Outside the hotel on Wentworth Avenue the temperature has hit 36 degrees. Sydney is burning: bushfires ring the city to north and west and an apocalyptic haze is turning the CBD sepia. We opt for a research day in our room and invite Sue Needham to come down with her big folders of Emily Harris material. We’ve looked at Dot Moore’s letter from Taranaki and now Sue is pulling out another faded fax. ‘I’d forgotten about this,’ she says. ‘It’s another letter from 1910, Emily writing to my grandfather Harry Moore. She’s giving him the family history.’ Like Dot’s letter, this one has been transcribed by Sue’s cousin Graeme Griffin, who faxed it to Sue when she was working on her Art History papers at the University of Queensland in 1996. Sue begins to read:

34, Nile Street East,

Nelson.

August 28, 1910

My dear Harry,

It seems just the right and proper thing that you being the eldest grandson should be the one to ask for the “Family History”. Although I do not know very much I probably know more than your mother or your Aunt Mary. I do not know further back than my grandfathers, James Harris and William Hill of Plymouth, England. My mother, your grandmother, wrote a short account for her children which I will copy first as it may refresh my memory. I have put in a few words of explanation here and there.

“A Brief Account of my Life for My dear Children”

“I have little of the merry days of childhood to record, which were as happy as health and the care of fond parents could make them.

At the age of twelve the first great sorrow came to us in the death of my dear mother and two elder sisters, my grandfather and two grand[mothers] within five years. I can well remember the delight we felt when the first white frock with a broad back ribbon tied behind was put on after being so many years in mourning.

(I find I began on a wrong page so will make a fresh start.)

Sue pauses while we whoop with excitement. Emily is copying from Sarah Harris’s notebook, rediscovered by Goff and Judy Briant among their family papers in Marton. It is Sarah’s notebook that allowed us to piece together the early part of the Harris story for The Family Songbook, which begins with the passage about the first white frocks and their black mourning sashes. Hearing Sarah’s words through Emily’s letter read by Sue is one of those truly uncanny experiences that mark archival research. Everyone seems present, literally on the same page. When we have calmed down, Sue reads on. Emily has found the right place in her mother’s notebook:

Biographical Sketches

of my own and my husband’s family the use of

my dear children in New Zealand.

I do not think it is necessary to go back father than our father’s family, that is your grandmother and grandfather. My grandfather was called Hill who married a miss Angel. My grandfather died before I was born, my grandmother lived until she was 92 years. My father her only son spent much money in endeavouring to prove her claim to the Angel Estate that had been in Chancery for many years, which I believe is not settled to this day, 1871. My father gave it up from not having sufficient means to carry it on.

My aunt, my father’s only sister, married a Mr Hugh Corbyn, a Purser in the Royal Navy. He died in service in the Mediterranean. His father, Dr Corbyn, practised in [stone]house, Devon, England.

My father, Mr William Hill, resided in Plymouth, Devon and married Miss Dyer, daughter of William Dyer who was independent. He was for many years afflicted with paralysis, he became speechless and unable to leave his room. His partiality for me was remarkable. I was removed from school to sit with him, read to him, give him his medicine and he used to say I was the only one of the family who understood him.

((note: I suppose he was able to speak a little. Your grandmother was about 12 when she had to attend on him)).

I remember going to walk one day and staying a long time for it was not [often?] I had that pleasure. When I returned I was told that he had been in a great rage at my staying, that he would not take his food nor let anyone do anything for him but kept ringing the bell and knocking with his stick. When I went to him he was quite glad and said, “don’t leave me again.” Poor grandfather, not many months after we were parted forever in this world. I was twelve years old then. His daughter, Elizabeth, my beloved mother, died three days after her father. I can remember well the great sorrow and mourning for those beloved ones both laying dead under the one roof.

Father never married again. Their children were:

1. Bessie, who died young

2. William

3. Eliza, died aged 21 years, one year after her beloved mother.

4. Emma Jane, died aged 64 (born 1802)

5. Caroline, died aged 19, two years after her mother.

6. Sarah, Mrs Edwin Harris, (N.Z.)

7. Ann Mountjoy, Mrs F. Paddan (London)

8. Roland, died at the age of three years.

By this point in Sue’s reading we have pulled up images of Sarah’s diary and Betty is following along, noting Emily’s regular departures from her mother’s script. Sarah now dives into detail:

Mr William Hill, father of the above children, died Sept 1846, aged 80 years and six months.

My brother William, your uncle, has long been a resident of France and for many years resided at St Quentin, now (1871) at [Nantes]. He has passed through three revolutions there, July 29 1830, 1848, and 1870, this last one the most dreadful ever recorded. The Communist revolution was put down May 1871. Your uncle is still living (1872) very old but remarkably well and writes a good letter, being between 70 and 80 years old.

William Hill married Miss Mary Ann Radmore of Plymouth, England. They had two sons, Victor born in France now residing in London (1871). ((I think they are wine merchants – E.C.H.)) Mrs William Hill your aunt died 1873.

Emma Jane Hill your aunt of whom you have heard so much lived in England.

She finished her education at Miss [L]inwood’s establishment, Hinchley, Leics, Mon. after which she went into partnership with Mrs Tickel and Miss Adams who had kept a boarding school successfully for fifty years.

Your aunt Emma as you have always called her, was the youngest partner and took the active part in the teaching having received a very liberal education. After my dear sister’s death which took place October 24, 1866, the school was given up.

We three younger ones, deprived of our elder sister’s care, grew up with a moderate share of good looks and good health.

Our brother William was at St Quentin, managing an establishment belonging to Mr Heathcote M.P. for Tiverton, Devon. He never returned to England as a resident.

Having outlined the lives of her brother and sisters, Sarah turns to her own history (and Emily begins compressing and editing in earnest as her concentration on the closely-written pages falters):

At 16 I visited Jersey where I spent five months on a visit to some old friends of my father’s. Jersey was then a charming place to visit – Jersey was at the time full of Spanish Refugees. There was much sociability balls parties visiting which I greatly enjoyed. Many years after my return, at an evening party given by my Aunt Corbyn I met for the first time Mrs Kendel, Miss Harris and their brother, Mr Edwin Harris. Miss Corbyn my uncle’s sister Miss Dalrymple a singer and harpist; there was plenty of music Edwin played the guitar and sang well. My voice was considered good at that time. This was our first introduction to the Harris[es]. My sisters Ann and Eliza were there also.

Two days after the party Miss Harris and her brother called on us in Flora Place where we lived and a great intimacy sprang up between the two families. Some months later I had an invitation to visit Ireland, I traveled from Devonshire through Wales over the [Menai] Bridge, crossed to Kinfstown stayed one day and night in Dublin and traveled by land to Cork, spent a week at the Lakes of Killarney returned home to be married after twelve months absence.

(I have had to leave out a good deal as I find it too much to write, and I must leave out the description of my mother’s wedding day, the guests, the party and her beautiful bride dress, her new home in Park Avenue, Plymouth.

It was considered a fairly good match as my father was doing well as a surveyor under his brother-in-law, Mr Kendel. E.C.H.)

For some years all went well we were happy and prosperous my three elder children were born, Hugh Corbyn, Emily and Catharine. My new home in Park Street, Plymouth was a small house containing I think 7 rooms back kitchen and garden. It was neatly furnished and I felt as the mistress of it one of the happiest women.

Catherine was born in Somersetshire Dulverton where we were two years during the survey made by Mr Harris for the Reform Bill your father had also been all through the country of Cornwall with Commissioner Dawson for the same purpose.

We were prospering and likely to do so but for a very unexpected troubles in a mill concern, which to oblige a brother-in-law of mine my husband to come surety. It quite ruined us.

At this time New Zealand was much talked of and Governor Hobson who was a friend of the Kendel’s wrote to them saying if Mrs Kendel’s brother would come to New Zealand he could find plenty of work in the survey for him.

I did not feel willing to go out. Edwin was bent on going and all his friends thought it a fine opening for him.

So there were great preparations made as the outfit and useful instruments for surveys and many useful and handsome presents from friends we might never see again. So at length all was ready and we left England for New Zealand.”

(I stop here as I find it too trying to copy out more of the narrative as is closely written in a small book.

I may later on write what I know of my Father’s life and his relations but he did not write an account of himself your Aunt Ellen and I used to ask him questions and then we made notes.

Emily Cumming Harris))

This is the bombshell moment. Our own peering at Sarah’s cross-written pages led us to believe that the trouble between Edwin Harris and his brother-in-law Frank Paddon was the consequence of difficulties over a will. Troubles in a mill concern in Plymouth in 1839 seem more plausible than troubles in a Will as a source of financial ruin. Even if Emily herself can’t read what is written beneath the pencilled overlays, she is likely to know about the circumstances that put her father briefly into debtor’s prison in Somerset in 1839 and propelled him into making the decision to emigrate to New Zealand in 1840 without capital and still in debt. Graeme Griffin’s meticulous transcription of Emily’s 1910 letter allows us to make one tiny emendation (an m for a w) and to add the words (‘to come surety’) to our transcript of the cross-writing.

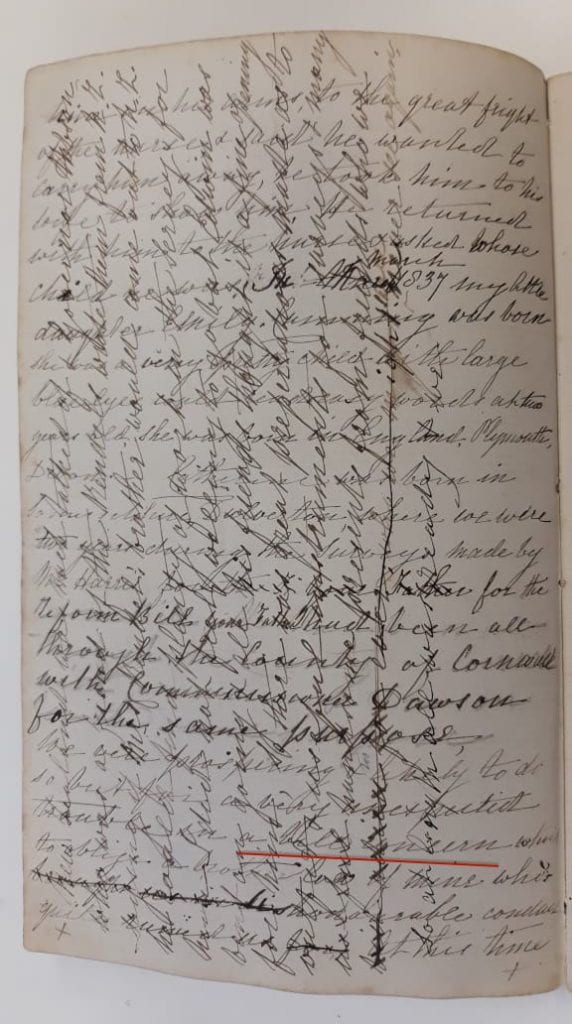

Trouble in a will or a mill? Sarah Harris notebook. Collection of Godfrey JW and Judith Briant.

One more question: what about Graeme’s transcription of Emily’s spelling of the name Rendel as Kendel? Since there is no doubt that Emily knew the eminent Rendel name, we must infer that her handwritten capital Rs make uncertain reading. The same thing happens in her 1880s diaries where the name of artist Ellis Rowan has been consistently transcribed as Mrs Carman. Our summer project to edit and publish the diaries involves page by page checking back to the handwritten notebooks to be sure of what Emily is writing. Kendels or Rendels, wills or mills; the day of fire has delivered another part of the jigsaw that is the Harris story. We leave the sanctuary of the hotel room and go out into the sticky half-light of Armageddon, Sydney-style.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis, Sue Needham