By Michele Leggott and Catherine Field-Dodgson, with research support from Runa Bhakta and Libby Baker

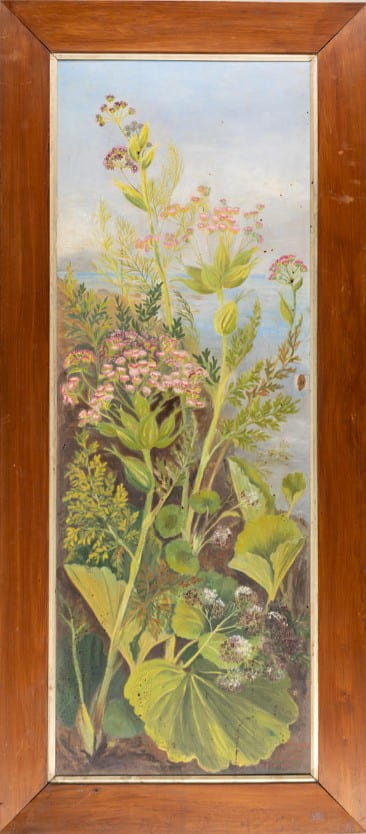

Four tall spikes of ligusticum reach from the bottom of a rectangular panel towards the top of Emily Harris’s painting. The two largest have flower heads that resemble a carrot in flower, but with pink rather than white umbels and there is another smaller pink spike on the right of the panel. The leaves are feathery and luxuriant. The fourth spike has smaller purple flowers and almost touches the top edge of the panel. At the bottom of the composition is an aralia plant, with large round leaves shaped like a giant geranium. The aralia also has sprigs of little purple and white-coloured flowers. Brown background hues give way to blues and greys half-way up the panel, suggesting the plants are growing on a cliff overlooking the sea. Above the horizon line the tops of the ligusticum spikes stand out against a pale blue sky. The panel is a striking scene of sub-antarctic plants pictured in their natural habitat.

These are big plants, mega-herb that Emily is representing near life-size. Frederick Chapman wrote of the plants he encountered at Adams Island in January 1890: ‘Near the shore the Ligusticums, L. latifolium and L. antipodum, grow in splendid profusion, their stout rhizomes and huge rigid leaves stopping the progress of pedestrians.’

Two days later at Campbell Island he was even more impressed: ‘The size of the Ligusticum latifolium of several varieties was amazing.’ (Transactions Vol 23 1890: 505, 515) And the aralia? Some days earlier at the Snares Chapman had commented: ‘Perhaps the most striking plant on the island is Aralia lyallii, or an allied species, which here grows to an immense size, and seems to do equally well under the trees or in the open, the rich guano soil evidently suiting it. Its leaves are sometimes 28in. in diameter, possibly even more. They stand 4ft. high, on stout rhizomes, and form, with the whitish-green masses of flowers and waxy seeds which rise in huge bunches from the centre of the plant, a very attractive object. (Transactions Vol 23 1890: 494) At 1037 x 601mm (4 and a half feet by almost 2 feet) Emily’s panel appears to be purpose-built for accommodating examples of each species.

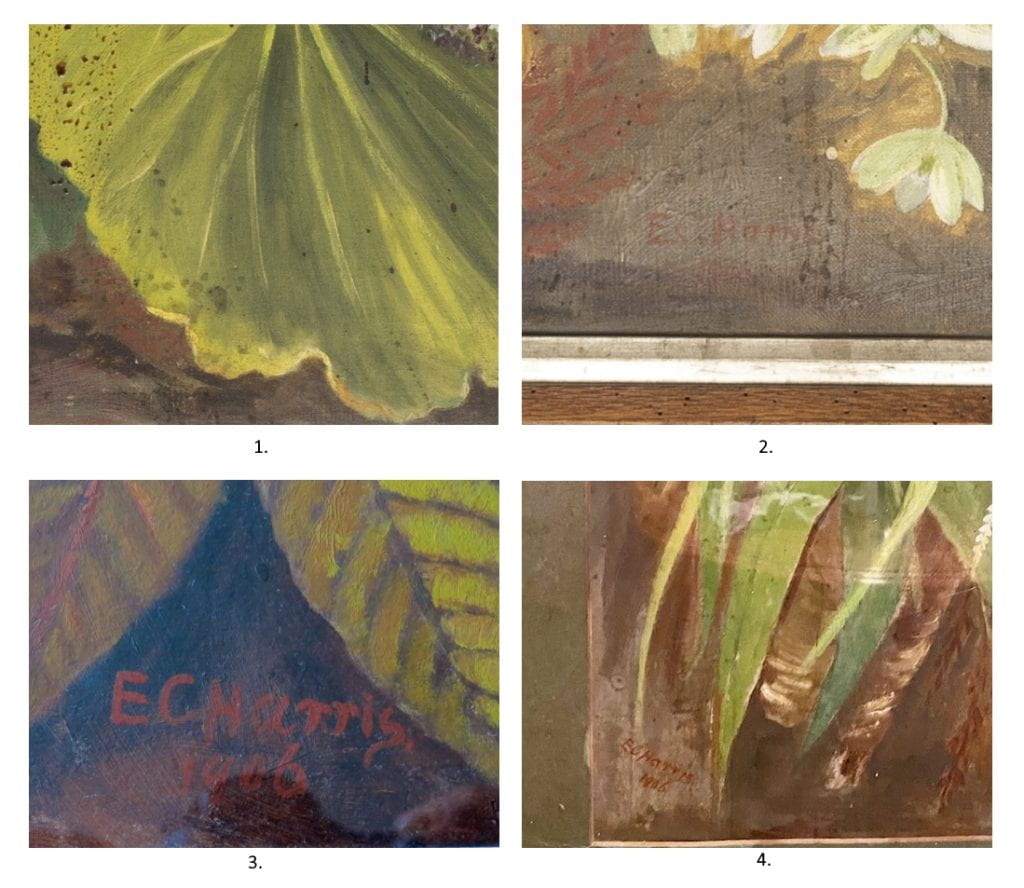

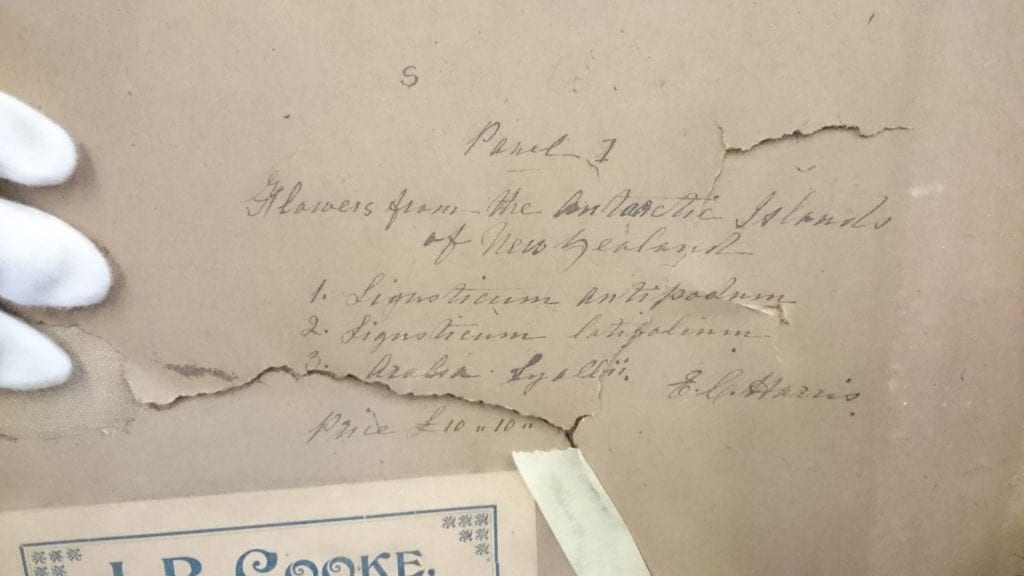

Co-opting pictorial collections curator Runa Bhakta and Taranaki friend Libby Baker, we set out to look closely at Emily’s two 1906 panels at Puke Ariki in New Plymouth. First Runa and Libby located and photographed the signature and date near the bottom edge of each panel. As expected both are in red oil paint, date below signature, no punctuation after initials, bringing them into line with Emily’s other 1906 works.

