The pencilled comments in Puke Ariki’s copy of Taranaki: A Tale of the War by Henry Butler Stoney are unanimous in their condemnation of the book. ‘Bunkum,’ says one. And: ‘It is rarely I have read a book in which I have not found some passage worthy of remark or of transcription, but this is such Minerva Press twaddle as to be utterly devoid and unworthy of either.’ To which someone has added: ‘quite correct, all Bosh.’

What has stirred up such vehement response to Captain Stoney’s work, published in Auckland in 1861 and sometimes identified as the first home-grown New Zealand novel? Perhaps it is the mix of historical military dispatches and an unlikely romance plot that angers these readers. Minerva Press specialised in sentimental and gothic fiction, and Henry Stoney would probably have been pleased if circumstances had presented him with a London publisher for his novel.

Instead, WC Wilson, proprietor of the Southern Cross newspaper (later the New Zealand Herald) took on the job, and Stoney did his own proofreading, not always with his eyes on the details of the text. The romance plot relies heavily on the complications of mistaken identities, some of which outfox even their author. The grumpy penciller has covered the margins of his copy with corrections of fact, spelling and punctuation.

But Stoney’s awful novel has one saving grace. Its author knew Emily Cumming Harris and the Des Voeux family she worked for in New Plymouth during the war. In a letter to her mother 5 Dec 1860, Emily records her meeting with Stoney and fellow officer Thomas Miller on the morning a party set out to visit Glenavon, the Des Voeux farm on the northern bank of the Waiwhakaiho River:

