What made Edwin Harris draw and paint the view from Marsland Hill in New Plymouth 3 August 1860? And what made him produce multiple versions of the scene that shows troops from the 40th Regiment being brought ashore and lined up to march on Māori positions near Waitara, 16 km to the north of the besieged town? Certainly Edwin is depicting history, a moment of significance in the settlement where he has lived and worked for almost 20 years, raised a family and bought land to clear and farm. He is socially and politically invested in the view he represents, a home place under threat, an outpost of empire about to receive reinforcements and a new commander from Melbourne. It’s an important day in New Plymouth.

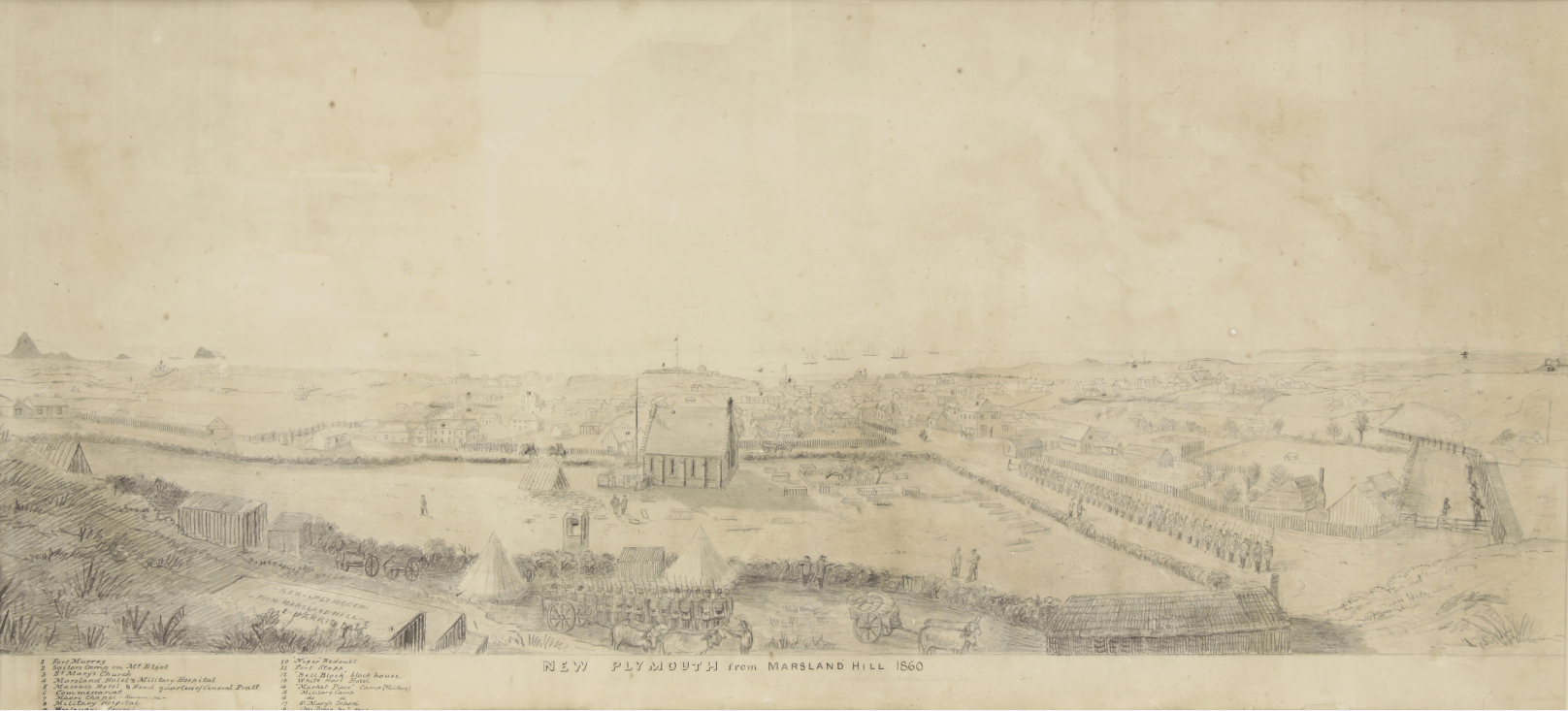

We can assume that Edwin drew the scene from life. He was there in the town 3 August 1860, a Private in the Taranaki Militia with time that day to climb Marsland Hill to get a good view of the disembarking troops. Here is his drawing of the panorama spread out below him:

