In her diaries from the 1880s Emily Harris tells two stories about burning. The first concerns the destruction of a diary when she was a young woman in Taranaki in the late 1850s. She is painfully conscious of the loss her action imposed at the time and regrets it still:

Well, long ago, some seven & twenty years, in the days of my youth — what an age ago! — and yet now I seem to be just beginning to find out what I can do & how to do it. If I could only have had the advantage then that young people have now, instead of groping in the dark & longing for what we know not, what a different career would have been mine. Oh that diary begun when I was young and life was all before me. I wish I had gone on with it, if only for a few years, what a true record it would have been of a colonial girl’s life with romance enough for more than one novel, what a graphic account of the Maori War, what we did & suffered & went through in those days. But to return to the diary.

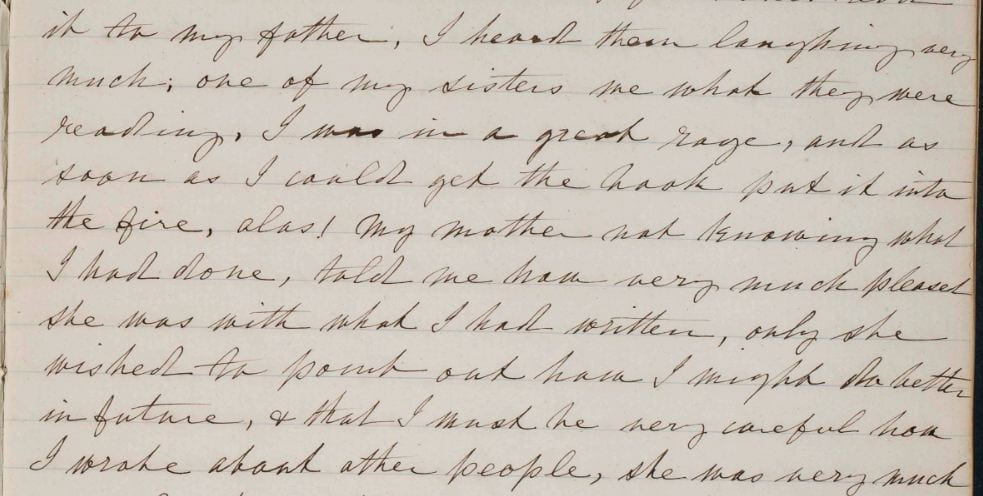

It was before the war, when we lived in the forest, I used to write down all I did, where I went, what people I met and what they said to me, sometimes I wrote the stories people told as we sat round the fire. One day my mother got hold of my diary. She went into her room & for hours read it to my father. I heard them laughing very much, one of my sisters told me what they were reading. I was in a great rage, and as soon as I could get the book put it into the fire, alas! My mother not knowing what I had done, told me how very pleased she was with what I had written, only she wished to point out how I might do better in future, & that I must be very careful how I wrote about other people. She was very much vexed when she found what I had done & also that I would not go on with the diary.

And now after all these years I commence again, just to trace if I can the fate of my latest work. (2 Aug 1885)

And so it is that we have an at times daily record of life and work at 34 Nile St 1885-86 and 1888-1890 in the form of two thick notebooks now in the Harris collection at Puke Ariki. These are the years when Emily sent paintings, decorative screens and table-tops to national and international exhibitions, as well as teaching with Frances and Ellen in the private school for local children run by the Harris sisters at Nile St. In January 1890 the diary shifts locale to Taranaki during the summer burn-offs and includes forays to Stratford, the lower slopes of Taranaki Mt Egmont and a close encounter with an out-of-control burn at Inglewood. Even during the Harris family’s time in the bush on Frankley Rd, New Plymouth, Emily realised that the relentless clearing of land for pasture and crops was wiping out precious native flora. In the 1890s her project to paint mountain flora was in part a gesture to document plants that were disappearing as farmland continued to encroach on fragile environments.

Emily’s second story about burning occurs in 1886 and involves her father Edwin, 80 years old and living with his daughters at Nile St:

I was hindered the other afternoon for an hour or more in a way I never dreamt of. Father brought a large tin downstairs & sitting down before the drawing room fire began putting papers & packets of letters in the fire. ‘What are you doing?’ I exclaimed. ‘Oh, I’m only burning old papers,’ he replied. ‘They are of no use’.’ I knew it would not be of the slightest use to remonstrate. I was aghast, for I knew that most of the letters [were] received for more than forty years by my dear mother & father, besides interesting papers of every possible sort. Mother had tied most of the letters up in little packets & written outside by whom they were written, most interesting letters I know, for most of them had been read aloud to all of us. How to save these to me most valuable documents & precious relics, I could not tell, but I popped myself down on the hearthrug. ‘Take care,’ said I, ‘you’ll set the chimney on fire,’ as the loose letters blazed furiously. ‘Oh, nonsense,’ said father, stuffing more papers in.

