‘Dark Emily’ is a new poem from Michele Leggott, recently published in Poetry New Zealand Yearbook 2021 (which can be purchased at Massey University Press and other book retailers), and is available in text and as an audio performance by Michele on our website. For this blog post, I’d love to share a few of the traces of research I recognise among the lines of ‘ephemeris’ and ‘raven’s wing.’

James Upfill Wilson (1834-1878) is a mysterious figure in Emily’s diaries, her few existing mentions of him are filled with deep sadness. With research we have been able to piece together snippets of his life from stints working as a farmer in Collingwood or running a store provisioning gold diggers in Karamea to his death in the Nelson Asylum at age 44. He has been the subject of two previous blog posts: James Upfill Wilson and James Upfill Wilson Redux. And despite this searching and researching there is still much that we do not know around his relationship with Emily or about much of his life between the moments where he surfaces in records and PapersPast.

From Emily’s diaries, 22 November 1889

The next morning I went to call upon the Rev S. Poole, the examiner for the BA degree, to ask when I could have the room. He had just gone out but came back while I was talking to Mrs P.. He was in a great hurry to get to the schoolroom, so I went with him there explaining what I wanted as we went on. He is generally so full of compliments & jokes that it was rather a shock to me when he said, ‘Miss Harris you have allowed yourself to get so grey that I hardly know you — when I first met you your hair was as black as a raven’s wing.’

‘One cannot keep young forever,’ I said, & then we talked of other things. Yes my hair was dark enough then, but that was some eighteen summers ago, and Mr Poole never forgets that time – my visit to Motueka, where I met poor James – to my sorrow. That was so long ago, is it any wonder I am grey now? (22 Nov 1889)

I keep thinking about the concept of archival darkness, the dark spaces and voids in the archival record that are filled with unknowability. That James Upfill Wilson is a figure standing half in archival darkness and half in light. I can see some of the traces of him in ‘Dark Emily’ in enigmatic references that make me want me to point and exclaim in recognition.

A Name on Glass

ephemeris

three dark shapes | see how they got a T from the first initial

fly between ship and mountain | but see also how it could be a J

is this where it started | a name scratched

trail of tears | on a glass plate negative

nails of Christ | or the copy of a copy

my mother still bleeding | transfer of a backward writing hand

from the lost child | Immortelle

sister where are you gone | there can be two and one invisible

and the rough pillow wet | there can be two invisible

with everything left behind | until now

I stared at the vertical mountain | collapsing memory

willing it to lie down | someone calling out

and play with us | a brother or a younger one

three small bodies | look

in care | the scrawled name at the top of the photograph

three dark shapes | how they got a T from the first initial,

between ship and mountain | but see how it could be a J

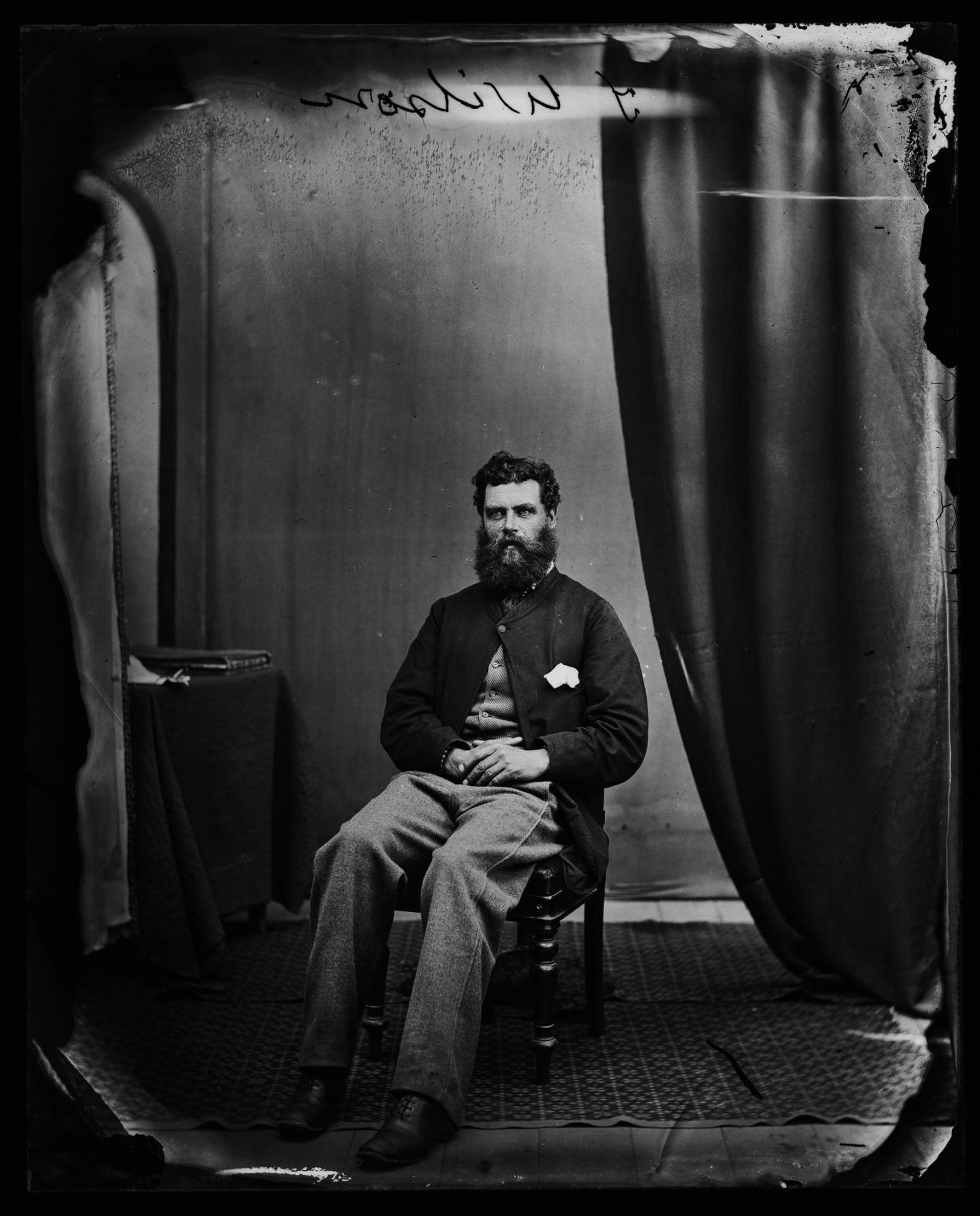

Below is the photo titled ‘Wilson, Mr A and T’:

‘James Upfill Wilson Redux’ goes into more detail over the various photos named ‘Wilson, Mr A and T’, featuring multiple different men (“a brother or a younger one?”) in the Nelson Provincial Museum, but this is the photo that we think is James Upfill Wilson because it is also featured in the Harris Family Album. Note the name scratched backwards on the glass plate negative at the top and the initial that was transcribed as a ‘T’ but could be a ‘J’. The poem takes these elements, some of them quoting and paraphrasing from the email discussions around the photos, and splits them across the lines of poetry capturing the obscurity of peering at those glass plate negatives as we tried to figure them out. The poem moves to and from these intertextual research moments and back again creating an enfolding of poetic imagining and research material.

The Curly-Headed Bellman

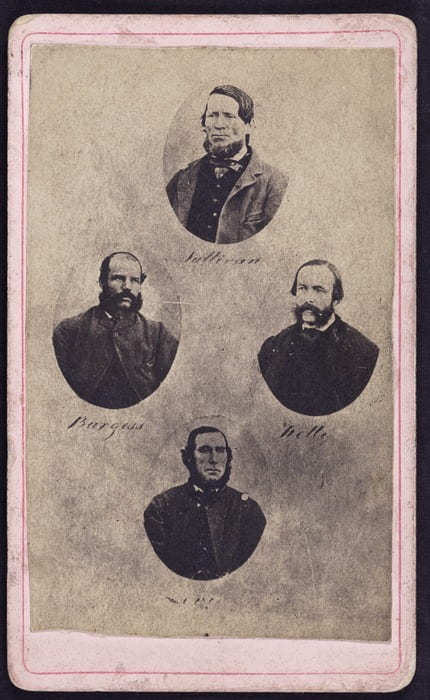

‘The curly-headed bellman’ was one of the possibilities we chased as we tried to trace James Upfill Wilson’s life before his death at 44 years. It turned out there was a James Wilson who worked as a bellman in Nelson which then earnt him the moniker of ‘the curly-headed bellman’ when he later associated with the infamous Burgess gang who committed the Maungatapu murders and was charged (and eventually acquitted) of the 1866 murder of George Dobson.

It appears, from the prisoner’s statement, that he has for years been the associate of bad characters, and in fact he admits that he has followed thieving as a profession for years. He admits that he was associated with Burgess, Kelly, Levy, and Sullivan, for the purpose of highway robbery, and that it was arranged between them that they should rob Fox on his road to the Grey.

That prior to the arrangements by the gang to rob Fox, Wilson had manufactured several masks to disguise the party, and after they were completed he took them up with him, together with other effects, met Sullivan and Kelly in the bush, and produced them for their inspection. When Sullivan saw the masks he asked Wilson what the he wanted with those things, or words to that effect, and Wilson answered him in slang terms ; Sullivan in reply let fall some observations which raised Wilson’s suspicions that it was the intention of the party to commit violence, and from that time he resolved to sever himself from the party — this was prior to the twenty-eighth day of May last, the day on which it is supposed poor Dobson was murdered. (Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, Volume XXV, Issue 134, 30 October 1866, Page 3)

We can see traces of this James Wilson and the crime in the poem ‘raven’s wing’ which dances around the identity of James Wilson:

raven’s wing

the world is wide | the Lord Worsley for Sydney

and he is in it somewhere | the curly-headed bellman

black as a raven’s wing | working his passage

watching the flight | was this him

of the bodies of light | was this not him

he might take you | a cold wind down the Grey

for the young May moon my dear | following a profession of thieving

a fiddle and a dancing step | is this him

and there you are | is this not him

the young May moon | curls plastered down

black as a raven’s wing | bringing masks and disguises

bodies of light | to the camp in the bush

watching the flight | an accomplice

in Morna’s grove my dear | but not a murderer

the world is wide | could be

and he is in it somewhere | couldn’t be

‘Black as a raven’s wing’ quotes Rev. S. Poole describing Emily’s hair (“when I first met you your hair was as black as a raven’s wing”) creating an echo of Emily, of youth and of Emily’s youth even as it is used to describe the curly-headed bellman. The fragment ‘a cold wind down the Grey’ references the title of Wendy M. Wilson’s A Cold Wind Down the Grey: Based on a True Crime Story which retells the story of The Burgess Gang from the perspective of Inspector James and who helped weigh in if James Wilson might be James Upfill Wilson. The consensus was that it was very unlikely but even the thought of possibility, however unlikely, is captivating and the oscillation between ‘was this him’ ‘was this not him’ ‘is this him’ ‘is this not him’ ‘could be’ ‘couldn’t be’ captures some of that feeling of tracing down James Wilson with bated breath.

The rest of ‘Dark Emily’ can be read here.

Lead writer: Brianna Vincent

Research Support: Michele Leggott, Dasha Zapisetskaya, Wendy M. Wilson (past).