We know where Emily Harris’s New Zealand Mountain Flora is now. It was an artist’s mock-up of the book she planned to publish, couldn’t afford and then sold to her English cousin Lord Stuart Rendel for his private collection. By way of the estate of collector Kenneth Webster, the Alexander Turnbull Library was able to purchase Emily’s collation of paintings, text and poems and bring it back to New Zealand in 1970. The book contains eight poems and 30 watercolours of alpine plants, several with embedded scenes of their habitat, and Emily herself considered it a high point of her artistic production.

But how exactly did New Zealand Mountain Flora make its way to London and into the collection of Stuart Rendel (1834-1913)? There are at least two answers to the question. The first is centred on the moment in 1902 when Emily gave up her initial publishing plans for the book. The idea had been to find 200 subscribers. New Plymouth collector WH Skinner noted in his diary: ’22 April 1899 Attended an exhibition of N.Z. wild flowers paintings by Miss Harris of Nelson. Put my name down as a subscriber to her work on N.Z. Mountain Flora to be published at £1.1.0.’ Three years later, visiting Emily in Nelson, Skinner observed: ‘7 February 1902 Called again at Miss Harris’ and found her home, stayed a considerable time going over her studio I’m afraid she will never have the means to publish her work on the Mountain flora of N.Z., poor soul. She must be very poor but she puts on a brave appearance.’ Lady Ellen Rendel, writing to Emily 9 August 1902 from England, was sympathetic and ready to take up her offer of sending what sounds like substantial work. The handwriting is difficult to make out but Ellen Rendel’s drift is clear enough: ’If you have not sent the drawings do you think it is quite [one word]? safe? right?] unless they can be sent by hand. I shall be so sorry [one word?] and disappointed you were not able to sell them then of course delighted to possess one at the 10 guineas you mention.’

So it is possible that Mountain Flora passed into the keeping of the Rendels as early as 1902. But a second possibility presents itself in letters Emily wrote to Minister of Education George Fowlds in 1910 and their conjunction with letters written at the same time from England by Lady Rendel and Emily’s Nelson friend Catherine Ledger.

To Fowlds, Emily wrote 27 May 1910: ‘‘I am preparing another book the same size as those I sent you but much better, “New Zealand Mountain Flora”, I began it 10 years ago but have never been able to afford to publish it, now when finished I may perhaps be able to do so, if the estimate is not beyond my means. I will send you two or three pages by post if you will let me know whether you would like to see them.’ From Ellen Rendel at 10 Kensington Palace Green, Emily received a note acknowledging receipt of a letter introducing Mrs Ledger who was bringing presents for the Rendel grandchildren. The Ledgers were in London and Catherine reported 15 June 1910 on the visit with Ellen Rendel: ‘Two days ago we went to call on Lady Rendel, we found her most charming and kind, just like your own dear self, she gave us chocolate out of such pretty Wedgwood cups. Her husband and eldest daughter were out in the country as he can not sleep well. They keep two motors, also a carriage and pair. […] I feel sure that Lady Rendel will help you to bring out your book of Alpine Flowers.’