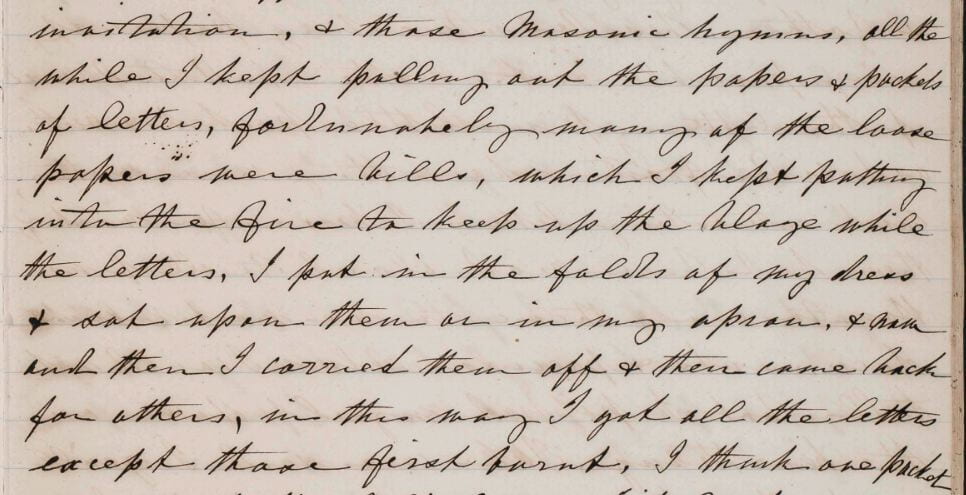

I was in despair, when a happy thought came to my aid. ‘Well don’t be in such a hurry,’ said I, ‘let me have the stamps for Hermann.’ (Mary had written a week before to ask me for some stamps for him.) ‘& look, see what you are putting in the fire, why, those are photos,’ & so making him look at the photos I got the scissors & saying, ‘Now just look at this & that & do cut off those stamps, & look at this invitation & those masonic hymns.’ All the while I kept pulling out the papers & packets of letters. Fortunately many of the loose papers were bills, which I kept putting into the fire to keep up the blaze while the letters I put in the folds of my dress & sat upon them or in my apron & then I carried them off & then came back for others. In this way, I got all the letters except those first burnt. I think one packet was Aunt Rendel’s letters.

It took several days before all the papers were burnt. There must have been hundreds but I looked well over them to see that nothing important was destroyed & father too picked out a good many. I think he must have thought that the tin contained only old bills & [papers] of that kind. I have been looking over the letters today: those relating to the first days of the settlement & the Maori War are deeply interesting & the longer they are kept the more valuable they will become. There are hundreds of letters, notes & papers. I must make a selection, some of them may well be destroyed but not in a wholesale fashion. (11 July 1886)

Over the coming summer we plan to prepare Emily’s diaries for online publication in the source materials section of our website, turning to the Nelson years of the Harris story when painting rather than writing was the focus of Emily’s attention. However, the diaries remind us that the Harris story proceeds on a deep layer of family memory that was tended to by several generations who kept its documentary record away from consuming flames. Emily again, writing about family friend and painting mentor Colonel Benjamin Aylett Branfill (1828-1899):

Col. Branfill told us the other evening that he had been spending his evenings lately in going over his diary, he wanted to write a short life of an uncle of his. He says he does not see why people who in private life have done their duty, have been of use to their friends or have been remarkable in their lives in any way, should not have their lives written, not for the public but for their friends & relatives. We told him that our mother had kept a book in which she had written down all she could recall from her father’s family. I am sure that most people in the Colonies should do the same, or how in a few years are their children to know anything about their English relatives if they have any. (2 Aug 1885)

Branfill’s archive was recently acquired by the University of Toronto Library. Sarah Harris’s family history was rediscovered along with a sketchbook by Edwin and an illustrated journal by Emily’s sister Frances when Goff and Judith Briant checked on family papers inherited from Goff’s father Hugh Godfrey Briant.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis