In January this year, my partner Cole and I walked the Pouakai circuit, so that I could film flora for I do not like to burn, a short video about the botanical works of Emily Harris. Though the hike is designed to take three days, we decided to do it in two. The Pouakai circuit begins and ends at the Taranaki National Park Visitor Centre, in the northern part of the park; the track winds through the saddle between Mt Taranaki and the Pouakai range, climbing Henry Peak (1220m) in the process. The botany and geography of the area is unique, ranging from native ferns, deciduous cedar groves, ancient swamps and an alpine tarn. On the drive down, I received a serendipitous email from Michele, directing me to the journal of Frances Harris – Emily’s sister. In 1879, Frances walked the Pouakai circuit before summiting Mt Taranaki. Frances was with me as I walked, gazing back through the archive. Thus, two separate projects came to be intertwined. The following is my account of the walk, interspersed with text from Frances’ journal.

Words by Toyah Webb

Photographs by Cole Cochran

Imagine yourself standing on one of the rounded tops of the ranges: at your feet the swamp forms into a half circle round the base of the mountain and numerous spurs of the ranges jut out like green promontories in a yellow sea, whilst a brook that looks no wider than a ditch winds through it. At the back rises the mountain from which the clouds are rolling and we see it in all its grandiose. There is not much snow, but what there is gleams in the sun like jewels set in grey rock. – Frances Harris

Day 1 (05/01/21)

Indentations left by footprints. Leaves and berries crushed by human weight. My shoelaces are tied in knots to hold them together, backpack already slipping off my shoulders. Cole swipes at low-hanging ferns, which slap me as I pass. After thirty minutes of navigating roots and clefts, we come to a sign for the Pouakai hut: 6 hours. I think about other hikes, pitying those committed to the longer route, relieved it isn’t me – but this time, it is. I wave my camera at every flower we pass. After an hour of walking, there is a break in the tree line: our first view of the mountain. Small clouds scud just below patches of remaining snow. We hear river-sounds and the track descends to meet one. Water crashes and tumbles over itself, white and glacier blue. Rings of ourisia shoot out from between the moss-covered rocks. Before us, in mid-air, hangs a bridge – if you could call it that. I’m terrified of heights, especially when the height in question is a strip of chain-mail. I grit my teeth and haul myself across, breath coming in short ragged gasps.

I look up in time to see Cole’s drink bottle slip from the side of his pack and hurtle through space, down to the river below. We are about one hour into a six-hour hike, with one water bottle between us. The river is too high to fill-up from and I am immediately thirsty. Anxiety arrives and settles. On the other side of the crossing, the ascent begins. We clamber over roots, pulling ourselves up the ridge with low branches. The ferns have given way to kamahi, pukatea and rimu trees. After a while we come to a clearing, swarming with native bees. I stop to catch my breath – in the footage filmed here I can be heard making a comment about Frances walking in a wool dress, my disbelief. Soon, another river crossing and Cole fills our remaining water bottle. A view of the mountain. Delicate orchids wave in the breeze.

The track is cut through dense forest and winds about; you cannot see very far ahead. It is impossible to judge of distance or height, for all around these is nothing but trees which meet overhead

The track keeps going up. Endless steep stairs, made for people with longer legs than mine. I feel panic setting in. There is no water, only half a cucumber. At the beginning of every set of stairs Cole says, “we’re nearly at the top”, and then I see his face. Beyond the tree-line, the sun is relentless. On one side is the mountain, on another, the swamp. A river runs through it like a line of silver ore. I think of Frances’ journal – the casual tone with which she describes everything, any emotion almost elided from the page. Written in retrospect surely, like this, but I vividly remember the weight on my chest, straddled between leaving and arriving, stuck halfway up Henry Peak. An exhaustion induced panic attack. Turning on the spot, New Plymouth is visible – a patch of houses, then the ocean. I feel cheated. To seem so remote, yet with the city still visible... I film a short clip of Mt Taranaki but the camera shakes as my hand does.

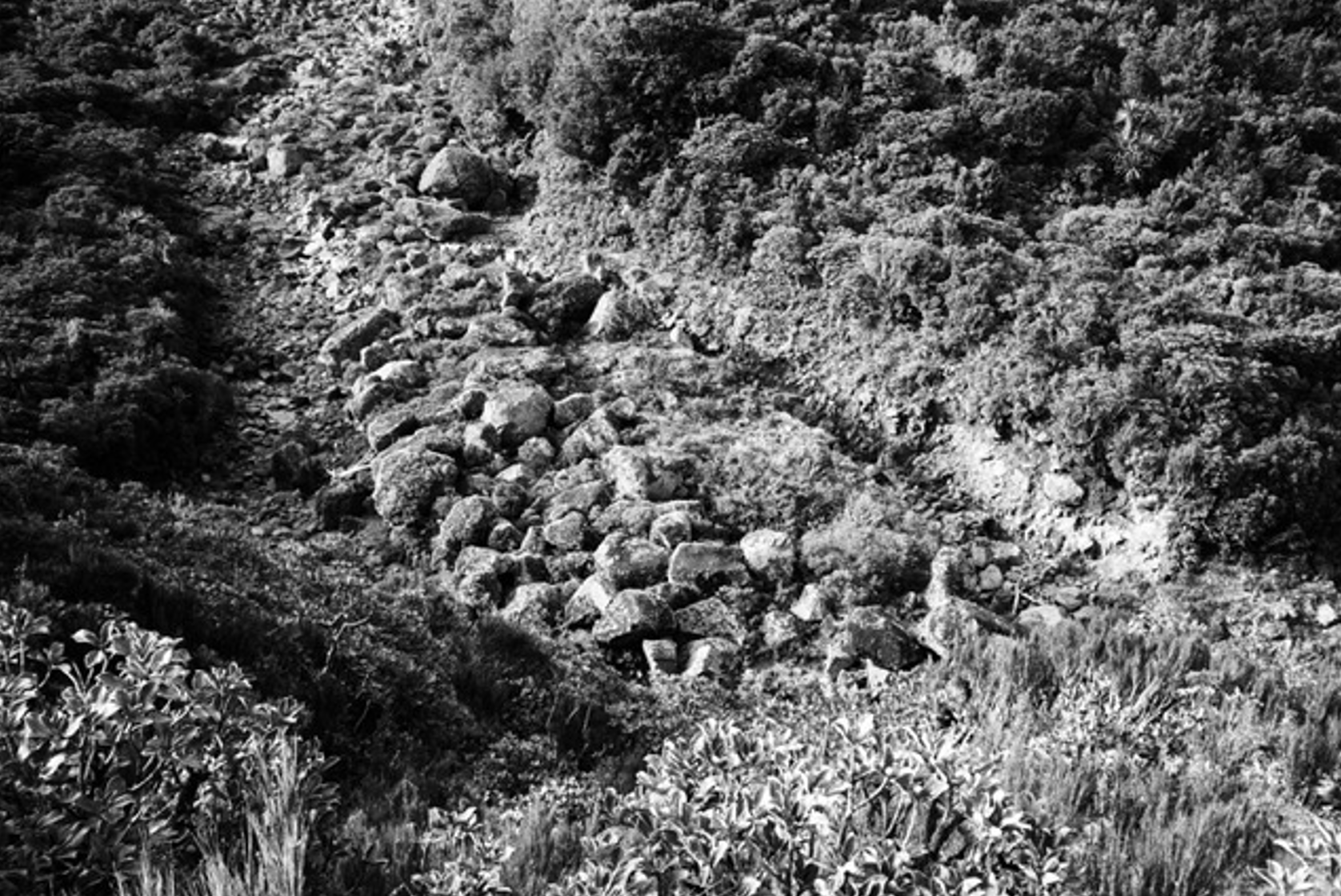

Finally, we reach the top. The landscape is an uneven surface of rocks and grasses, with small alpine flowers scattered like stars. The wind rubs all conversation blank. From the viewing platform resting on Henry’s back (not there in Frances’ day), we can make out the path weaving along the ridgeline. It dips, then rises again and, in the distance, something catches the light. We begin the descent: I am exhausted and dehydrated but relieved that the endless climb is over. There are more flowers on this side of the peak, sheltered by the wind –whole floral worlds under over-hanging rocks. Ourisia is here too, but much smaller than the ringlets we saw earlier.