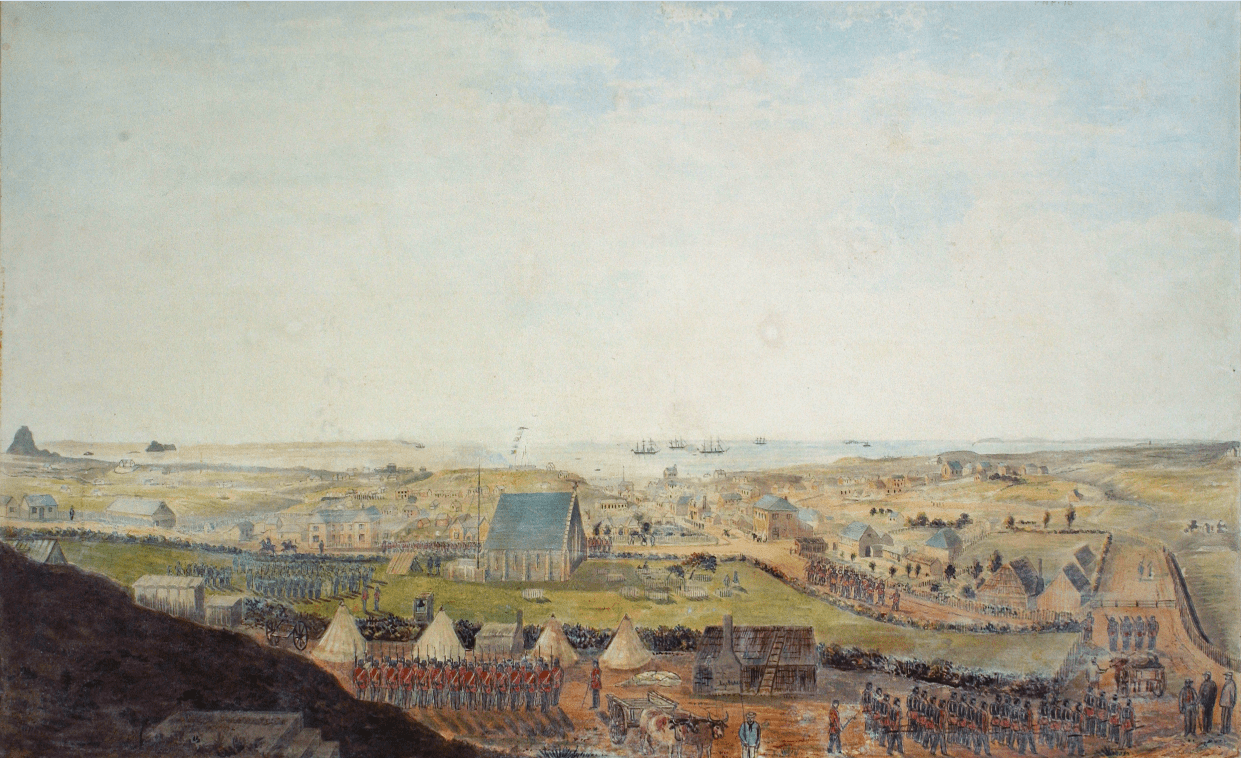

And here is the lithograph that was printed and published in Melbourne a few months later, then advertised for sale in Nelson (and probably New Plymouth) in March 1861. We don’t know how big the edition was, but the production of the lithograph indicates that Edwin anticipated a market for his record of the landing.

Like the sketch, the lithograph has a legend that identifies 18 sites of interest in the settlement, many of them military, several pointing out churches, chapels and the tomb of Charles Armitage Brown Senior on the hillside below the artist’s location. Lithograph and sketch are closely connected, and one is probably the origin of the other.

But Edwin Harris’s depictions do not stop here. Also at Puke Ariki in New Plymouth is a watercolour of the scene, and just for good measure another showing the disembarkation from a viewpoint beyond the five ships in the roadstead. Did Edwin go out to the ships himself to get this view or is he working imaginatively with the events of the day?

It is only when we consider the version of Edwin’s painting that was made into an optical amusement that something like a reason for the multiple works becomes apparent. When TSB Bank bought the painting at auction in 2008, nobody knew why its surface was a mixture of collaged figures and relief cut outs. Camilla Baskcomb, paper conservator at Auckland Art Gallery, assessed and conserved the previously restored painting and realised it was an optical amusement, designed so that a light source placed behind it would throw actual light towards a viewer, lighting up windows, doors, soldiers’ tents and the sun which turned into a half-moon out over the sea.

Edwin saw lighted windows in New Plymouth, though not on the evening of 3 August because there was no alarm on that day to send women and children running up the hill to take shelter in the barracks. Nor was there a half moon on that date. And contemporary accounts of the disembarkation tell us the troops and their commander were all ashore by 10 am that morning.

So what is Edwin Harris up to? The answer lies literally in front of us, a key point in the artist’s representation of the panorama before him. At the foot of Marsland Hill, below Charles Brown’s tomb, is St Mary’s Church with several graves and small figures going about their business. Three days before he sketched the view from the hill, Edwin Harris had buried his only son, a carter attached to the camp at Waitara. Hugh Corbyn Harris, 25, was ambushed and shot on the beach while collecting firewood for the army kitchens 28 July 1860. His body was returned to New Plymouth by boat and taken to the chapel at the Kawau Pa. His funeral at St Mary’s 31 July was attended by settlers and military, and though the townsfolk were loud in their condemnation of the ambush, the family’s public statement of grief did not extend to blame or calls for revenge. None of the graves Edwin shows in his depictions belongs to Corbyn, but like almost every other site in the view from Marsland Hill, St Mary’s and its churchyard reference the pain of a grieving father. We don’t know when Edwin repurposed one of the Marsland Hill watercolours as an optical amusement. We can guess that the addition of collaged figures of women and children on the hill and the holes cut in the ground of the painting to show light through windows and doors is a deliberate attempt to blend history with a memorial to the lost son. The tents of soldiers are lit up from within (war is encamped in the town). The moon shines on a silvery sea, the only one of Edwin’s representations that is a night scene. The lights glow through translucent backing paper, perhaps a message of hope in a dark time.

Nobody knows where Edwin’s optical amusement spent the years between (say) 1860 and 2008, when art dealer Brian Groshinski saw it in a Melbourne auction catalogue and purchased it for resale. Brian’s guess is that the painting, much deteriorated, had been languishing in the Berry Estate in Melbourne for many years. Today it is in New Plymouth again, close to the scene it represents: Marsland Hill is visible from the upstairs windows of TSB Bank’s head office on Devon St East. When the LED lights behind the picture surface are turned on, Edwin Harris’s memorial to his son illuminates the difficult past of Taranaki.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis