bright red fruit. This is the pleasure of colour, never fixed, always in need of another look.

One last detail. Why does Emily Harris reword Domett’s lines? ‘Not yet / Have ripened the Alectryon’s beads of jet’ has become ‘Nor yet / Had the Electryon’s beads of jet.’ Perhaps Emily had a different version of Ranolf and amohia to hand. (could she have seen a periodical or newspaper excerpt of the poem?). Or perhaps she is quoting from memory. Others before and after her have played variations on the tītoki’s Latin binomial (Alectryon excelsus, Electryon excelsum). It is also possible that Emily Harris adapted Domett’s lines to suit her own sense of how the quotation should run. The scarlet berry and its shining bead of jet will go on with their eye-catching business a while yet.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis