By Michele Leggott

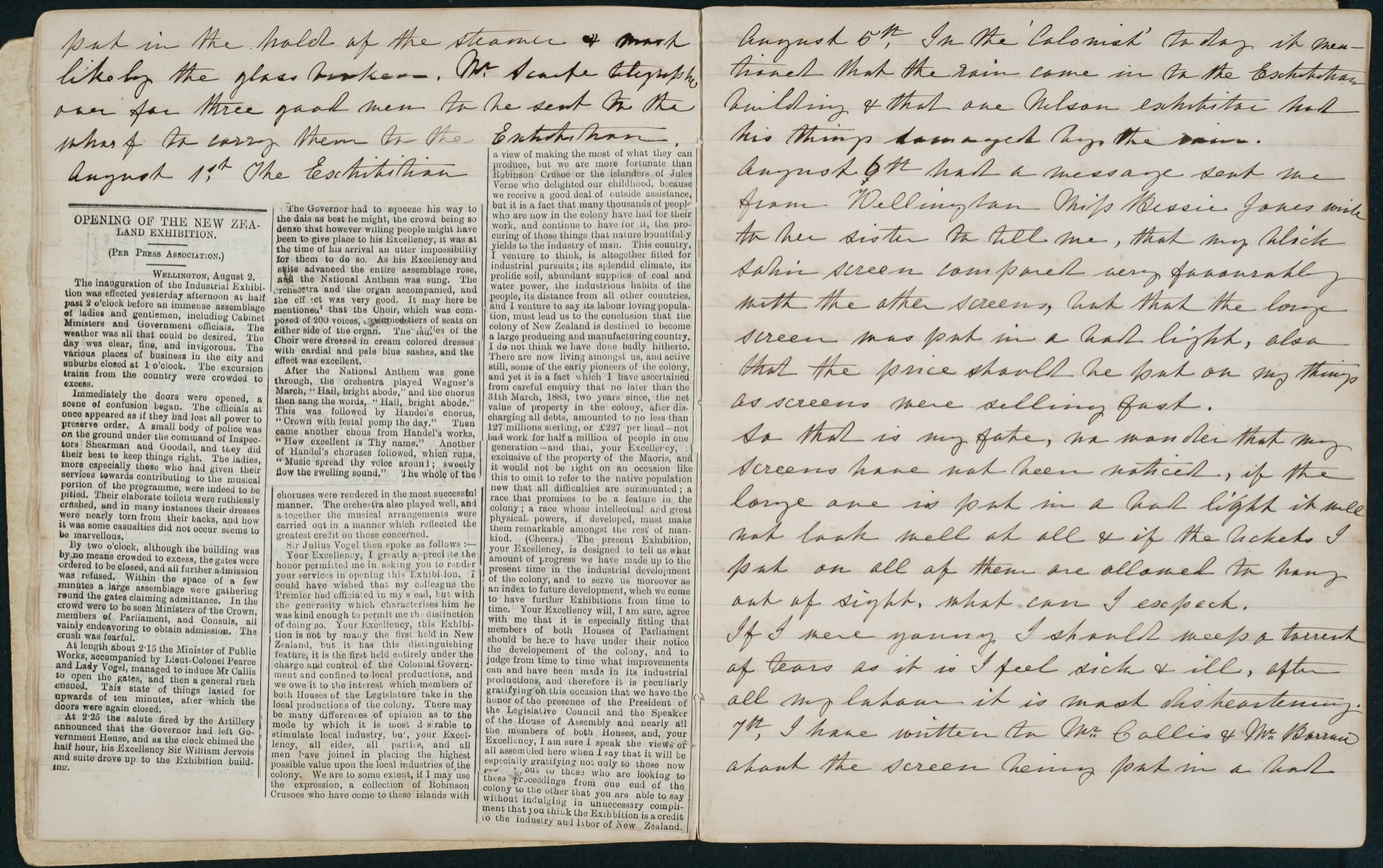

Drawing Lines is the title we’ve given to our full transcription of Emily Harris’s diaries 1885-1891, to point out a connection with Writing Lines, the section devoted to Emily’s letters and diary excerpts 1860-1863. In 1860, Emily at 23 was an accomplished writer of lively prose and two fascinating poems, sole remnants of her poetic output from the period. By 1885 she was focused on her art but it is clear from the diaries that she continued to write poems and to show them to family and some trusted friends. We may not have Emily Harris poems from the 1880s but her diaries deliver a vivid account of how difficult it was for a single woman of slender means to fulfil her creative potential. They are a delight to read and build a detailed picture of life in Nelson in the later years of what came to be known as the country’s long depression. Money is scant in the Harris family. Edwin’s three unmarried daughters teach dancing, music and drawing as well as running their small private school for local children. There is no domestic help and Emily often laments the lack of time for focusing on her own drawing and painting. Despite this she manages to send work to national and international exhibitions and to publish her three lithograph books New Zealand Flowers, New Zealand Berries and New Zealand Ferns in 1890. To remedy the family’s ailing finances, she also organises exhibitions of work by herself, Frances, Ellen and Edwin, selling to local audiences in Nelson, New Plymouth, Stratford and Wellington.

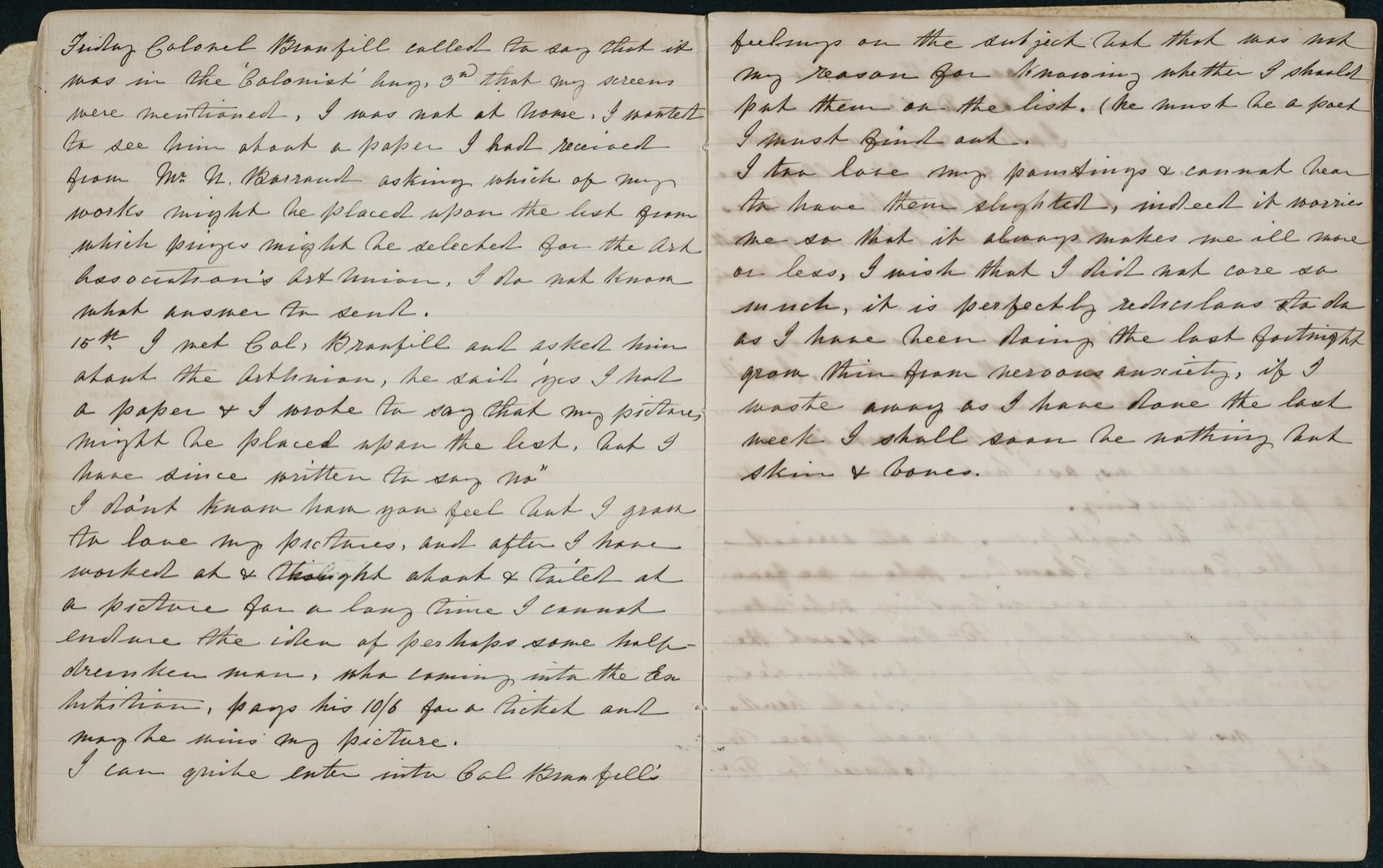

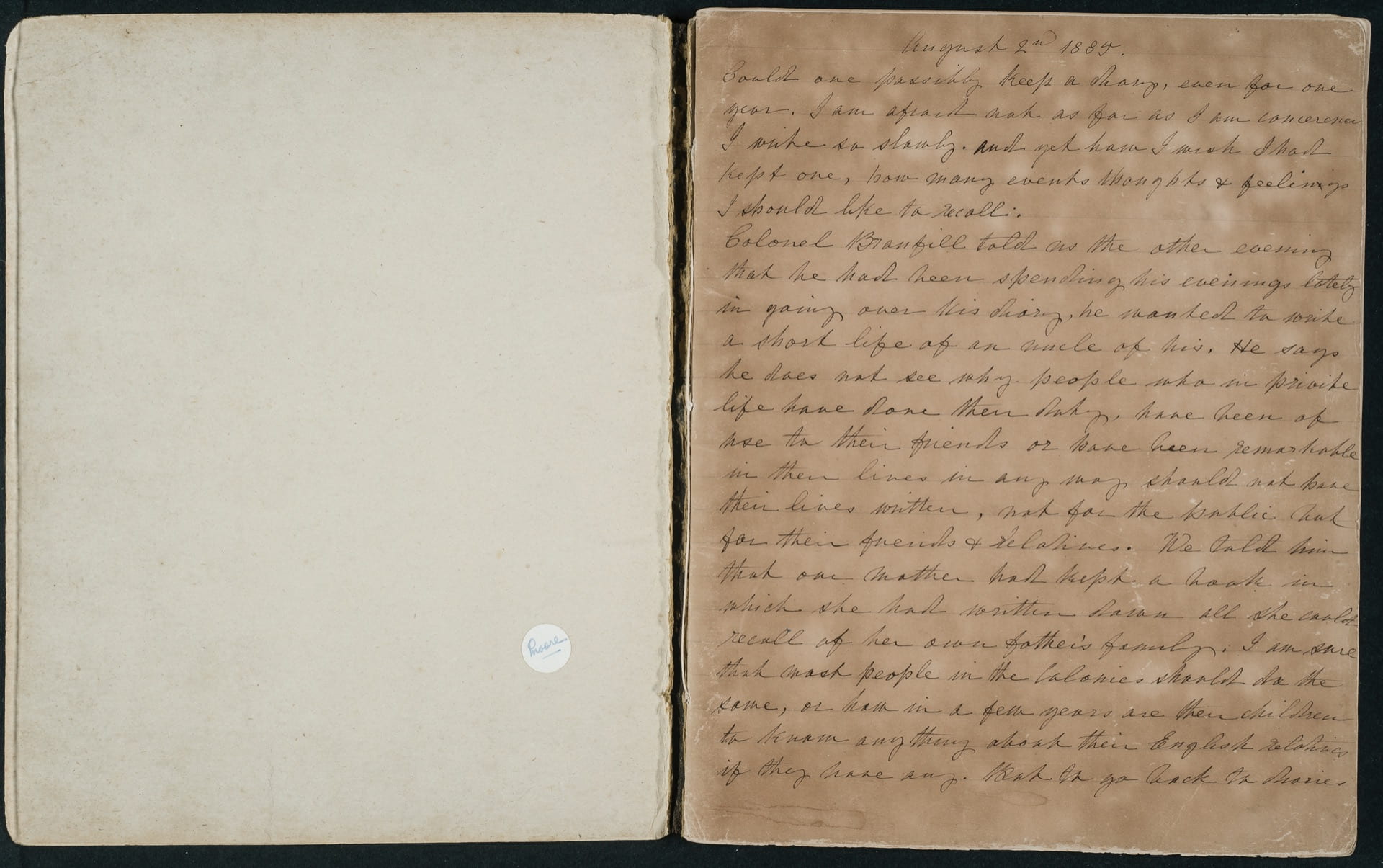

The diaries give close coverage of the day to day difficulties and pleasures associated with independent art making. They also feature passages in which Emily writes up particular events as set pieces within the general fabric and it is at such points that we see Emily Harris the writer emerge and flourish in the pages of her diary. Some of our favourite moments in Emily’s writing occur when she has the time to give her diary full descriptive attention, for example in the engaging opening she makes in August 1885:

Could one possibly keep a diary, even for one year. I am afraid not as far as I am concerned. I write so slowly and yet how I wish I had kept one, how many events thoughts and feelings I should like to recall.

[…]

Well, long ago, some seven & twenty years, in the days of my youth, what an age ago! And yet now I seem to be just beginning to find out what I can do, & how to do it. If I could only have had the advantages then that young people have now, instead of groping in the dark & longing for what we know not, what a different career would have been mine. Oh that diary, begun when I was young and life was all before me. I wish I had gone on with it, if only for a few years, what a true record it would have been of a colonial girl’s life with romance enough for more than one novel, what a graphic account of the Maori War, what we did & suffered & went through in those days. But to return to the diary.

It was before the War, when we lived in the forest. I used to write down all I did, where I went, what people I met and what they said to me, sometimes I wrote the stories people told as we sat round the fire. One day my mother got hold of my diary, she went into her room & for hours read it to my father. I heard them laughing very much; one of my sisters [told] me what they were reading. I was in a great rage, and as soon as I could get the book put it into the fire, alas! My mother not knowing what I had done told me how very much pleased she was with what I had written, only she wished to point out how I might do better in future & that I must be very careful how I wrote about other people. She was very much vexed when she found what I had done & also that I would not go on with the diary.

And now after all these years I commence again, just to trace if I can the fate of my latest work, a four-fold screen upon which I have been working for some months.

Other standouts in the diaries include an account of saving precious family letters from England when Edwin went on a burning spree in 1886 (Emily distracted her father and tucked the bundles of letters into the folds of her dress and her apron). Among longer pieces is the account of the camping out party beyond Happy Valley at Christmas-New Year 1888-89 (‘My first feeling when I returned home was that I could not endure to live in a house’). Then there is the drama of helping to save a friend’s house during an out of control burn-off in Inglewood, Taranaki, in February 1890:

In an instant I was out of bed & we dressed as fast as possible. Suddenly our room became as bright as day. The forest was crackling & burning, the wind was raging & driving showers of sparks & flame towards the town.

We hastened into the yard & found Mrs Curtis & the servant girl pumping up water as fast as they could. We set to work at once to carry buckets of water, to fill everything that would hold water. We both took twenty buckets, the washing tubs a great many. Then we went into the store and got piles of buckets & dippers, the buckets we filled with water and placed at intervals round the buildings with a dipper to each.

Finally, there is Emily’s day by day account of her Wellington exhibition of October 1890. So much hard work went into the preparation and running of the show at Baker Brothers Auctioneers on Lambton Quay. So many friends supported the show and still it was not enough to do more than make ends meet (‘The fact is I ought to have been here three months to work the thing up, or else advertise largely, which was too expensive.’). But it is in adversity that Emily Harris shines and the diaries are testimony to her courage and perseverance. She always comes through a crisis and pulls from the experience something to write home about:

As I mentioned in the last letter I might have been in better spirits if I had not been so dreadfully tired, so much walking and standing about made my legs ache so, I could scarcely stand sometimes. People were most kind & if I could have stayed longer no doubt I should have enjoyed myself very much, I had to refuse invitations.

I went again to the Kirks’, spent nearly all day sketching rare flowers in Mr Kirk’s study & from his garden. I went several times to the Atkinsons’, dined & had tea there. One day Lady Atkinson took me for a drive on the Karori Road, the country looked lovely & Wellington did not seem such a narrow strip after seeing the miles of country at the back of it.

We have divided Emily’s diaries into 12 sections and supplied contextual notes for each section that broaden the range of voices contributing to Emily’s narrative. A short introduction and summary of diary content is available, along with a bibliography and an index of names.