Section 1: August 1885

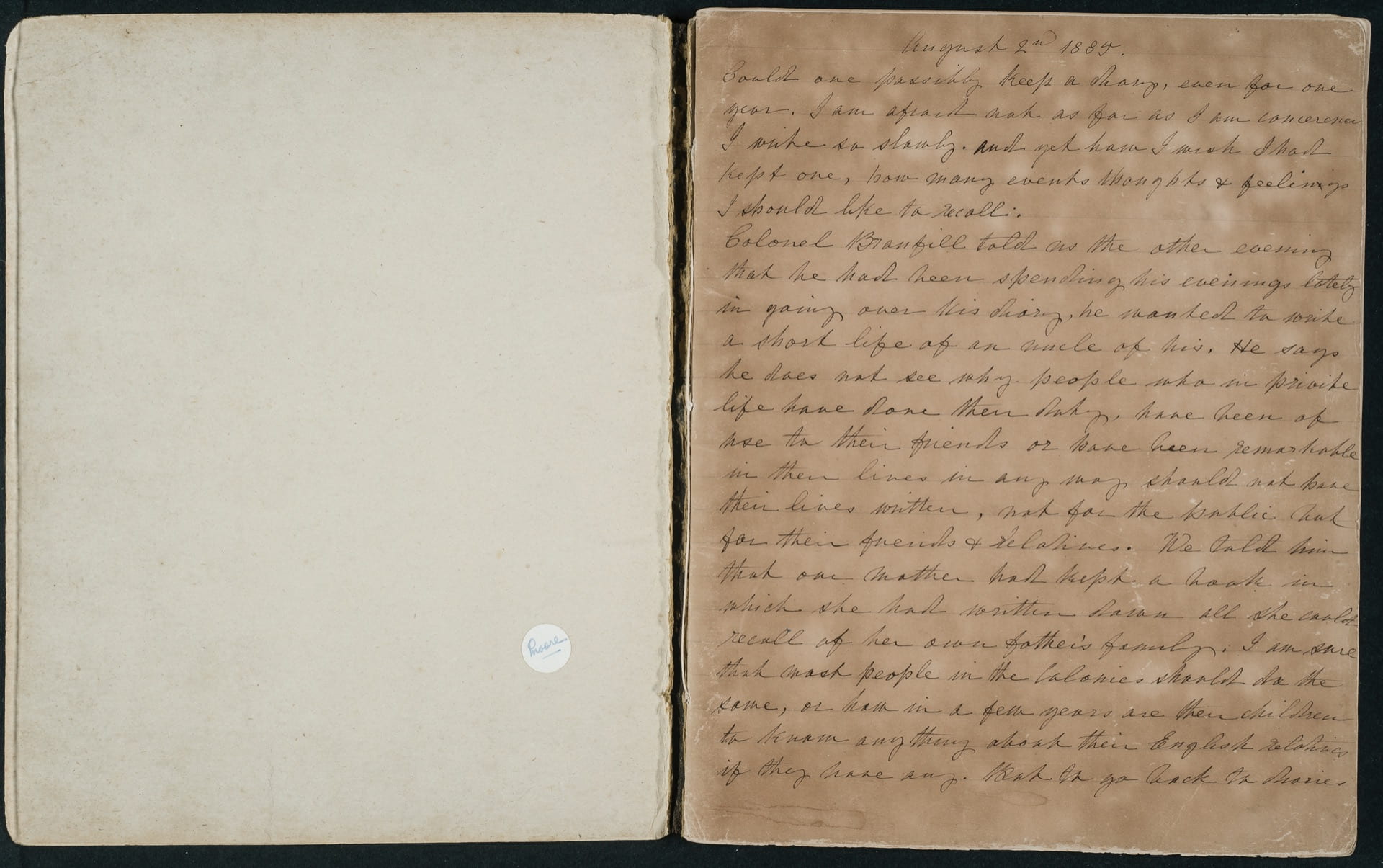

August 2nd 1885 [Sunday].

Could one possibly keep a diary, even for one year. I am afraid not as far as I am concerned. I write so slowly and yet how I wish I had kept one, how many events thoughts and feelings I should like to recall.

Colonel Branfill told us the other evening that he had been spending his evenings lately in going over his diary. He wanted to write a short life of an uncle of his. He says he does not see why people who in private life have done their duty, have been of use to their friends or have been remarkable in their lives in any way should not have their lives written, not for the public but for their friends & relatives. We told him that our mother had kept a book in which she had written down all she could recall from her father’s family. I am sure that most people in the Colonies should do the same, or how in a few years are their children to know anything about their English relatives if they have any. But to go back to diaries. What an eventful one Colonel Branfill’s must be, an English gentleman with an old estate although small and impoverished now, an Indian officer, at present an artist and teacher of drawing.

Well, long ago, some seven & twenty years, in the days of my youth, what an age ago! And yet now I seem to be just beginning to find out what I can do, & how to do it. If I could only have had the advantages then that young people have now, instead of groping in the dark & longing for what we know not, what a different career would have been mine. Oh that diary, begun when I was young and life was all before me. I wish I had gone on with it, if only for a few years, what a true record it would have been of a colonial girl’s life with romance enough for more than one novel, what a graphic account of the Maori War, what we did & suffered & went through in those days. But to return to the diary.

It was before the War, when we lived in the forest. I used to write down all I did, where I went, what people I met and what they said to me, sometimes I wrote the stories people told as we sat round the fire. One day my mother got hold of my diary, she went into her room & for hours read it to my father. I heard them laughing very much; one of my sisters [told] me what they were reading. I was in a great rage, and as soon as I could get the book put it into the fire, alas! My mother not knowing what I had done told me how very much pleased she was with what I had written, only she wished to point out how I might do better in future & that I must be very careful how I wrote about other people. She was very much vexed when she found what I had done & also that I would not go on with the diary.

And now after all these years I commence again, just to trace if I can the fate of my latest work, a four-fold screen upon which I have been working for some months. The actual painting was nearly finished about the beginning of July. There was an advertisement in the Mail saying that all exhibits must be shipped for Wellington on the 6th. I went to Fleming to see if he could get the frame ready by that date. He thought he could, he would put it in the frame on Saturday night & put it in the window, on Monday he would finish it off & send it to me. Then I went to Mr Scaife & asked him if I could send my exhibits on Thursday the [9th], instead of Tuesday, as although they would be finished yet I should like to see if they wanted retouching in any way, besides which I was quite sure the Committee would not want to have them so long beforehand. Mr Scaife very politely gave me permission to send them on Thursday.

Saturday [4 July]. I did not like to go & see if it was in the window. Ellen had to go into town so she said there was a small crowd round the window. Frances was in at Mrs White’s. Mr White came back from town, he said ‘I saw your sister’s screen in Fleming’s window, it looks very well. I like it very much.’ Mrs Rodgerson & Lillie had tea with us on Sunday, they had passed Fleming’s window on Saturday & saw a crowd round it.