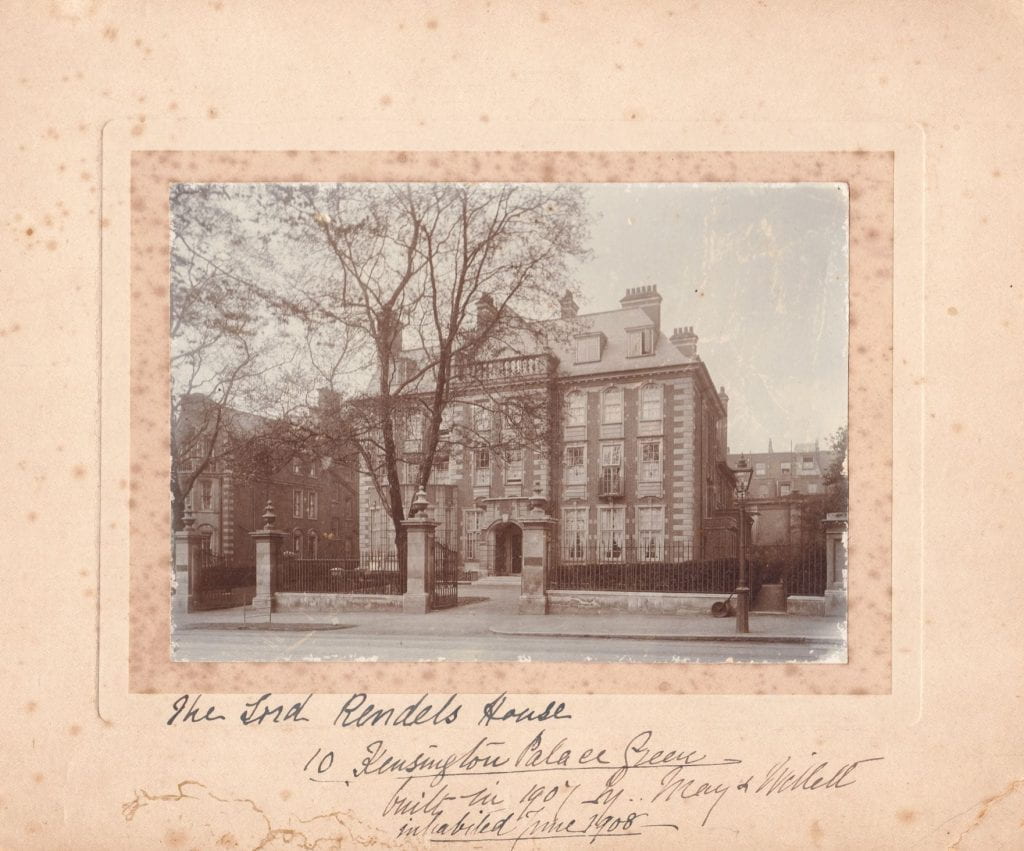

From this we can infer that the mountain flora project was alive and well, though still in need of a sponsor. But both Rendels died before the outbreak of war in 1914 and Emily must have realised that her chances of publishing were gone for good. When she wrote to Dr Rendle (no relation of her own Rendels) in 1914, alerting him to the location of New Zealand Mountain Flora, should he want to see it, she would have known that the book was either at Hatchlands, the family’s country residence in Surrey, or in the library of the grand house at 10 Kensington Palace Gardens. The address is still one of the most expensive in London, part of a Crown Estate dating back to the 1840s. Stuart Rendel’s father James Meadows Rendel leased the house in 1852, soon after it was built. Stuart acquired the lease himself around 1907 and was in residence by June 1908, according to an inscription on a photograph of #10 in the Harris and Weyergang Album Photographique. Today the property, much reconfigured and sporting one of London’s 4600 mega-basements, is leased by billionaire John Hunt and sits behind a gate through which google Streetview cannot penetrate.

We strolled to Kensington to take some photos 109 years (almost to the day) after Catherine Ledger’s visit.

Catherine had lots to say about London, at the time plunged into mourning by the death of Edward VII the previous month, and about the details of her visit with Lady Rendel:

She would have us put our names in her visitors book, also in her birthday book. My name was next to Herbert Gladstone’s as we were both born on the same day. She has some people from Canada staying with her, they had just returned from Paris. Lady Rendel did not like their fashions at all, their hats were as big as sunshades. I must tell you about them Later on. London is very sad just now, nearly every one in black or black and white, white hats trimmed with black feathers and ribbons and gauze. Black hats with white ribbons, plumes also heliotrope. That seem to be the three colours worn for every thing. […] The Londoners feel the death of the King. We heard about it first at Montevideo and at Rio the flags were flying half mast. Everywhere Nearly everyone on board the steamer put on something black. I am all right in my black silk, a black and white [word missing?] in my bonnet with a new black lace scarf. Lady Rendel wanted to see Joy as there is a Joy Gladstone and she wanted her to put her name in her birthday book but Joy was too shy. But when I go again I will take her with me.

Everything is very swell inside and outside the house, lovely trees and lawns, and greenhouses, electric lights, the chine and pictures just a dream of beauty.

I have so much to tell you I hardly know where to begin. We went to hear and see Rigoletto, Madame Tetrogini, [?] it is too high tragedy to please me. Oh! this is a wonderful place this big London, no end of things to see and do. Grand turn outs, splendid motors, lovely horses and carriages. Now dear old friend with much love adieu, yours with kind wishes, Believe me ever yours, Catherine A. Ledger.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis