By Michele Leggott

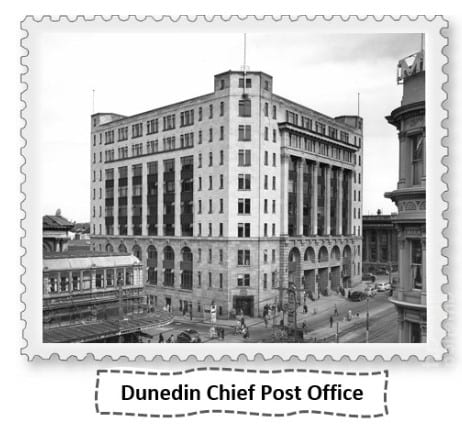

There is pomp and ceremony, and there is a lot of art. Almost 1150 works hang in the Post Office building in Dunedin, which has been repurposed by an energetic committee of gentlemen as the location of the first Fine Arts exhibition in New Zealand. Honourable Secretary William Hodgkins delivers the committee’s report 12 February 1869 to a splendid attendance of citizens and local dignitaries. He explains that the committee convened five months previously in September 1868 and resolved to invite artists from Dunedin and other parts of the colony to contribute works for exhibition. The loan of paintings in the possession of Dunedin families was solicited, and the range of exhibits was extended to include chromolithographs, architectural drawings and photographs. Otago Superintendent James Macandrew, standing in for Governor Bowen, gives an opening address that includes his hope that the exhibition will inspire the young artists of Dunedin and lay the foundations for a public art gallery in the city. There are motions of congratulation, applause and cheers for the committee. Then the crowd pushes towards the artworks on the walls or to the refreshment room, the approach to which is also hung several layers deep with paintings. The newspaper reviewer takes out his notebook and begins at the left side of the entrance, working his way around the hall and scrutinising each exhibit. He does not hold back on aesthetic or technical critique.

No. 1 on the catalogue is a painting by a local artist, Mr J T. Thomson, of a piece of New Zealand rock scenery, Fording the Roaring Meg. Truth compels us to say that, although the artistic powers of this gentleman are undoubtedly great, and that although he presents an excellent drawing of the scene he reproduces, this picture, in common with the numerous others from his fertile pencil, is disfigured by a violence of colouring for which no skill in drawing can compensate. The manipulation is excellent, the light and shade of the slaty rocks standing out boldly from the sides of the hillside admirable, but the decided and brilliant purple used is totally unlike anything in nature, and is a colour which no amount of glazing, or toning even, can kill, and which materially detracts from the value of an otherwise good picture. (Otago Daily Times 15 Feb 1869: 2)

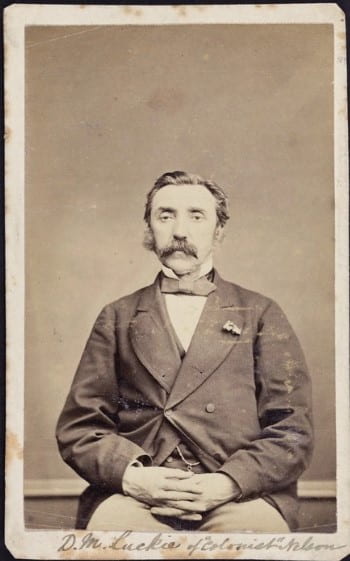

A week later in Nelson, editor and part-owner of the Colonist David Luckie peruses the extended review of the exhibition in Dunedin. A Scot himself, he chuckles over the sharp observations of the Otago Daily Times reviewer. Nelson artist John Gully has fared well: ‘Passing into the water-colour room to the left, we have some very beautiful sketches by Barraud, sent in by Mr E B. Cargill ; and then comes Gully’s Mount Cook painted, as we are told, from the Waikohai Point. It is in his best style, and comes near to being one of his best works.’ But Luckie is looking for another Nelson name among the watercolourists, and when he does not find it, he takes a fresh sheet of copy paper and begins to write, consulting notes made a few weeks earlier:

Water Color Paintings. Flowers and Fruits. — Some very creditable specimens of this branch of art have been executed by the daughters of Mr. E. Harris, artist, Nile-Street, Nelson, and transmitted to Otago for exhibition there. The largest work is by Miss Harris, and is devoted to native flowers. In this picture pink and white convolvoli, native clematis, and koromiko are prettily interspersed with their various foilage [sic], and vividly green ferns, furnish a bright foil to the delicate tints of their superior companions ; flax blossoms and supplejack berries are artistically thrown in for darker tints, and the whole work is nicely grouped. The second picture is by the same lady and represents the beautiful magnolia, the tiger iris, cloth of gold rose, dahlia, moss rose, kowhai (Edwardsia microphylla), miguonette, &c. It is rich in color but inferior to the first in composition. The third picture is contributed by Miss Frances Harris, and is a very creditably painted fruit piece, the peaches being very well executed, while the various fruity adjuncts, and the rata blossom peeping out of the basket in the background make up a pleasant picture. We hope to have the opportunity of viewing some further productions of the pencils of these ladies at an early future. (Colonist 23 Feb 1869: 2)

And this is how we know that Emily and Frances Harris sent work to the Otago Fine Arts Exhibition. The invitation may have come from William Hodgkins, at the instigation of John Gully, who was a friend and neighbour of the Harris family. Neither Emily nor Frances appears in the hastily-assembled Dunedin catalogue, and we have only Luckie’s description of their work to indicate its composition and effect. Fortunately David Luckie had a keen eye for both, and in Emily’s case a knowledge of botany and horticulture that produced a vivid representation of two different kinds of flower painting. Frances has merged her still life of fruit with a basket of scarlet rātā. Emily has made one work that focuses on native flora and a second that brings together garden flowers plus a sprig of kōwhai. One picture features flowers, ferns and berries; the other mostly gold-toned garden flowers in what will become Emily’s signature composition: the arrangement of multiple plants pleasingly grouped by shape and colour. David Luckie prefers the balance of her native flora, pinks and whites set against the vivid green of ferns and the red of flax flowers and supplejack berries. But he is almost as admiring of the yellows and golds of the garden flowers, so detailed in his naming of them that we hear the gardener’s voice and wonder where Emily got her specimens.

David Luckie knows where these flowers came from. His list is a graceful nod to the Nelson gardener, or gardeners, who grew them and who (along with Emily Harris) will be reading his column. John and Jane Gully, both excellent gardeners, will appreciate Luckie’s specificity as well as his promotion of the two young Nelson artists. Luckie, who is a stringer for the Otago Daily Times and its sister publication the Otago Witness, decides to give the Harris sisters an extra plug in his next round-up of Nelson news, quoting himself:

Nelson (From Our Own Correspondent). February 28th. […] Some very creditable pictures of native flowers have been sent to the Otago Exhibition, by the daughters of Mr Harris, artist, Nile street. They have been very highly spoken of by the Press here. (Otago Daily Times 9 Mar 1869: 3. Rpt Otago Witness 13 Mar 1869: 7)

The watercolours themselves have disappeared, making David Luckie’s descriptions all the more important and confirming that Emily Harris was not solely a painter of native flowers. In 1882 she was painting garden flowers on decorative works exhibited at the New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch. The source of at least one flower was clarified in a Nelson review:

We were recently favoured with an opportunity of inspecting some exceedingly pretty and novel water colour paintings which Miss Harris has for some time past been engaged upon with a view of sending them to the Christchurch Exhibition. Those of this lady’s paintings which have hitherto attracted the most favorable notice have been of New Zealand flowers, which she has been thoroughly successful in representing with the utmost faithfulness. On the present occasion, however, she has preferred the garden flowers, and those that see the result of her labors will at once admit that she is quite as much at home with the imported as she has proved herself to be with the native blossoms. The paintings are on black satin, and are intended for a table cover, two hand screens, a bracket, and a mantelpiece border, and although the flowers are different, the same idea has been carried out in each, the centre being a beautiful cluster, consisting principally of geraniums, pansies, lilies, and other well known flowers, while the border is of white clematis, and pendent at the corners of the table cover and the centre of the brackets are magnificent white and red fuchsias that on the mantelpiece bracket being of so enormous a size as almost to give the impression that it is exaggerated, but Miss Harris assures us that it is an exact copy of a splendid blossom grown by Mr S. B. White in his greenhouse. (Nelson Evening Mail 16 Mar 1882: 2)

Stephen Brown White and his wife Emma were friends and neighbours living nearby in Shelbourne St, mentioned several times in Emily’s diaries 1885-91. David Luckie left Nelson in 1873 to become editor of the Daily Southern Cross and the New Zealand Herald in Auckland, and later the Evening Post in Wellington. From 1879 he was Commissioner of the Government Insurance Department in Wellington. Emily did not forget his early support of her work. Years later in Wellington, preparing for one of the family exhibitions, she refers several times to David Luckie and his wife Fanny:

Thursday. Stayed in all day until five, then called to see Mrs Percy Smith. After tea went with Mrs Lee to see Mr & Mrs Luckie.

Friday. Went to see the room in the morning. Mr H. Baker took me to see the Press Editor, also the Evening Post Editor, & put in adts. Invited Press Editor to inspect pictures at 3 p.m. Monday, Post Ed. in the morning. Dined at the Luckies’. Mr Luckie went with me to the Times Office. In the afternoon went with Mrs Luckie to call on Mrs Chantry Harris. (Diary, 9-10 Oct 1890)

Mrs Lee is John and Jane Gully’s daughter Fanny. Emily is staying with Fanny, her husband Robert Lee and their children in Tinakori Rd, Thorndon. The Lees and the Luckies help with the exhibition at Baker Brothers auction mart on Lambton Quay before and after it opens 14 October. Emily reports to Frances and Ellen in Nelson: ‘Mrs Lee & Mrs Luckie have been so kind in staying with me at the room.’ (Diary, 15 Oct 1890)

The Otago Fine Arts Exhibition of 1869 is as far as we know Emily and Frances Harris’s first public appearance as watercolourists. The exhibition ran for much longer than its scheduled month, closing after 50 days of record attendances. Not long after the doors closed for the last time, William and Rachel Hodgkins’ third child and second daughter Frances Mary was born 28 April 1869. Superintendent Macandrew, looking to the future of art in the colony, had wished upon a powerful star.

As always, I am overwhelmed by your research skills, and your dedication. Thanks,Suezig gully