Monday. We got all the other things arranged in the drawing room, viz. a three-fold screen, white flowers painted on black satin. I made up my mind quite at the last to send that one, I did not like sparing it out of the drawing room, but from its being so different from the other I thought it might be as well to send it, a small table screen, ‘Spring Flowers’, that had been painted some time, a fan, which had been to the Auckland Art Students Ex. last year, a mantel drape ditto, the drape had wreaths of Kowhai flowers worked in silks from my paintings, it won a third prize in Auckland, I improved it a little after it came back, a small table-top made up the list. Somehow I felt dreadfully dissatisfied with all I had done.

About half past three o’clock [Ellen] had to go into town, she met Fleming & asked when the screen would be sent home, to her astonishment found that he had only just taken it out of the window & there was a lot to do to it.

Tuesday afternoon I had a room full of ladies waiting to see this screen. Most of them had seen the other things, some had to go without getting a sight of it. At last Fleming came with it, I had got it into my head that it would turn out a partial failure but as soon as it was opened out in the room I saw that it would do. The ebonised frame & fretwork harmonised well with the cream satin & toned down the painting. The visitors were very much charmed & surprised. Mrs Hardcastle was a splendid show woman, pointing out everything. I was pleased that she took so much interest in it because she has exhibited her pictures in the Royal Academy in London.

Wednesday morning our breakfast was rather late. I was just going to sit down when Mr Scaife came to look at the things. There was no mistake about his being pleased, he said, ‘You need not send them tomorrow, just come & tell me when you wish them to go & I will see them off.’ He had just gone when Mrs Scaife and Miss Elliott came, she was in raptures. ‘But,’ she said, ‘I’m not going to give up my partiality for the black satin screen that was painted & in Fleming’s window. My son came home and said that Miss Harris had painted the most beautiful thing he had ever seen in his life.’

Just after they went Colonel Branfill came, he was in one of his most critical moods with regard to the new screen, he thought some of the painting beautifully done, could not have been better, some bits he would have liked a little altered and some he would like differently arranged. ‘You must not mind what I say, I am not infallible, it is just because it is so good that I say plainly what I think.’ I never do mind what he says, I always pay the greatest attention to his remarks & also to Mr Gully’s so that I may improve. When he was gone I darkened a shadow that he pointed out, but do not think his idea of arrangement as good as my own. All day people kept coming in.

Thursday morning Mrs Suter came, & all day friends came, & a few strangers. Compliments were the order of the day, of course. One curious thing, so many people thought the lycopodium on the black satin screen was real, stuck on in fact, from the very first when it was in Fleming’s window, & two workmen were heard betting about [it]. One said it was real, the other that it was painted so they went in to enquire. It has been the same, not that I find it any advantage people thinking so, for few persons find out their mistake.

Friday & Saturday very few came because the screens were supposed to be sent off. On Sunday Miss Hamilton, Mistress of the Wellington High School, came. She was staying at the Mabins’ for the holidays, she knew Florence Dunnage so Ellen called on her. At Mrs Mabin’s they all liked her so much that Ellen had to ask if she would like to come & see her sister’s paintings for the Wellington Exhibition. So she came thinking perhaps that she was going to see some ordinary flower paintings not knowing what in fact. Her surprise was intense. After looking a minute she sank down upon a seat saying, ‘Yes I see, I was not prepared. No, don’t speak, such works should be looked at with reverence,’ and more she said which I cannot write. When she had gone I felt it was something to have the power to give such great pleasure to anyone. It is a fact strange perhaps yet true, how little I think about & how seldom I remember the compliments I receive, but this lady’s was unusual.

On Monday [13 July] Fleming came and put all the things in the cases with the greatest care, then he left two young men to finish the packing while I looked after them, so if anything happened it would not be the fault of the packing & each case had two large printed Exhibition labels on them. Tuesday morning the cases were gone before I got up. I felt it quite a relief and as school began the next day, it seemed as if I had got [no] holiday instead of three weeks.

And now, I cannot get over the feeling that after all my labour I shall [have] no reward, no prize, no notice, no sale for them, no nothing as the children say. I have no faith in the judges, yet I feel sure that hundreds of people will look upon my work with pleasure, but that won’t fill my empty pockets.

July 23rd [Thursday]. I received a telegram which disgusted me. Viz. Exhibits not received. By what steamer sent & to whom addressed. I rushed off to Mr Scaife with the telegram, he was amazed as well he might be. He had telegraphed when the things were sent from Nelson & nothing that should have been done was omitted. He at once sent a telegram from me to Noel Barraud, and a few hours after came a reply, ‘Exhibits received all right.’

What a set of idiots they must be over there, & where have those cases been all this time. I’m not at all sure about their being all right. After worrying people so to send their exhibits, it shows that they were not nearly ready for them.

Sunday [26 July]. Met Colonel Branfill, he asked if I knew that his exhibits had been lost & had not been found for a fortnight, when at last they were found on the Wellington wharf. I hardly know how to express my indignation after all the trouble we had taken. Mr Gully has sent his pictures at last, he was going over with them but he has a bad leg. He took a cabin passage for them & had them put in a cabin. He thought that if put in a case they would be put in the hold of the steamer & most likely the glass broken. Mr Scaife telegraphed over for three good men to be sent to the wharf to carry them to the Exhibition.

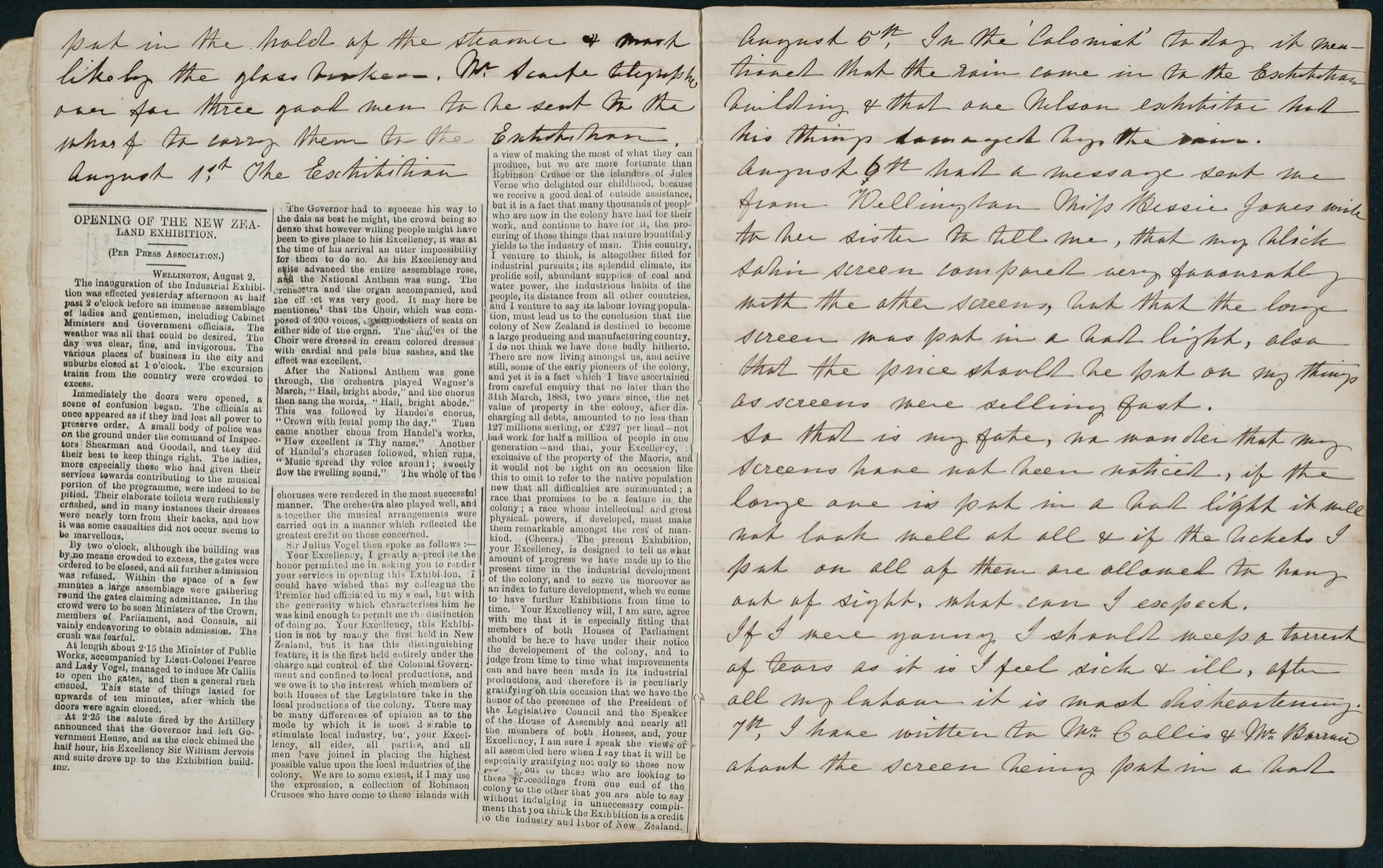

August 1st. The Exhibition.

[Newspaper cutting pasted into diary]

OPENING OF THE NEW ZEALAND EXHIBITION.

(Per Press Association.)

Wellington, August 2.

The inauguration of the Industrial Exhibition was effected yesterday afternoon at half past 2 o’clock before an immense assemblage of ladies and gentlemen, including Cabinet Ministers and Government officials. The weather was all that could be desired. The day was clear, fine, and invigorous. The various places of business in the city and suburbs closed at 1 o’clock. The excursion trains from the country were crowded to excess.

Immediately the doors were opened, a scene of confusion began. The officials at once appeared as if they had lost all power to preserve order. A small body of police was on the ground under the command of Inspectors Shearman and Goodall, and they did their best to keep things right. The ladies, more especially those who had given their services towards contributing to the musical portion of the programme, were indeed to be pitied. Their elaborate toilets were ruthlessly crushed, and in many instances their dresses were nearly torn from their backs, and how it was some casualties did not occur seems to be marvellous.

By two o’clock, although the building was by no means crowded to excess, the gates were ordered to be closed, and all further admission was refused. Within the space of a few minutes a large assemblage were gathering round the gates claiming admittance. In the crowd were to be seen Ministers of the Crown, members of Parliament, and Consuls, all vainly endeavouring to obtain admission. The crush was fearful.

At length about 2.15 the Minister of Public Works, accompanied by Lieut-Colonel Pearce and Lady Vogel, managed to induce Mr Callis to open the gates, and then a general rush ensued. This state of things lasted for upwards of ten minutes, after which the doors were again closed.

At 2.25 the salute fired by the Artillery announced that the Governor had left Government House, and as the clock chimed the half hour, his Excellency Sir William Jervois and suite drove up to the Exhibition building.

The Governor had to squeeze his way to the dais as best he might, the crowd being so dense that however willing people might have been to give place to his Excellency, it was at the time of his arrival an utter impossibility for them to do so. As his Excellency and suite advanced the entire assemblage rose, and the National Anthem was sung. The orchestra and the organ accompanied, and the effect was very good. It may here be mentioned that the Choir, which was composed of 200 voices, occupied tiers of seats on either side of the organ. The ladies of the Choir were dressed in cream colored dresses with cardinal and pale blue sashes, and the effect was excellent.

After the National Anthem was gone through, the orchestra played Wagner’s March, “Hail, bright abode,” and the chorus then sang the words, “Hail, bright abode.” This was followed by Handel’s chorus, “Crown with festal pomp the day.” Then came another chorus from Handel’s works, “How excellent is Thy name.” Another of Handel’s choruses followed, which runs, “Music spread thy voice around; sweetly flow the swelling sound.” The whole of the choruses were rendered in the most successful manner. The orchestra also played well, and altogether the musical arrangements were carried out in a manner which reflected the greatest credit on those concerned.

Sir Julius Vogel then spoke as follows: —

Your Excellency, I greatly appreciate the honor permitted me in asking you to render your services in opening this Exhibition. I could have wished that my colleague the Premier had officiated in my stead, but with the generosity which characterises him he was kind enough to permit me the distinction of doing so. Your Excellency, this Exhibition is not by many the first held in New Zealand, but it has this distinguishing feature, it is the first held entirely under the charge and control of the Colonial Government and confined to local productions, and we owe it to the interest which members of both Houses of the Legislature take in the local productions of the colony. There may be many differences of opinion as to the mode by which it is most desirable to stimulate local industry, but, your Excellency, all sides, all parties, and all men have joined in placing the highest possible value upon the local industries of the colony. We are to some extent, if I may use the expression, a collection of Robinson Crusoes who have come to these islands with a view of making the most of what they can produce, but we are more fortunate than Robinson Crusoe or the islanders of Jules Verne who delighted our childhood, because we receive a good deal of outside assistance, but it is a fact that many thousands of people who are now in the colony have had for their work, and continue to have for it, the procuring of those things that nature bountifully yields to the industry of man.

This country, I venture to think, is altogether fitted for industrial pursuits; its splendid climate, its prolific soil, abundant supplies of coal and water power, the industrious habits of the people, its distance from all other countries, and I venture to say its labour loving population, must lead us to the conclusion that the colony of New Zealand is destined to become a large producing and manufacturing country. I do not think we have done badly hitherto. There are now living amongst us, and active still, some of the early pioneers of the colony, and yet it is a fact which I have ascertained from careful enquiry that no later than the 31th March, 1883, two years since, the net value of property in the colony, after discharging all debts, amounted to no less than 127 millions sterling, or £227 per head — not bad work for half a million of people in one generation — and that, your Excellency, is exclusive of the property of the Maoris, and it would not be right on an occasion like this to omit to refer to the native population now that all difficulties are surmounted; a race that promises to be a feature in the colony; a race whose intellectual and great physical powers, if developed, must make them remarkable amongst the rest of mankind. (Cheers.)

The present Exhibition, your Excellency, is designed to tell us what amount of progress we have made up to the present time in the industrial development of the colony, and to serve us moreover as an index to future development, when we come to have further Exhibitions from time to time. Your Excellency will, I am sure, agree with me that it is especially fitting that members of both Houses of Parliament should be here to have under their notice the development of the colony, and to judge from time to time what improvements can and have been made in its industrial productions, and therefore it is peculiarly gratifying on this occasion that we have the honor of the presence of the President of the Legislative Council and the Speaker of the House of Assembly and nearly all the members of both Houses, and, your Excellency, I am sure I speak the views of all assembled here when I say that it will be especially gratifying not only to those now present but to those who are looking to these proceedings from one end of the colony to the other that you are able to say without indulging in unnecessary compliment that you think the Exhibition is a credit to the industry and labor of New Zealand.

August 5th [Wednesday]. In the Colonist today it mentioned that the rain came in to the Exhibition building & that one Nelson exhibitor had his things damaged by the rain.

August 6th. Had a message sent me from Wellington. Miss Bessie Jones wrote to her sister to tell me that my black satin screen compared very favourably with the other screens, but that the large screen was put in a bad light, also that the price should be put on my things as screens were selling fast.

So that is my fate, no wonder that my screens have not been noticed, if the large one is put in a bad light it will not look well at all & if the tickets I put on all of them are allowed to hang out of sight, what can I expect. If I were young I should weep a torrent of tears, as it is I feel sick & ill, after all my labour it is most disheartening.

[August] 7th. I have written to Mr Callis & Mr Barraud about the screen being put in a bad position, it may not be of any use but it will let them know that I feel myself badly used.

There have been several notices in the papers of the pictures, Mr Gully’s, Mr Richmond’s, Col. Branfill’s & some others very much praised. Ellen & I had today letters from the Rev. J. Taylor D. D.; in mine Dr Taylor says, ‘Many thanks for the verses which I shall prize as a souvenir. I really regret that I did not know you personally better while I was in Nelson. It was only at the very last that I knew you as I now remember with pleasure, & regret too. Had you been trained to write in earlier days you would have done well & been able to earn by your pen an honourable income & position.’

And so he, a clever man, has come to that conclusion. It makes me very sad to think how my life has been wasted. Why could I not have met a Dr Taylor before, to help, direct & encourage me.

[August] 8th [Saturday]. Went with Frances & three other ladies up Brook Street Valley on a ferning expedition. I have not been feeling well & thought a day out of doors would do me good. We got to a lovely spot where thousands of Maidenhair ferns grew on the banks over-hanging the river. Three times we made a bridge of stones to cross & recross the water & were quite enjoying ourselves when suddenly we came upon a poor dead cow with its face half torn away by dogs, and as if that were not sufficient we came just after upon a dead cat very much mangled. Silly as it may seem I cannot get over the sight even yet, it spoiled the day for me & although I was careful not to say much it has made me feel sick ever since.

Notwithstanding that we were dreadfully fatigued. When we came home we carefully planted our ferns in tins and then at nine o’clock just as I was going upstairs to go to bed Colonel Branfill came to ask me about something, he stayed an hour or more. He mentioned that my name was in one of the papers.

Ellen, when she came back from the Mabins’, said they had read a few words in the Colonist, ‘Miss Harris’s screens were pretty and original.’ They were very much disappointed that so little was said. I should not have minded its only being a few words if I liked the words, but, ‘pretty.’ The writer could not have known anything about Art or he would not have used such a word for either of the screens.

[Newspaper cutting pasted into diary, continuation of exhibition opening]

(Cheers.) I will not, your Excellency, refer to another Exhibition which takes place very shortly, I can only say that this present Exhibition represents what may be done by the union of labor and capital, and shortly we shall, in the home industry branch, have an illustration of what may be done by the unaided industry of the individual alone before. In concluding I hope I may be allowed to remark that we are first of all greatly indebted to the unwearying exertions of Doctor Hector, upon whom has devolved a vast amount of work in connection with this Exhibition. (Cheers.) I may here also say that we are indebted to Mr Callis for the extraordinary zeal and aptitude he has displayed, and I must not forget to mention the services of Mr Keyworth, and, your Excellency, it is remarkable in connection with this Exhibition how much we owe to the gratuitous aid of people in all parts of the colony. I cannot too gratefully acknowledge the efforts which have enabled us to produce the Exhibition in a comparatively economical manner and in such a way as will render it possible to hold other Exhibitions of a like kind from time to time. It will now be only for me to say on behalf of those around me, in the presence of the members of both Houses of the Legislature, the high officials of the State, in the presence of representatives from all parts of the colony, including the Mayors of the principal cities, how greatly we feel indebted to your Excellency for your attendance at the opening of the Exhibition, and I am expression their opinions, I am sure, in saying I hope this will not be the last occasion on which you will render a like service in connection with other Exhibitions. (Cheers.) I will ask your Excellency to address this great gathering and declare the Exhibition open. (Loud applause.)

The Governor’s speech we reported on Saturday.

[Newspaper cutting pasted into diary]

ART SECTION.

Colonel Branfill, of Nelson, sends a landscape in oils, and a “Study from Still Life; Nelson Fruit.” To both of these we would direct especial notice, as being works which are well worthy of attention. The latter is quite a little gem in its way. In the landscape subject the artist represents a scene near Nelson in a bold and truthful style. There is, however, a sameness in the colouring, which shows that the artist did not select the most favorable time of day for his sketch. The addition of some stronger colour and a few bright lights in the middle distance would greatly improve the picture. The fore-ground is almost pre-Raphaelite in the careful manner in which minute objects are introduced. A fine colley dog mustering sheep, serves to introduce life and interest into the picture.

Mr J. C. Richmond is an exhibitor in oils as well as in water colours, and shows by his painting of a “Bush Settler’s Home” that he is equally at home in both departments.

Mr Gully contributes seven paintings, occupying the centre of the principal wall. Three of these are of great size, the most striking one being “A View in Blind Bay.” This is a magnificent picture, and one well calculated to sustain the artist’s high reputation. It represent a panoramic view from the hill on the western side of Blind Bay looking northwards. The painting is rich in colour, and the atmospheric effect in the distance is beautifully conveyed. A group of fine cattle is introduced into the foreground with good effect. Altogether the picture is one of which the citizens of Nelson, for whom, we believe, it was painted, may well be proud. Mr Gully’s other two large pictures are views at the Kaikouras, both fine paintings, but we should hardly imagine the subjects to have been selected by the artist himself for such large works. The picture which we consider the gem from Mr Gully’s studio on this occasion is a smaller view of Kaikoura, in which an effect of sunlight breaking through a clouded sky is happily conveyed. “A Scene on the West Coast Road,” with a drove of cattle in the foreground, is also a striking picture.

Mr J. C. Richmond, whose paintings are well known throughout New Zealand, exhibits several outdoor landscape studies full of freshness and life, also a finished painting of Milford Sound. Mr Richmond shows in this work that he possesses not only a thorough knowledge of technique, but also that he has the trained artist’s eye. The rich coloring of the mountains reflected in the glassy waters of the Sound, the snow-clad mass of Mount Pembroke, and the densely wooded “Lion” are portrayed with faithfulness to nature, and form a charming picture, and one which will find many genuine admirers.

[Newspaper cutting pasted into diary]

MR GULLY’S PICTURES.

(N.Z. Times)

The most important pictures in the Exhibition are those of Mr John Gully, of Nelson. He has seven water-coloring drawings of various sizes. No. 1 is a large picture of the West Coast of Tasman Bay, showing a long sweep of sea beach to the left, with breaking surf and hills in the distance. The sky is cloudy, with only patches of blue. The picture is a very fine one, showing many of the characteristic merits of the painter — purity and harmony of color, atmosphere and skill in depicting the herbage in the foreground. The chief fault to be found is that there is some wooliness and want of crispness about the painting of the breakers. No. 2 is a view of the Kaikoura Mountains, with a foreground of foliage and herbage and a smooth sea to the right. It is an exceedingly attractive picture, the distance and transparency of the water being particularly fine. No. 3 (South Coast of Kaikoura) is another coast scene, with a great mass of wood in the foreground. Here Mr Gully is in his element, and shows his rare skill in representing New Zealand foliage. The smooth water, distant hills, and sky are also here painted with great purity.

The gem of the lot, however, is the small picture, No. 5, “The Port of Kaikoura.” For its color, composition, and handling it deserves high praise, and the effect of light and shade is beautiful. No. 6 is the only picture of Mr Gully’s of an inland scene; it is a view of the West Coast Road looking down the Bealey, and is perhaps the second best. The drawing, color, distance, and effect are thoroughly good, and the light is skilfully and tellingly brought into the foreground. Nos. 4 and 7 are of an entirely different style from the others, and might, from appearances, be the work of another painter. They are somewhat after the manner of Aaron Penley, and, though possessing harmony of color and several other good qualities in which Mr Gully is never lacking they do not give the same pleasure as those in which he follows his natural bent. Altogether the pictures contributed by this artist are a credit to the Colony, which may be congratulated on possessing a painter who has with the highest success made it his study to depict the peculiar beauties of New Zealand.

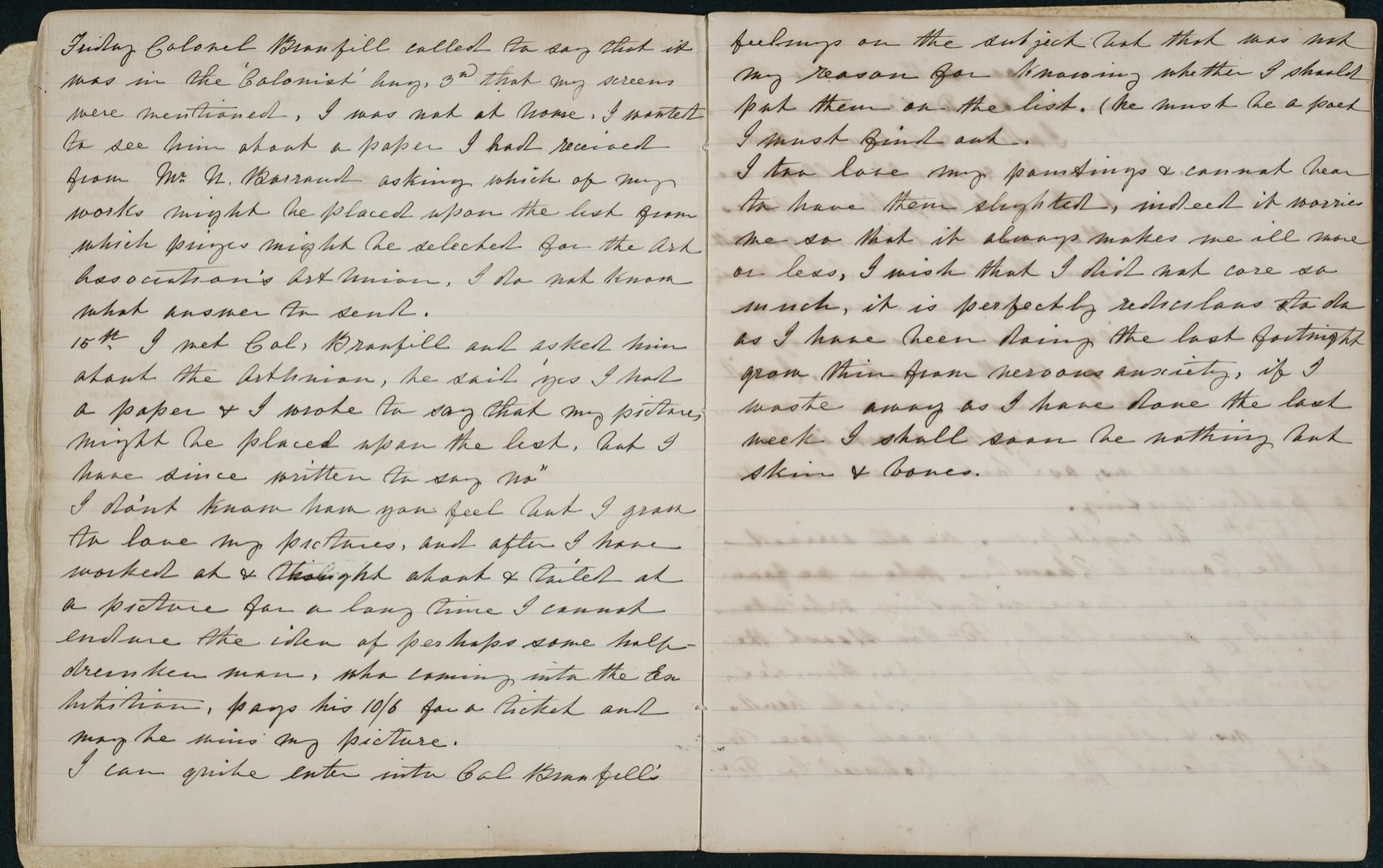

Friday [14 August]. Colonel Branfill called to say that it was in the Colonist Aug 3rd that my screens were mentioned. I was not at home. I wanted to see him about a paper I had received from Mr N. Barraud asking which of my works might be placed upon the list from which prizes might be selected for the Art Association’s Art Union. I do not know what answer to send.

15th [August]. I met Col. Branfill and asked him about the Art Union, he said, ‘Yes I had a paper & I wrote to say that my pictures might be placed upon the list, but I have since written to say no. I don’t know how you feel but I grow to love my pictures, and after I have worked at & thought about & toiled at a picture for a long time I cannot endure the idea of perhaps some half drunken man, who coming into the Exhibition, pays his 10/6 and maybe wins my picture.’

I can quite enter into Col. Branfill’s feelings on the subject, but that was not my reason for [not] knowing whether I should put them on the list. (He must be a poet. I must find out).

I too love my paintings & cannot bear to have them slighted, indeed it worries me so that it always makes me ill more or less. I wish that I did not care so much, it is perfectly ridiculous to do as I have been doing the last fortnight, grown thin from nervous anxiety. If I waste away as I have done the last week, I shall soon be nothing but skin & bones.

Notes

August 2nd 1885 [Sunday]

Emily Harris begins her diary on the day after the New Zealand Industrial Exhibition opening in Wellington. She has not kept a diary since her girlhood in Taranaki before the war of 1860-61 and now wants to record responses to her submissions to this and other exhibitions. Sunday becomes a favourite day for updating the diary and her first entry reviews the events of July leading up to the dispatch of works to Wellington.

Colonel Branfill told us the other evening

Lieutenant-Colonel Benjamin Aylett Branfill (1828-1899) emigrated to Nelson in 1881 after retiring from the British Army in 1877. He left his wife and children in England to take up a life focused on art, religious study, music, horticulture and photography. A daughter, Helen (Nell) Hammond Branfill joined him in Nelson in 1886 and married the Reverend Howard Percival Cowx in 1891. Branfill’s extensive papers, including his diaries, were acquired by the University of Toronto in 2016. A finding aid is available.

When the Bishopdale Sketching Club was established in 1889, Branfill was a founding member and became the club’s monthly critic in 1891. In 1892 he lectured twice to club members on ‘artistic anatomy’ in Emily Harris’s studio. (Neale 2-4)

We told him that our mother had kept a book

Sarah Harris (1806-1879) compiled her notes on family history in 1871, recalling her childhood in Plymouth, England, her marriage to Edwin Harris in 1833 and their emigration to New Plymouth in 1840-41. Sarah copied letters about her New Zealand experiences into the notebook and added material to 1874. After her death, her daughters and their children added material through to 1941. The notebook is an important source text for ‘The Family Songbook’ (2019) and belongs to Sarah’s great-great-grandson Godfrey JW Briant, Marton.

It was before the War, when we lived in the forest

Emily refers to the years (1848-1860) when the Harrises lived on a 50-acre rural section on Frankley Road in New Plymouth. Edwin Harris surveyed the Grey Block for Donald McLean in 1847 and purchased the section with funds sent from England by his brother-in-law James Meadows Rendel. Sarah Harris and her daughters Emily and Catherine (Kate) taught in two schools kept by Sarah in the Frankley Road (Hurdon) area in the 1850s. When war broke out in March 1860, the Harris family left their farm to come into town and did not return, relocating to Nelson in 1861 and eventually selling the property to artist Francis Hamar Arden in 1876. See ‘The Family Songbook’ 21-31.

I went to Fleming to see if he could get the frame ready by that date

George Fleming and Sons, Hardy St, Nelson, were furnishers whose business included picture framing as well as the manufacture and renovation of furniture.

Then I went to Mr Scaife

Arthur Ashton Scaife (1855-1923) was born in Greenwich, Kent, and emigrated with his family to Nelson in 1856. He married Maud Catley in Nelson in 1889 and later moved to Australia where he died in Heidelberg, Melbourne. In 1885, Scaife was secretary of the Nelson Chamber of Commerce which was acting as a local subcommittee for the Industrial Exhibition. (Death Reg. 1901/1923 Victoria BDM Search)

Ellen had to go into town

Ellen Harris (1851-1895) was the youngest child of Edwin and Sarah Harris. She became an artist and teacher like her sisters Emily and Frances but her work has not been recovered. She was a member of the Bishopdale Sketching Club and a contributor to the club’s first catalogue in 1893. Ellen died 29 Mar 1895 in Nelson and was buried in Wakapuaka Cemetery. Her death certificate notes cause of death as chronic phthisis (Tuberculosis) of the lungs. See ‘Sisters at a Glance: #7 Ellen Harris’ (22 Oct 2020).

Frances was in at Mrs White’s

Frances Emma Harris (1842-1892) was the fifth child of Edwin and Sarah Harris, and the first born in New Zealand. She was probably given art training by her father and examples of her work are held by Puke Ariki Museum in New Plymouth and by Harris descendant Peter Tregeagle, Sydney. Her illustrated journal ‘Ascent of Mount Egmont, March 11th 1879’ belongs to Godfrey JW and Judith Briant. Frances died in New Plymouth while staying with married sister Mary Weyergang and was buried at St Mary’s Church with her brother Corbyn. Her death certificate notes cause of death as Influenza 3 months, Phthisis 6 months. See ‘Sisters at a Glance: #4 Frances Emma Harris’ (27 Aug 2020).

Emma White (1848-1928) was the wife of Stephen Brown White (1839-1921). The Whites lived in nearby Shelbourne St. Their interest in Emily’s work goes back at least as far as the 1882 notice about some of the items she intended sending to the Christchurch International Exhibition of that year:

The paintings are on black satin, and are intended for a table cover, two hand screens, a bracket, and a mantelpiece border, and although the flowers are different the same idea has been carried out in each, the centre being a beautiful cluster, consisting principally of geraniums, pansies, lilies, and other well known flowers, while the border is of white clematis, and pendent at the corners of the table cover and the centre of the brackets are magnificent white and red fuchsias that on the mantelpiece bracket being of so enormous a size as almost to give the impression that it is exaggerated, but Miss Harris assures us that it is an exact copy of a splendid blossom grown by Mr S. B. White in his greenhouse. (Nelson Evening Mail 16 Mar 1882: 2)

On Emma White’s death an oil painting by Emily Harris entitled ‘Kowhai and Bellbirds’ was gifted by the terms of the will of SB White to the Suter Art Gallery as part of a larger bequest:

The Suter Art Gallery has recently been enriched by the accession of a number of valuable pictures, and ten of these are being exhibited this week for the first time. […] A considerable number of pictures of varying merit were bequeathed to the Gallery by the late Mr and Mrs S. B. White. Some of them are of considerable value and foremost among them are some landscapes by John Gully, including an exceptionally fine one of Mount Egmont. Mr S. B. White used to relate that Gully, after selling this picture to him, used to call at his house from time to time to examine it again, as the artist always considered it as one of his best pieces of work. (Nelson Evening Mail 26 Dec 1928: 4)

The oil painting by Emily Harris, 190 x 285mm, could not be located in 1964 or 1980 catalogues and was de-accessioned after 2010. (Suter Records. Accession No: 160.2)

Mrs Rodgerson & Lillie had tea with us on Sunday

Clara Hortensia Rodgerson, née Kingdon (1826-1905) and her daughter Clara Louisa (Lillie) Burton (1862-1940). Both women are good friends of the Harris family, a connection that probably goes back to Taranaki days when Clara was married to George Rutt Burton who was a captain in the Taranaki Militia during the war of 1860. After Burton’s death Clara married William James Rodgerson of Nelson. (Colonist 26 Dec 1865: 2). In 1885, she is again a widow and lives in Brougham St, Nelson. In 1889, she advertised for a general servant and in 1895 her six-roomed house on a half-acre section (‘well planted with fruit trees’) was advertised to let. (Nelson Evening Mail 8 Apr 1889: 2; 4 Mar 1895: 3) Clara Rodgerson and Clara Louisa Burton are buried together in Wakapuaka Cemetery, Nelson.

Monday. We got all the other things arranged in the drawing room

Emily’s six submissions comprise decorative work, at the time popular with the art-buying public and almost always produced by women artists. It is fortunate that Emily describes the works in her diary, since like many other entries in the Special Art Section of the exhibition catalogue they are not itemised nor are their prices given: ‘736—Harris, Emily C., Nelson. Oil and Water-Colour Painting on Satin; all original.’

