Michele and I are heading to Australia soon to check out hand-coloured sets of Emily Harris’s New Zealand Flowers, Berries and Ferns. In Sydney we’ll visit the Mitchell Library / State Library of New South Wales. Then we’ll continue on to Adelaide, where the University also has a complete, hand-coloured set of Flowers, Berries and Ferns. So far these are the only two coloured sets that we’ve managed to locate in Australia. We’re wondering if we’ll find Emily’s handwriting on the inside back covers, as Michele and Mark did at Kew Gardens Library in London earlier in the year.

New Zealand Flowers has been lifting off the page recently. After examining so many copies of Emily’s lithographs, I’m taking more notice of the springtime flowers. It started with kōwhai at the base of Maungawhau/Mt Eden. Then a couple of weeks ago I spotted kākābeak flowers on the Kelburn campus of Victoria University in Wellington. And before that Mark sighted them in Marlborough.

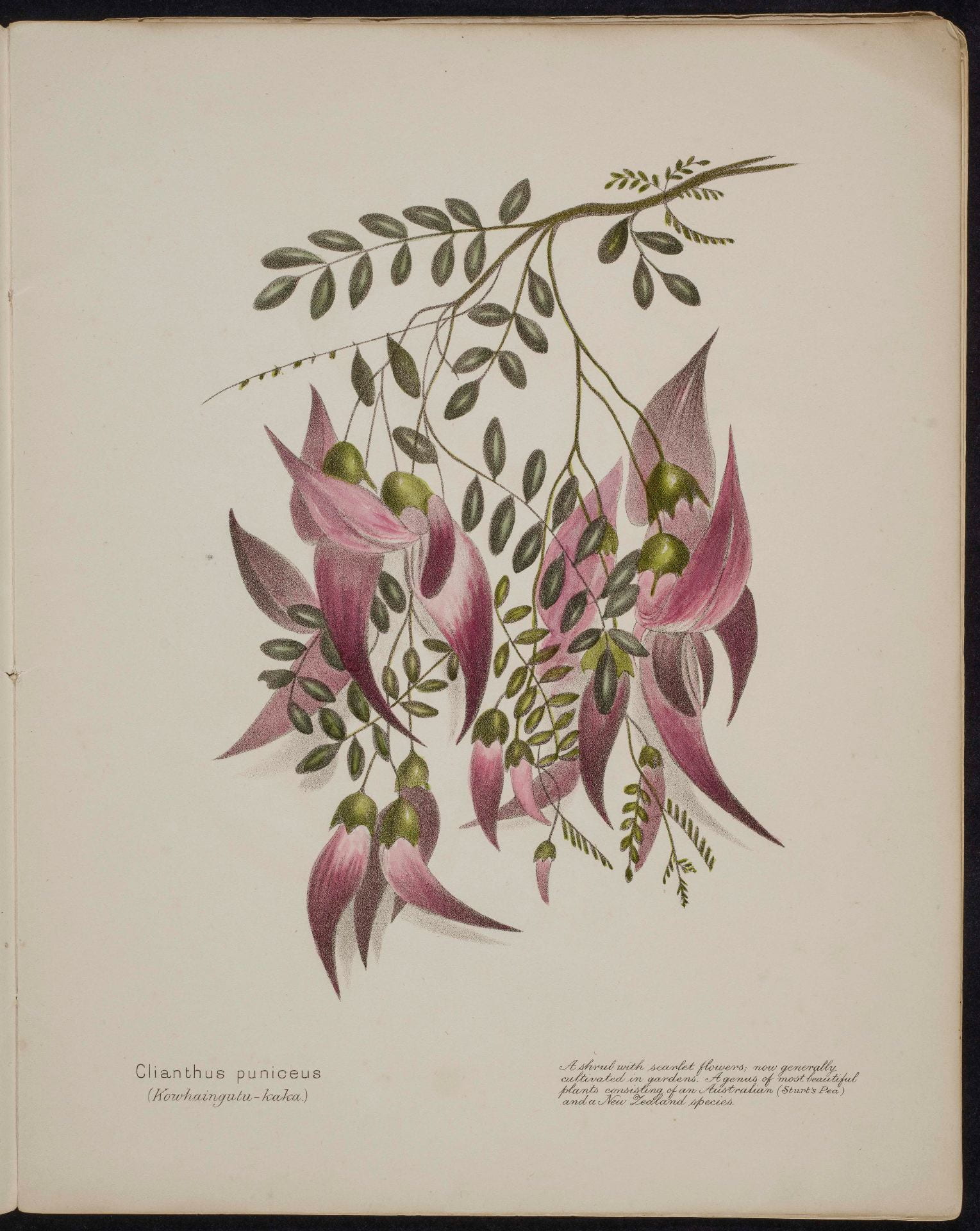

Which leads me to ask: should we assume that Emily painted her kākābeak in the first instance by observing a spring-blooming flower? It seems likely, given her insistence on drawing from life. And did she model subsequent colourings on a reference plate as orders for coloured sets came in between (as best we know) 1899 and 1910? It would be exciting indeed to locate her colour reference set of Flowers, Berries and Ferns. It’s been interesting to compare the different copies of New Zealand Flowers as we come across them. We’re not even sure that Emily herself painted them all. See, for example, the brush strokes of the Puke Ariki and Adelaide Clianthus below, one patchy, one boldly worked.

The ‘Clianthus puniceus (Kowhaingutu-kaka)’ plate is accompanied by Emily’s description: ‘A shrub with scarlet flowers; now generally cultivated in gardens. A genus of most beautiful plants consisting of an Australian (Sturt’s Pea) and a New Zealand species.’

Actually, kākābeak is only found in New Zealand. It has a close relative in Australia, but is otherwise unique. The two species found here are Clianthus puniceus, which Emily painted, and Clianthus maximus, which I suspect is what Mark and I photographed (comments from botany enthusiasts welcome!)

In Māori, ngutu means beak/lips and kākā is of course the native parrot. Emily includes the full name, kōwhai ngutukākā. Here is another flower whose name is associated with a bird. The kōwhai flowers are thought to have evolved to match the tūī’s beak. Ngutukākā is called ngutukākā because the flowers have the same shape as the beak of the native parrot.

According to the Department of Conservation, ngutukākā is ‘seriously threatened with extinction in the wild.’ It’s at ‘Nationally Critical’ status. That pulls both colonialism and the climate crisis into focus for a moment. Emily painting 130 years ago, kākābeak already more common in gardens than in the wild; pointing ahead to today’s threat of extinction. Introduced plants compete for sites to grow, and ngutukākā has no defence against introduced animals such as deer, goats, pigs, hares, or stock. Garden snails, introduced too, threaten these flowers. The DOC profile says that Māori used ngutukākā for gifting and trading, so the species could have been distributed around the country by passing hands.

We’ve already written about kākābeak in relation to first European contact. Back in June at the Natural History Museum, Michele and Mark saw Sydney Parkinson’s vividly-coloured 1769 drawings of a Clianthus in flower and one of the dried specimens that were brought to England by HMS Endeavour in 1770. To recap:

‘When botanist Daniel Solander went ashore 21 October 1769 at Anaura Bay in the East Cape district of the North Island of New Zealand, one of the first plants he collected was growing near the dwellings of the local people. The shrubs Solander saw were covered in clusters of bright red flowers and he named the plant Clianthus puniceus, recognising it as a member of the Fabiaceae or pea family. The Linnaean Latin means literally ‘blood red glory flower’ and tells us quite clearly about the impact of its blossoms on the newly-arrived Solander and his scientist boss Joseph Banks.’

There is another, even rarer variety of Clianthus that is not the ‘blood red glory flower.’ In 2015 ngutukākā made the news as the white-flowering version was brought back from the brink of extinction. The Crown research institute Scion was able to grow the white ngutukākā from a wild seed collector, and worked with iwi, DOC, Landcare Research, and the Ngutukākā Recovery Group to ensure its survival.

Project Leader Karen Te Kani says, ‘The white ngutukākā is considered precious taonga to East Coast iwi. About 100 plants have been gifted back to Ngati Kohatu and Ngati Hinehika iwi to be planted on their ancestral land.’

The return is significant:

Kiwa Hammond of Ngāti Kohatu and Ngāti Hinehika said, even though the white-flowered ngutukākā had not been seen for decades, its patterns were strong features in their carvings and ta moko.

The reason I was on the Kelburn campus in the first place was to visit an exhibition at the Adam Art Gallery | Te Pātaka Toi, Te Taniwha: The Manuscript of Ārikirangi (Ngā kupu whakamahuki nā Richard Niania, Photographs by Joyce Campbell). Te Kooti was from the East Coast. I noticed a dried white ngatukākā was displayed next to the chest that held his 19th Century notebook.

Back on the DOC species profile, I read that ‘Ngutukākā has a long-lived seed which may still be able to germinate after 30 years, creating a seed bank that holds many seeds ready to germinate when conditions suit.’ Maybe these seeds are a little like an archive, waiting for contact.

Lead writer: Betty Davis

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Michele Leggott

Tēnā koe Betty. A fabulous read, and looking forward to hearing more after your trip to Australia. Your pics are definitely Clianthus maximus, the Clianthus puniceus is a more of a salmon colour as in one of Emily’s illustrations. I’m as addicted to kākābeak as the tūī. So happy it’s becoming more well known in Aotearoa, loving this blog too.

Hi Rachael, great! Watch this space for more on Australia and Clianthus 🙂 And thanks for that plant ID.