1. Antarctic Flowers

2. New Zealand Clematis

3. Mānuka and pōhutukawa

4. Kiekie, nīkau et al

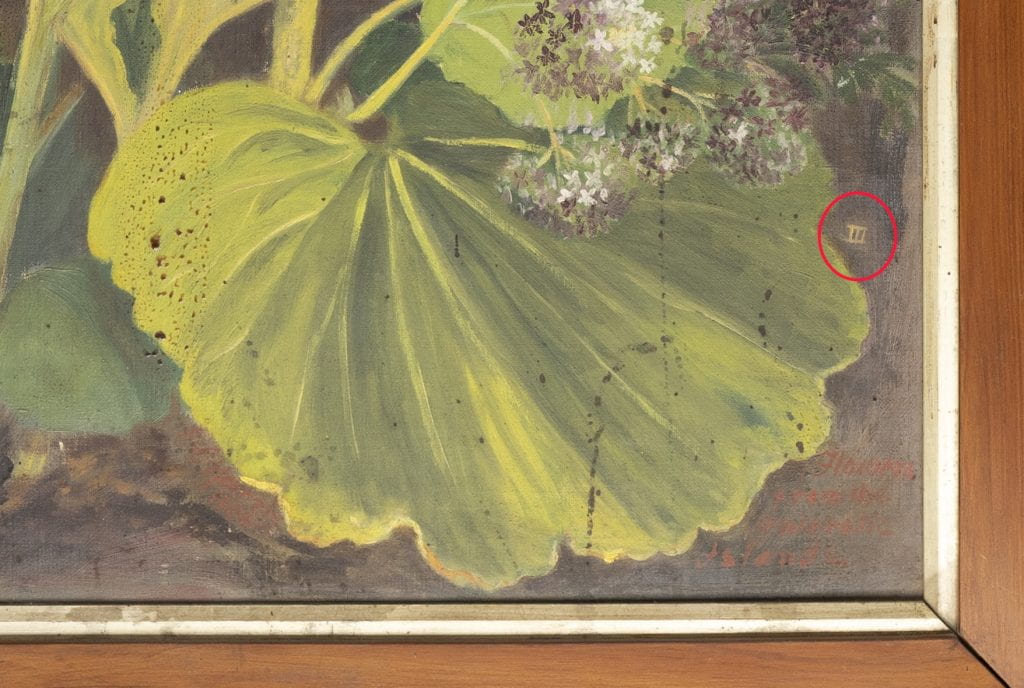

The clematis panel at Puke Ariki carries only signature and date but there is more to see on the Antarctic flowers work. To the right of Emily’s signature, barely visible against the dark brown earth, is a title, also in red: ‘Flowers / from the / Antarctic Islands’ and above it a pale roman numeral III.

On the back of the panel the artist has provided more detail about her painting:

Panel 1

Flowers from the Antarctic Islands of New Zealand

1. Ligusticum antipodium

2. Ligusticum latifolium

3. Aralia Lyalli

E C Harris

Price £10-10.

Emily wants ten guineas for the panel which she is sending to the 1906 International Exhibition in Christchurch as one of more than a dozen paintings forwarded by members of the Nelson Suter Art Society. The panel is a large and important work and Emily has been careful to identify each species she has painted.

Turning again to the front of the panel we ponder the significance of the numeral that floats above the title. Three flowers? Yes, but why the mysterious III? Catherine pores over the high resolution image Runa has sent through, zooming in close to look for numerals I and II. And there they are, almost illegible, one against dark ground, the other against the light ground of the upper part of the panel. Each is positioned below the flower it designates and angled slightly to echo the curve of a nearby stem. I is the pink Ligusticum antipodum (Emily has mis-spelled the species name), II is the purple Ligusticum latifolium and III is the purple Aralia lyallii.

We are feeling rather pleased with ourselves when Libby and Catherine point out another number on the panel, this time black on brown, a 16 above the III on the right of the painting. How did we miss this and what does it signify? Why didn’t the Puke Ariki cataloguers pick up the numerals or the stray 16?

The answer to these questions gives us pause for thought. The 1906 panels have been at Puke Ariki, formerly the Taranaki Museum, since 1925 when they were donated by Emily’s sister Mary Weyergang after the artist’s death in Nelson that year. Over time the surface of each panel has darkened with accumulated dust and the chemical changes wrought by ageing varnish. More distressingly, it seems that the 16 that shows up in our high resolution image isn’t part of the painting but something lying behind a small hole in the picture surface, a ghostly addition that will disappear when the panel is cleaned and restored. We ask Runa to put in a conservation request for both panels and settle down to wait for the return of Emily’s colours to something like their original appearance. What will the remediation of the effects of 113 years spent first at Nile St, Nelson, and then at the museum store look like?

Meanwhile we can make some guesses about the size and content of Emily’s second panel of Antarctic flowers, to date unlocated. Given her predilection for symmetry we can guess the second panel will be the same size and shape as the first. Given also that Emily painted six species of Sub-antarctic mega-herbs, we might guess that three more appear in the second panel. Given the numerals of panel 1, we might guess that panel 2 will carry numerals IV, V and VI as identifiers of the species depicted.

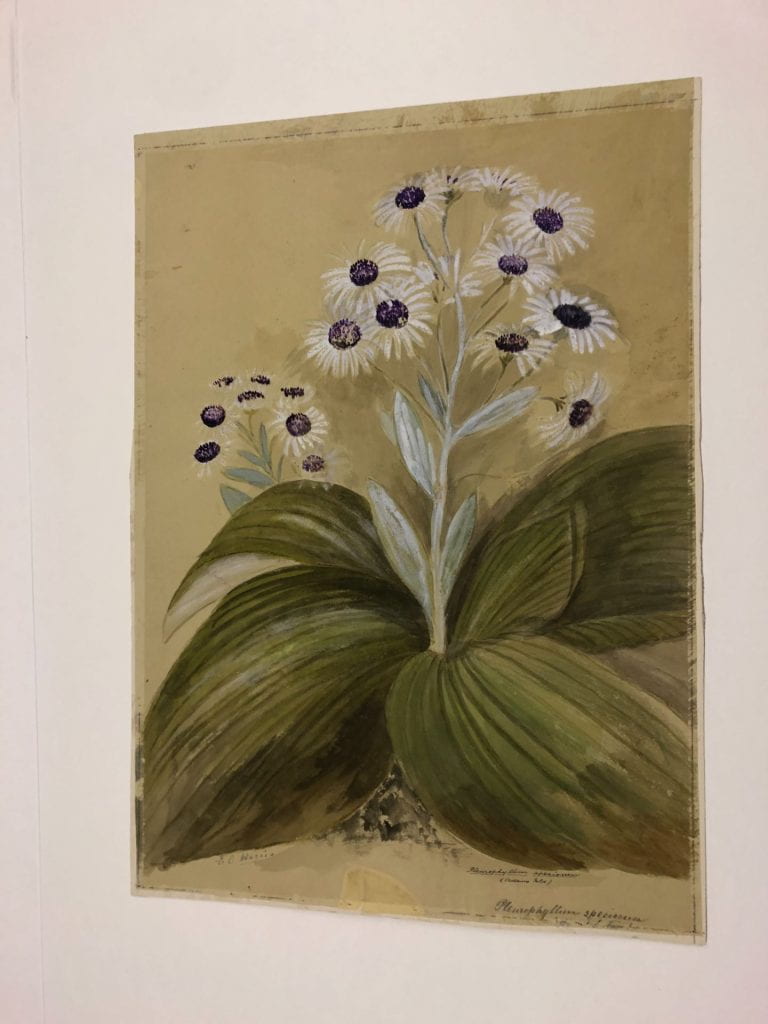

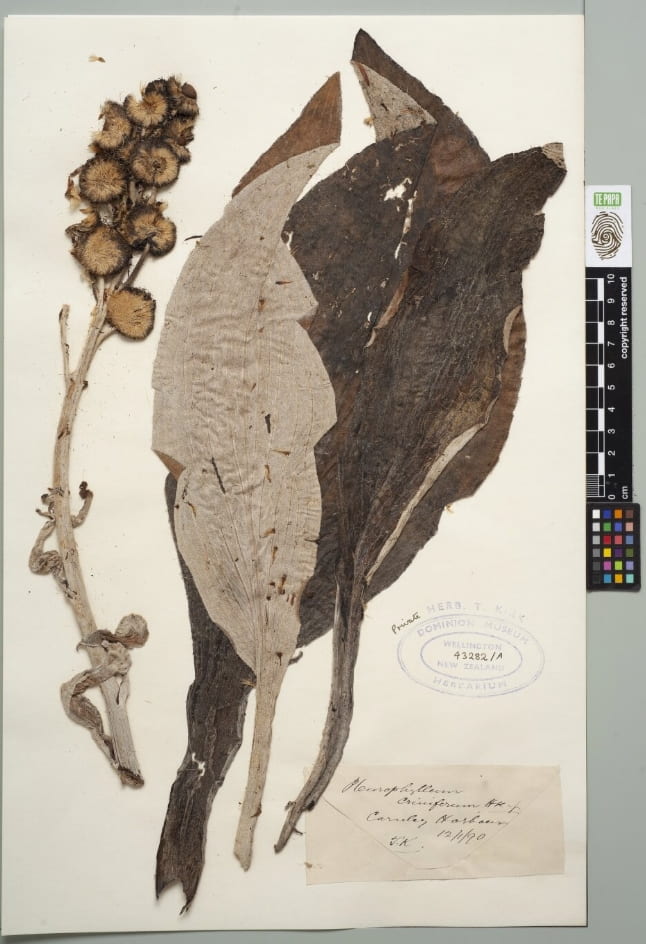

The case for these speculations becomes stronger as we check on likely plants in Emily’s paintings and in Thomas Kirk’s herbarium at Te Papa for the specimens from which they derive. Two pleurophyllums and a bulbinella become the focus of our enquiry, suggesting a panel of purples and golds against a rocky coast. Chapman again, at Carnley Harbour on Adams Island: ‘Over the whole country Pleurophyllum speciosum sends up, amid huge ribbed leaves, 2ft. long, its spikes of beautiful lilac or purple flowers. […] The next species, Pleurophyllum criniferum, was also plentiful. Its leaves are even larger, and, though not so handsome, make it a very fine plant, especially as its tall, white flower-stalk, sometimes 3ft. high, covered with button-like, brown, rayless flower-heads, 1in. across, is a very striking object.’

And at Campbell Island: ‘Here the Pleurophyllum speciosum was in better season, and the flowers were of a much deeper purple than those we had seen before. From being isolated the plants had grown better, and each was a picture in itself.’ (Transactions Vol 23 1890: 506, 513)

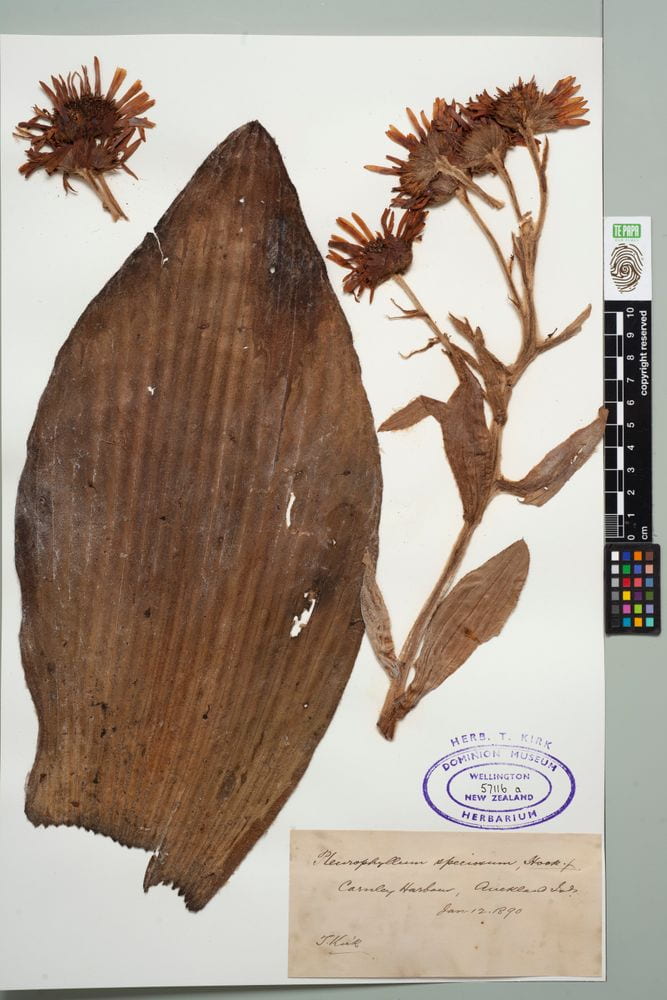

Collected by: Thomas Kirk FLS, 12 Jan 1890

Location collected: New Zealand, Auckland Isds [Islands].

Handwritten label: ‘Pleurophyllum speciosum, Hook. f / Carnley Harbour, Auckland Isds, / Jan 12. 1890 / T. Kirk’

Registration Number: SP57116a

Credit line: 2022-2023

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Collected by: Thomas Kirk FLS, 1890-01-12

Location collected: New Zealand, Carnley Harbour

Handwritten label: Pleurophyllum / criniferum Hk .f / Carnley Harbour / 12/1/90 / T.K.

Registration Number: SP043282/A

Credit line: 2022-2023

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

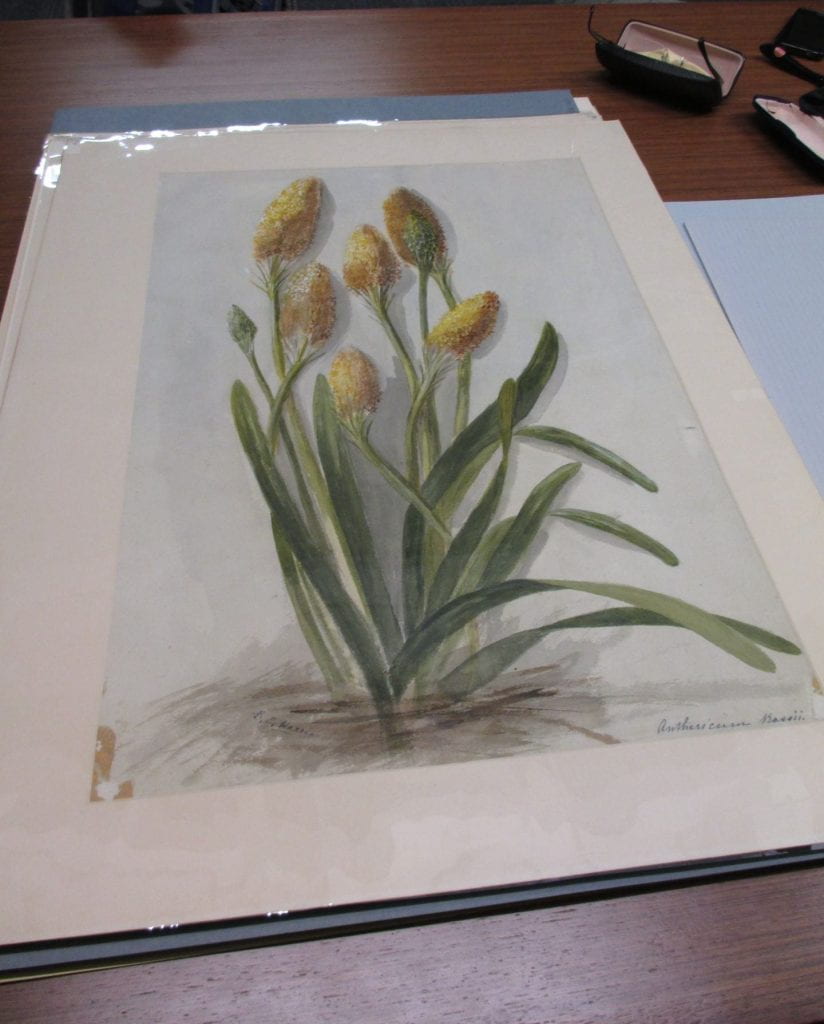

There are also specimens that match Emily’s depictions of Anthericum rossii (later Bulbinella rossii). The plant was admired by Chapman at Campbell Island in 1890: ‘’Here, too, we found in flower the beautiful golden lily called Anthericum rossii.’ (Transactions Vol 23 1890: 514).