Mrs Hardcastle was a splendid show woman

Charlotte Hardcastle (1828-1908) was an English painter who exhibited flower and bird studies at the Royal Society of British Artists, the British Institution and the Royal Academy in the 1850s and 1860s. In 1868 she travelled to Australia and married her cousin Edward Hardcastle in Melbourne, returning with him to Hokitika on the West Coast of the South Island of New Zealand where he had been appointed as a law clerk earlier that year. The Hardcastles had two children in Hokitika, Edward Patrick Edgington Murrough (1869-1948) and Kathleen Charlotte Maud (or Maria) (1872-1932). The Hardcastles were in Whanganui by 1877 and Edward was appointed resident magistrate there. He became a district judge and the family was living in Wellington when Edward fell ill in 1884 and the Hardcastles moved to Nelson. They were living in Nile St East when Edward died in January 1886, aged 49. Charlotte, Edward Edgington and Kathleen relocated to Christchurch and Wellington, and by 1902 Charlotte and Kathleen were resident again in Whanganui. The Sarjeant Gallery holds six botanical watercolour studies by Charlotte Hardcastle.

Also see blog post ‘Mrs Hardcastle was a splendid show woman’ (26 Mar 2020) and ‘Sarjeant Gallery: Reseachers add to story of Whanganui artist Charlotte Hardcastle’ (28 April 2020) from the Whanganui Chronicle.

He had just gone when Mrs Scaife and Miss Elliott came

Eliza Scaife, née Ashton (1832-1889), was the mother of Arthur Ashton Scaife. She prefers the black satin screen that was also displayed in Fleming’s window at an earlier date. Her companion Miss Elliott has not been identified.

I always pay the greatest attention to his remarks & also to Mr Gully’s

John Gully (1819-1888) was a largely self-taught artist who became the pre-eminent landscape painter of Nelson from the 1860s. He was born in Bath, Somerset, and emigrated to New Plymouth with his wife Jane, stepson Ambrose Moore and three younger children in 1852. The Harrises and the Gullys knew each other in Taranaki and continued their friendship when both families relocated to Nelson after the Taranaki war of 1860-61. Gully became drawing master at Nelson College in 1861, then a draughtsman at the Department of Lands and Survey 1863-1878. His reputation as a watercolourist and painter in oils grew steadily through the 1870s and 1880s (Te Papa). John and Jane Gully lived in Trafalgar St, Nelson, close to the Harris family at 34 Nile St.

Thursday morning Mrs Suter came

Amelia Damaris Suter, née Harrison (1828-1896). She married Andrew Burn Suter, an Anglican vicar, in 1860 and after he was consecrated Bishop of Nelson in 1866 the couple left England for New Zealand in 1867. They established Bishopdale as a residential theological college in 1869 and lived on the estate with students training for the ministry. Amelia Suter returned to England after the death of her husband in 1895 and died in Barham the following year. She bequeathed a collection of paintings to form the nucleus of the collection of the Bishop Suter Art Gallery, which opened in Nelson in 1899. (DNZB)

On Sunday Miss Hamilton, Mistress of the Wellington High School, came

Like Nelson College for Girls, established in 1883 long after Nelson College (for boys), Wellington Girls’ College was founded years after its brother institution and had to fight for space and resources:

After some dabbling with the idea of higher education for girls at Wellington College in the 1870s, the founding fathers of this school (and they were all men) decided to lease a building in Abel Smith St, and in October 1882 a ‘Lady Principal’ was appointed to open Wellington Girls’ High School. Miss Martha Hamilton came from Christchurch and the school opened on 2 February 1883, with 40 girls.

Girls were expected to learn from a very broad range of subjects – many very similar to those we study today: French, Algebra, Sciences, History, Maths, English, Geography and Drawing we recognise. Calisthenics might not be so clearly understood. Girls intending to go to university studied Latin. It was a private school so parents paid full fees and they had some say in what was taught – which was how Drawing, Needlework and Vocal Music all came to be in the curriculum.

By the end of 1883 there were nearly 100 students and the school was overflowing. Miss Hamilton was clearly a woman with a strategic approach. In 1884 the Premier, the Rt. Hon. Robert Stout visited the school. He saw extremely crowded classrooms, with girls sitting three to a seat and when the bell rang part way through his visit, all 130 girls, 5 staff and 4 visitors spilled into the tiny corridors as everyone changed rooms. Sir Robert declared that he didn’t know things were so bad; Miss Hamilton replied, ‘We cope as best we can. I have written to the Government asking for a tent.’ As a result of this visit, the Pipitea St site was made available and the school we are now part of began to take shape. Miss Hamilton left in 1900. (History, Wellington Girls’ College)

She was staying at the Mabins’ for the holidays, she knew Florence Dunnage

The Mabin family lived at 98 Nile St, Nelson (NHS Journal). Florence Dunnage (1858-1942) was a Christchurch teacher who married Henry Ffitch at Papanui in 1884. (Christchurch Star 21 Feb 1877: 3; Press 29 Oct 1884: 2)

Tuesday morning the cases were gone before I got up

Emily, Frances and Ellen Harris all taught in the small private school that had been running since the early 1870s close to (and sometimes in) the family home at 34 Nile St. See ‘The Misses’ Harris school in Nile St’ (5 Mar 2020). An advertisement in the local paper confirms the start of the new term: ‘THE MISSES HARRIS’S SCHOOL, Nile-st. East.—The Third Quarter of current year will begin on WEDNESDAY July 15th.’ (Nelson Evening Mail 15 July 1885: 3)

He at once sent a telegram from me to Noel Barraud

Edward Noel Barraud (1857-1920) was the son of artist Charles Barraud and was an artist himself. He was a founder and first secretary of the Fine Arts Association and was on the first Council of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, Wellington. (Platts) In 1885 Noel Barraud was part of the sub-committee in charge of the exhibits in the Art Gallery at the Industrial Exhibition in Wellington. Three of his paintings appear in the exhibition catalogue.

August 1st. The Exhibition

Nelson Evening Mail 3 Aug 1885: 3. The chaos of the opening ceremony mirrors the disorganisation experienced by exhibitors and exhibition officials as Treasurer Sir Julius Vogel attempted to mount a national exposition without sufficient Government funding. The press was critical of the administrative shortcomings of the exhibition: see ‘Wellington’s Industrial Exhibition a flop in 1885 – 150 years of news.’

Emily cut out the Press Association account of the exhibition opening and pasted it in two parts into her diary. The date of the cutting (August 2) indicates that her review of events leading up to the exhibition is complete. The diary now moves into August as she awaits news of her entries in the Art Section competition.

Miss Bessie Jones wrote to her sister

Bessie Jones was also a contributor to the exhibition: ‘Christmas and birthday cards—Bessie Jones, Nelson, hon. mention.’ (NZ Times 6 Nov 1885: 6). Charles and Eliza Jones, who both died in 1912 and are buried in Richmond Cemetery, Nelson, had four daughters and three sons. Two daughters, Amelia Mary Emily and Nina Lucy Mary, are buried with their parents. If their sister is Bessie Jones she predeceased her parents and has not been further identified. (Colonist 13 Aug 1912: 4)

I have written to Mr Callis

Charles Callis (1843-1914) was an accountant and commission agent. He was born in Meads, Ashby, Northamptonshire, and emigrated to Australia in 1871. In 1879 he settled in Wellington. Callis was secretary of the executive committee charged with the running of the New Zealand Industrial Exhibition of 1885. He had been secretary for the New Zealand Government at the Sydney International Exhibition 1879-1880, and at the Melbourne International Exhibition 1880-1881. (Cyclopedia of NZ) Emily had some personal acquaintance with Charles Callis, perhaps in connection with her visit to Melbourne to see the International Exhibition in 1880. Two cartes de visite at Dunedin Public Libraries, one from a Melbourne studio and one from Wellington, are inscribed: ‘Emily Cumming Harris, 1881’ and ‘For Mrs Callis, with kind love, 8/3/81.’ (ZARCH 280) Mary Jane Thomas (1846-1931) married Charles Callis in Islington, England in 1865. In 1871 they moved to Australia with their three year old son Charles and later moved to New Zealand in 1879. In 1885 Mary Callis became a driving force in the home industry exhibit in the New Zealand Industrial Exhibition in Wellington, where she went to the aid of the exhibit, taking on the desperately needed arranging with some recruited friends (NZ Mail 28 Aug 1885: 4).

There have been several notices in the papers of the pictures, Mr Gully’s, Mr Richmond’s, Col. Branfill’s

Emily cut out two of these and pasted them into her diary. See below, ‘Art Section,’ ‘Mr Gully’s Paintings’ and notes. James Crowe Richmond (1822-1898) was born in London and emigrated to New Plymouth with his younger brother Henry Robert Richmond in 1851, ahead of a family migration of Richmonds and Atkinsons in 1853. He returned to England, married Mary Smith in London in 1856 and arrived in New Zealand with her later that year. Richmond was an engineer, artist, journalist, politician and administrator. He became a friend and patron of John Gully when both families resettled in Nelson after the Taranaki war of 1860-61. Richmond brought up his five children after his wife’s death in 1865 and did not re-marry. (DNZB) He took his children to England and Europe for their education in the 1870s, returning with his sister Jane Maria Atkinson and her daughters via Melbourne in 1880. At New Year 1881, Richmond’s party of nine was on the same excursion sailing from Melbourne as John Gully, Emily Harris and her neighbour Mrs Henrietta Levien. The Te Anau sailed for Fiordland, giving passengers the chance to go ashore briefly at Milford Sound and George Sound before continuing on to Bluff, Port Chalmers, Lyttelton, Wellington, Nelson and Auckland. See ‘Houhere (lacebark) in Flower at Milford Sound’ (18 Apr 2019).

JC Richmond’s daughter, Dorothy Kate Richmond (1861-1935), was in the family party on the Te Anau. She continued to develop the training she had received at the Slade School of Fine Art in London in her father’s Nelson studio until her departure for England in 1885. She returned to Nelson and became a member of the Bishopdale Sketching Club, appearing in its first catalogue in 1893 before leaving Nelson for Wellington with her father in 1894. (DNZB)

Ellen & I had today letters from the Rev. J. Taylor D. D.

Reverend Doctor James Taylor (1810-1898) was born in Dublin, Ireland. He was a graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, and headmaster of Wakefield Grammar School in Yorkshire from 1847 until 1875. He became a Bachelor of Divinity (BD) in 1866 and a Doctor of Divinity (DD) in 1871. In 1884 Taylor and his wife Elizabeth interrupted a world tour to stay for over a year in New Zealand, assisting local clergy in Nelson and Auckland. They continued their tour in July 1885, travelling via Tonga and Tahiti to North America and on to England. (Blain)

The Taylors were based in Nelson from April 1884 until May 1885, Taylor acting as incumbent of Christ Church until the arrival of Reverend John Pratt Kempthorne. During their stay, Taylor gave public lectures and published poems in local newspapers. Of note is an entertaining lecture on ‘Nelson in the year 2000, A.D.’ in which Taylor imagines himself returning to the city on a vessel powered by electricity and suggests growing olive, orange and lemon trees and grape vines in the Nelson region. (Nelson Evening Mail 20 Aug 1884: 2)

In a lecture on his travels in Ireland, Madeira, Switzerland and Greece, Taylor finished by reciting Byron’s ‘The Isles of Greece’: ‘On arriving at the last line, “Dash down yon cup of Samian wine,” he suited the action, in so far as he was able to do so, to the words, and dashed the glass he had in his hand (less the Samian wine) to the floor and with such force as to splinter it into fragments.’ (Nelson Evening Mail 8 Oct 1884: 2)

Taylor also read a lengthy poem, ‘Lines Written on the Occasion of Exhibition of Mr John Gully’s Paintings,’ at the close of an exhibition featuring Gully’s work. (Nelson Evening Mail 1 Oct 1884: 2) The poem ends:

Say who our artist school’d? Who taught his hand,

Untrain’d, to sweep the curve of beauty? who,

To choose the colours, various or adverse,

And blend them all in one harmonious whole?

’Twas Nature’s self. In her wide school he learnt

Lines geometric and the easel’s use.

Here gaudy Iris all her colours blent

For her apt scholar. Meditation taught

Wise combination of the simpler rules,

The grouping of “Rough Sketches” into one.

Sketches of mountains, lakes; of sea and shore;

The Morning’s glow and sombre Evening’s close.

With the long ridges purpling into night,

The landscape, panting in the noontide sun,

Or drowsy ’neath the evening star—all prove

GULLY is Nature’s pupil and her best.

ART SECTION

Colonist 6 Aug 1885: 3. Branfill, James Crowe Richmond and John Gully receive detailed critique of their work as Emily waits in vain for more than passing comments on her entries. Richmond’s landscapes are not itemised in the exhibition catalogue but titles and prices are given for Branfill and titles for Gully.

MR GULLY’S PICTURES

Nelson Evening Mail 15 Aug 1885: 2. Reprinted from the New Zealand Times.

Friday [14 August]. Colonel Branfill called to say that it was in the Colonist Aug 3rd Colonist 7 Aug 1885: 3. Among works by eleven Nelson exhibitors described almost entirely from the alphabetically-arranged catalogue is the comment Emily objects to: ‘Emily C. Harris exhibits oil and water color paintings on satin, all original and very pretty.’

15th [August]. I met Col. Branfill and asked him about the Art Union

Colonial New Zealanders sometimes subscribed to British ‘art unions’ where they invested a guinea or more to be in the draw to win a work of art. New Zealand artists began their own art unions from the 1860s. It allowed art lovers a chance to procure a work of art that they could not otherwise afford. (Te Ara)

Full Navigation

Section 1: August 1885: You Are Here

Section 2: September-November 1885

Section 3: January-March 1886

Section 4: March-July 1886

Section 5: August-November 1886

Section 6: August-December 1888

Section 7: January 1889

Section 8: February-August 1889

Section 9: September-October 1889

Section 10: November-December 1889

Section 11: January-February 1890

Section 12: August 1890-February 1891