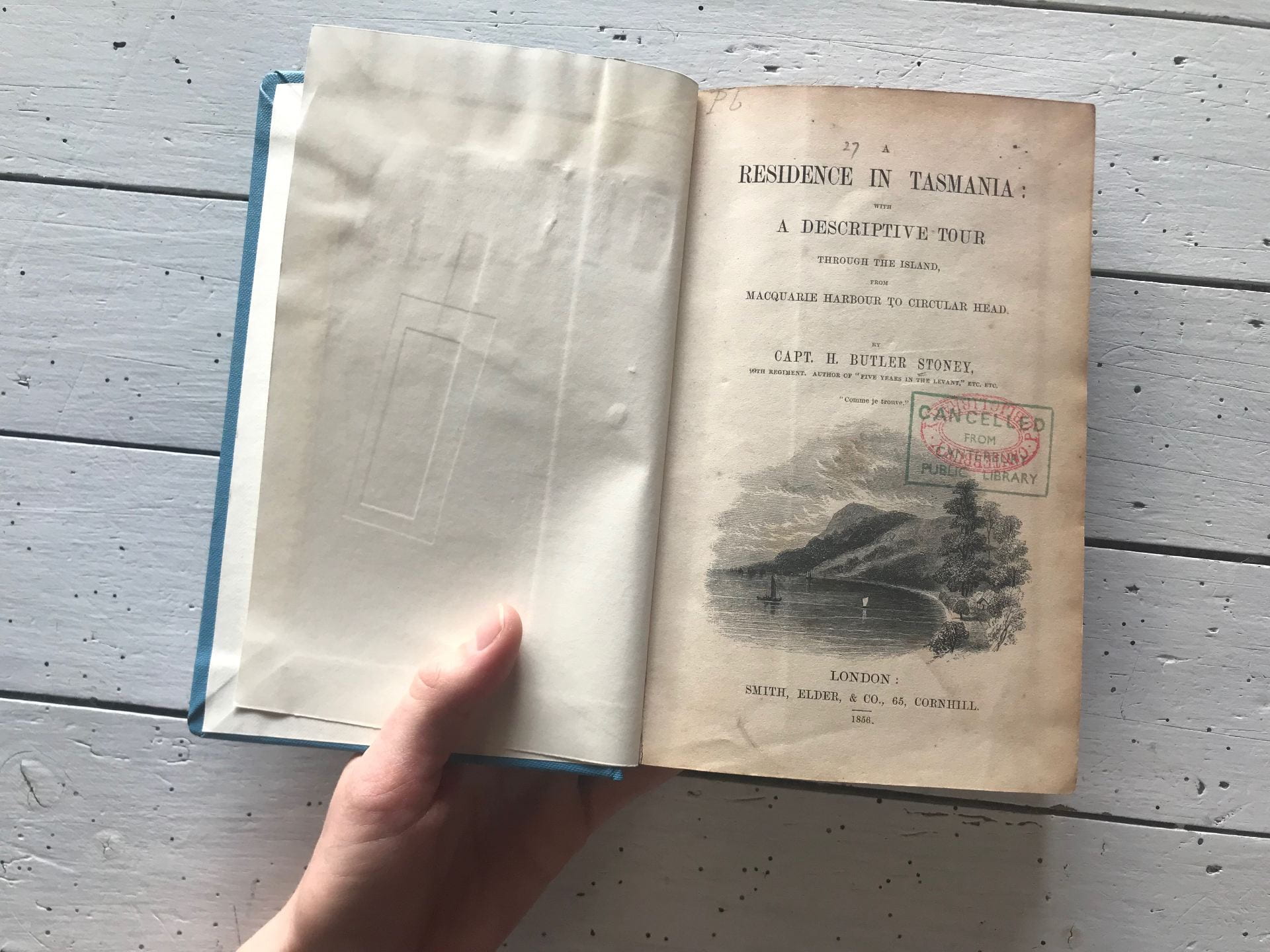

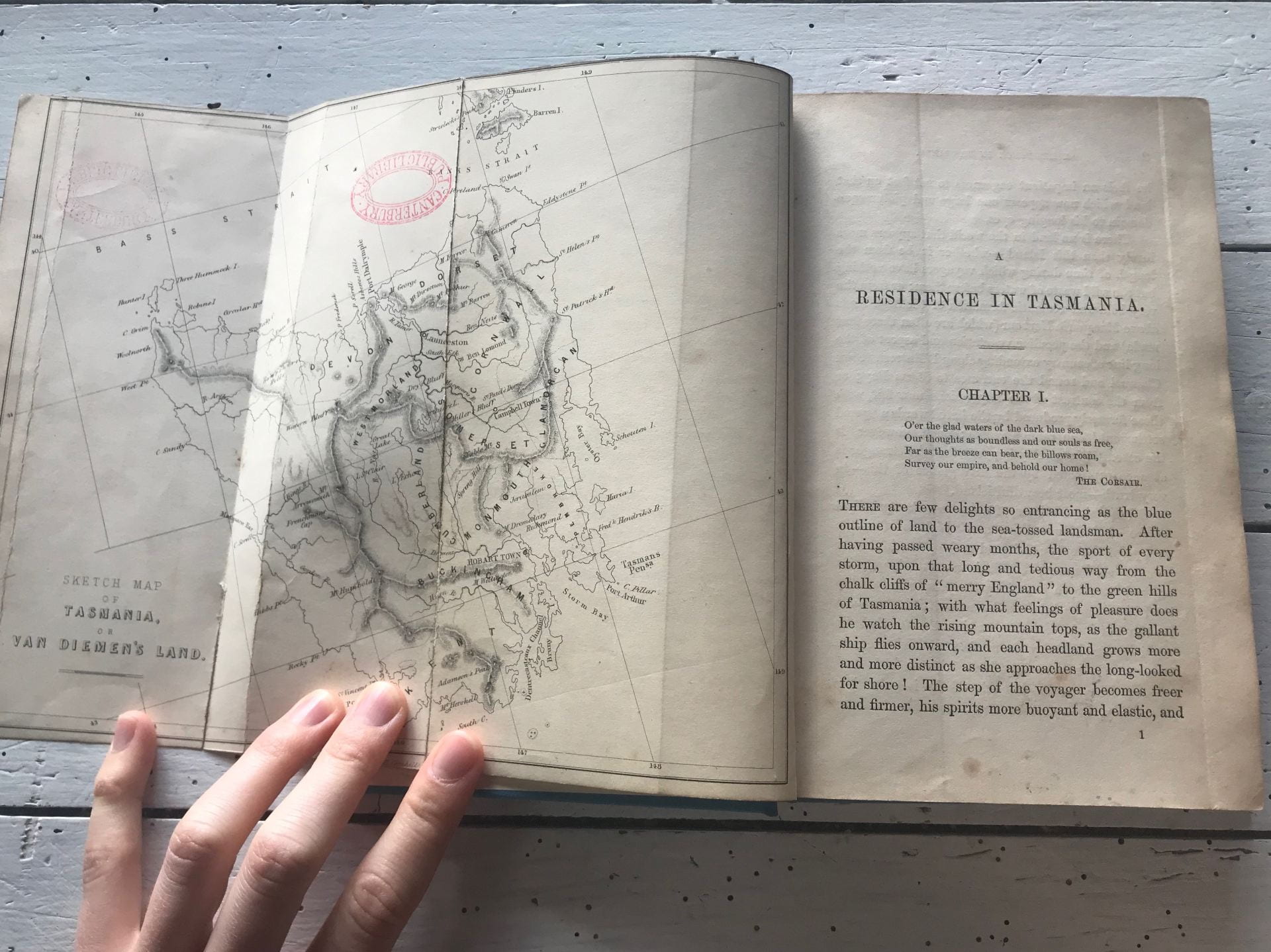

But I must now say something about the gentlemen; they were strangers to me Capt. Stoney and Capt. Miller. The latter you will remember so bravely tried to rescue poor young Wakefield from drowning and nearly lost his own life in the attempt, the former I had never heard of until a few days before when Mr D. V. brought two books written by him, one on Tasmania the other on Melbourne. They were beautifully bound in blue and gold, nicely illustrated and very interesting, so I was quite prepared to see a clever man but I am sure I never [met] with any one so agreeable besides being very handsome.

Emily recounts the trip to Glenavon not once but three times over, adding details for different readers with each retelling. Arising directly out of the incidents of that day (including an interlude in the garden dell with the gallant Captain Miller) comes her elegiac poem ‘Lines Written on Visiting Glenavon during the War 1860.’ Arising from the same events comes a good deal of the backgrounding for Stoney’s novel, which features a family called Wellman who live on an estate called Glenfairy on a river called the Matu Taku. Upriver from the Wellman’s is the even grander estate of the St Pierre family, whose members include a marriageable daughter and a dashing military cousin who arrives from India. (Is it just coincidence that ‘pierre’ is French for a stone?) Upriver again from the St Pierre’s is the equally extensive estate of Mr Dickson, fortunately without offspring to further complicate the plot that Stoney sets in motion against the campaigns of the war.

What is going on here? Why has Stoney transplanted the farms of Captain Henry King (Brooklands) and Charles Brown (Ratanui) to locations on his fictionalised Waiwhakaiho River? The simplest explanation is that Henry Butler Stoney, a younger son of Irish landed gentry, was intent on framing his story about the war in Taranaki as a tale of investment capital and aristocratic privilege waging a struggle against indigenous insurrection and military misadventure. Much of his novel is devoted to nostalgic reveries about the fetes, balls, parties and picnics held by the local gentry on their fine estates before the interruption of the war. At the novel’s conclusion, and unlike their real-life counterparts, Stoney’s characters head back from Hobart after hostilities end to re-establish their homes and prosperity in New Plymouth. Like the good Victorian that he is, Stoney is primarily interested in inheritance and property rights and imposes his views on the Taranaki situation as he finds it, clearly entranced by the Des Voeux, Richardson and King families and their pretensions to local squirearchy.

The Des Voeux and Emily herself were not taken in by Stoney’s views or by his prose style. Emily reported of the work on Tasmania that Stoney loaned them: ‘It was handsomely bound & illustrated, Mrs Des Voeux and I soon skimmed through it with great curiosity & interest but we came to the conclusion that the poetical quotations at the head of each chapter were the best part of it.’ It would be interesting to know their opinion of the novel Stoney made out of his sojourn among them. We can be sure at least that they would have agreed with his criticism of the British commanders in Taranaki. Here is one example of such a moment in the novel, where Stoney weighs in on the side of good sense against a proclamation by his superiors ordering lights to be left in empty houses in the event of a night attack on New Plymouth:

Constant alarms and rumours were daily afloat of intended attacks on the town; and on more than one occasion, these alarms coming after dark, threw the town into the most dreadful confusion and distress, whole families rushing from their beds, half-dressed, to seek refuge in the places appointed as those of safety: a most imprudent arrangement, for had an attack really taken place, the very measures ordered to be resorted to would be the cause of destruction to most, for in place of remaining in their homes, fortified even in the simplest and most temporary manner, and thus checking the advance of a foe, they left their houses open, with lights in the windows, as by the orders published, and rushing wildly through the streets, would have given an opportunity quickly to be taken advantage of if an onslaught were ever made; for any one acquainted with the mode of savage warfare must know that the attack would be sudden and rapid, from several points; not delay to tear a house down if it were safely closed, but, dashing through the streets, they would only tomahawk those in their way, and force a passage, and retreat from the town.

It was not considered in this light until two or three of these alarms occurred, when the confusion was so great, and the folly of the orders so apparent, that it was determined to remain and barricade their homes. (106)

The spectacle of New Plymouth lit up after dark by candles and lanterns in empty houses under night attack had no tactical benefit for the besieged town. That it was something Emily Harris and her father Edwin observed at first hand is key to understanding the memorial Edwin made of his son Corbyn’s death at Waitara in July 1860. It seems that Emily’s poem about Glenavon and Edwin’s painting of New Plymouth under night attack are creative responses to put alongside Captain Stoney’s fantasy of love and war.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis

Thank you Betty,

do we have any idea of who the writer in the margins was?

Does Puke Ariki have any provenance for their copy?

I don’t think so Ricci! This would be a question to ask the Puke Ariki team…