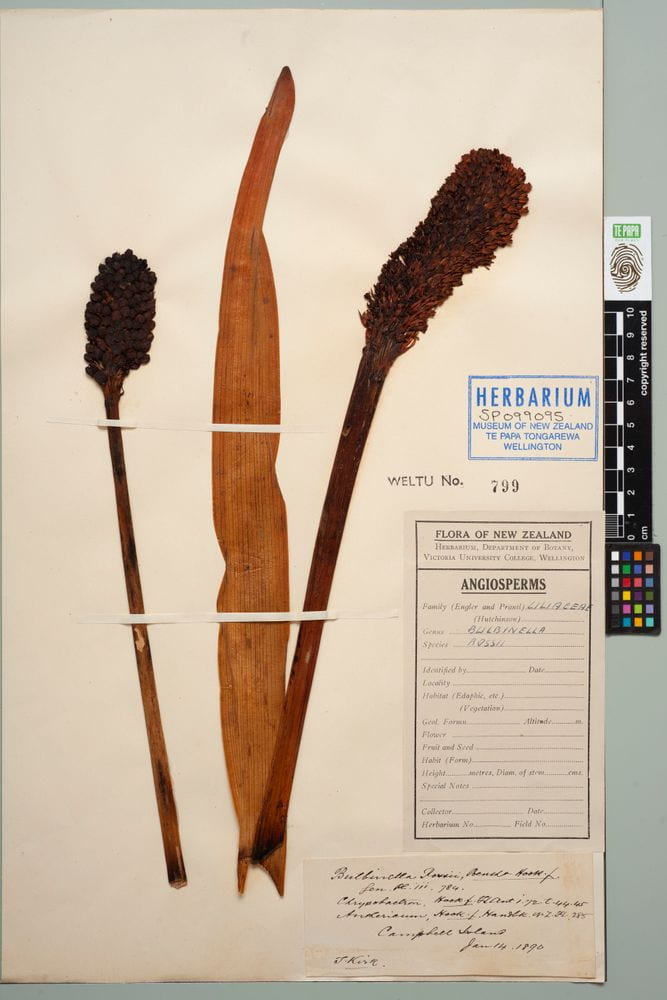

Collected by Thomas Kirk FLS, 1890-01-14.

Location collected New Zealand, Campbell Island.

Kirk’s label ‘Bulbinella Rossii, Benth + Hook / Gen. Pl. iii . 784. / Chrysobactron, Hook f. Fl Aust i. 72 .t.44.45 / Anthericum, Hook f Handbk . N.Z. Fl. 285 / Campbell Island / Jan 14 1890 / T. Kirk.’

Registration Number: SP099095

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Pinks and purples for panel 1, and perhaps purples and golds for panel 2? But of course Emily could surprise us if the second panel reappears.

There is one more consideration to be made about Puke Ariki’s ‘Flowers from the Antarctic Islands.’ It concerns the discrepancy between Emily’s colouring of her Aralia lyallii (now known as Azorella lyallii) and what the botanists have to say about the plant. The sub-antarctic species is Aralia lyallii var. robusta and it invariably produces dull yellow or whiteish-green flowers. (Kirk, Transactions Vol 23 1890: 429; Chapman, Transactions Vol 23 1890: 494) But Emily Harris makes her aralia flowers purple and therefore seem to be depicting the mainland species Aralia lyallii:

Emily prided herself on her meticulous rendition of botanical detail. Did Kirk, who most likely supplied her with specimens, mix up his varieties or location, or did Emily? She would not be pleased to discover that the aralia in her Turnbull watercolour and 1906 panel is not a sub-antarctic variety. The question of the sub-antarctic aralia colouring remains a small but significant problem in the work.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks again to Bridget Hatton and Dr Heidi Meudt of the Botany Department at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongareawa, and Alex Fergus from Landcare Research, for their help with locating herbarium specimens and identification of sub-antarctic flora.