The ‘Flora’ of the mountain is very beautiful. Cedar trees cover the ranges with their dark green foliage [which] is mingled with the bright red and purple of the Pepper plant, whilst in the more open parts tiny florets gladden the eye at every turn. Amongst the most common are the Primula and several varieties of daisy. […] We found three varieties of bush in flower, lilac, pink & white; very fine Koromiko pure white, and many other flowers whose names I am unacquainted with.

The path is made of individual wooden planks, arranged to form a boardwalk. I try to imagine the people constructing it, clinging to the side of the mountain, stooped in the sun. The boardwalk pauses at the edge of a promontory and is replaced by a ladder to descend. I grit my teeth (again) and grip the metal rails so hard my knuckles turn white. There is another ladder and another, then the track levels out, manuka scrub & hebe on either side. The sun is almost unbearable now. We crouch under a stunted tree half my height to get some shade. The track begins to climb again and suddenly we come to a clearing of tussocky grasses. The path is lined by hundreds of yellow bulbanella, shin height. Strange and alien flowers, they sway in the wind. The boardwalk squelches underfoot: we have arrived in the alpine wetlands.

The bulbanella add drama to the landscape, an upheaval of colour that breaks the ‘sameness’ of the tussock. Cole is overwhelmed by the tall flowers, heads bobbing on skinny necks. I wait while he takes photos. A slight rise and we come to the tarn. Although much smaller than the DOC brochures imply, it is bewitching. A double of the mountain is so perfectly reflected on its glassy surface that it is hard to see the water. We keep walking; what I thought was the roof of the hut flashing in the sun turns out to be a marker for helicopters. I am close to giving up when I hear voices, and the track plateaus. To our left is Mt Taranaki, rising red and brown against the blue sky. Snow is just visible behind its clouded crown. The hut is on another plateau, slightly lower than the first. I take off my pack and lie on a patch of springy green moss, forcing every bone in my back to straighten. Cole finds a tap behind the hut – we need to boil the water before it is safe to drink. I wonder if Frances drank straight from the streams, or whether they carried all their water with them; was it even something people thought about, when the word ‘Nature’ was equivalent to the word ‘pristine’? I am so exhausted that I feel delirious.

I shall never forget the scene as we sat round the fire on tufts of grass. On either side were the tents, before us “Egmont” looking hugely grand but cold and grey. Over a spur the moon was rising, making the shadows more intense. The Southern Cross looked bright and friendly. On our right were thick wooded hills, in the distance we heard the roar of Bell’s Falls broken by the hooting of an owl.

My head pounds, even after endless cups of tea. Frances had a headache after walking too, a common symptom of dehydration and concentration. But I have painkillers, I doubt she did. New Plymouth is visible from the balcony of the hut and again I feel somewhat cheated. A six-hour hike, walking in circles. The sun begins to set, but I am not awake to see it. We set our alarms for 5.15am, so that we can start walking before the sun rises.

Day 2 (06/01/21)

The day begins cool and silent, a light wind rolling up and down the Pouakai range. Taranaki looms dark in the distance, as the first suggestion of sun bleeds the sky orange. The boardwalk continues along the grassy ridge, before dipping down into stunted Manuka trees. Without the heat of mid-afternoon sun, I am full of energy – my pack feels lighter and my feet no longer ache. The track is also relatively flat, and soon the wooden planks are replaced by dirt. I feel grounded. We follow the curve of the range (bypassing the Pouakai summit) and come to another descent: hundreds of stairs laddered down towards the swamp. The swamp is beautiful in the half-light; nestled between the mountains it seems strangely out of place. The river is a thread of gold.

Bleached trees twist into fantastic shapes and each step disturbs a plethora of insect-life. The stairs are steep, the night’s rain pooled in each ledge. Going down, it turns out, is almost as difficult as going up. The sun is in our eyes now, level with the staircase. A sign informs us that the Holly hut is only an hour and a half away. We are on the other side of the Pouakai range and the swamp stretches out between us and Mt Taranaki. A foot-bridge breaks the river, sculpted from pale wood: the only person-made thing visible for what feels like miles around. Enclosed by mountains, I am overwhelmed by the illusion of remoteness. My head begins to ache again.

We did not find the swamp as delightful on acquaintance as it looked from a distance. It is composed of moss piled layer on layer into which you sink knee deep if you make a false step, and then there is nothing for it but to sit down on a tuft of grass and pull out one or both feet as the case may be. […] Imagine the fatigue of pounding away at such a rate, my head throbbed painfully…

The Ahukawakawa swap is moss upon moss – composed of sphagnum or, more commonly, peat moss. The swamp was formed 3,5000 years ago and is an exciting place for botanists (my partner). It is an alpine swamp (sitting at 920 metres), which means that the mosses and native grasses survive at extremely cold temperatures. Beneath the boardwalk, the ground is porous. It takes us half an hour to cross the swamp, walking over ancient lava beds; I imagine it took Frances’ party much longer. At around 7.30am we exit the swamp and reach the Holly hut, which is sheltered by a ring of scrubby Manuka. A dry stream bed separates it from the main track – we would have missed the turn off if I had not been walking so slowly. We eat a hard-boiled egg each and boil water for coffee. The ground is cold and damp, not yet warmed by the sun. Several groups of hikers are getting ready to leave, walking the track in the opposite direction: they have a steep climb ahead. After breakfast, we re-join the main track. The landscape changes as we ascend. Red and orange clay, yellow ranunculus, windswept trees. Prehistoric lava flows have made dramatic clefts in the mountain-side. The dry bark and warm earth tones remind me of Australia, our geology once joined at the hip. There are no ferns here, few flowers and no berries. The track continues to climb.

We reach the top of the ridge before 9am and gaze out over a sea of trees, small islands of volcanic rock. I am ready for the downhill, until I turn and see the track cut into the mountain, a narrow line dividing its body in two. There is a long way to go. As we meet Taranaki, the well-maintained track disappears, replaced by a narrow path scattered with roots and loose rocks. Parts of it are completely obscured by vegetation. Soon the vegetation is replaced by scoria and scree and the memory of rock-fall is visible above and below us: my stomach tightens every time I look down. In some parts, the path has crumbled and we must climb over large andesite boulders. I am terrified as I feel the scoria move under my feet. Camera abandoned, I cling to the side of the mountain. After an eternity, we pass the scree slopes and enter the cloud cover. Damp, dark and green.

Then upward, onward, over loose scoria. It was a case of three steps forward and two back. I held on tightly to two sticks which were held one by the guide, the other by Mr G; in this way we reached the top. Coad said, “we will just go up, turn round and come down again.” But I begged for a quarter of an hour to rest and sank down tired out within a few yards of the first snow I had ever been close to. I contented myself with looking down upon it and marvelled that that which looked like a tiny speck from below should cover so large a space.

I think of Frances summiting Taranaki – how? Even half-way up the mountain feels too high, almost dangerous. Cole powers ahead but the height has thrown me off balance. My legs shake and my head is clouded with vertigo. I am grateful that I cannot see how high we are. Suddenly the track plateaus and the cloud breaks: we are standing on the promontory of the ridgeline, a rock jutting out into space. There is some more loose scoria, the earth shifting beneath my feet, and then suddenly we are back in the tree-line. We can hear the voices of other hikers now, day-walkers in the national park. Soon we meet young families, women with picnic baskets and teenagers in jeans. It is strange to realise that we were not so high after all: in my fear, everything felt so far away. As I think back over the last two days, the landscape, the archive and two sisters merge into one moment – a single mutating archive. Our photographs, Frances’ sketches. My voice in the camera, saying her name.

…and I recall with pleasure the quarter of an hour spent 8400 feet above the level of the sea