By Michele Leggott

There are just ten surviving poems by Emily Harris, two from 1860 and eight from the 1890s or early 1900s. They are the visible tip of a writing practice that persisted from the time Emily was a young woman in Taranaki, teaching in her mother’s school before the war, to her later years as an accomplished botanical artist in Nelson. We can’t be sure she wrote continuously through this time but there is evidence from both the earlier and later years that writing poetry was important to Emily and that she moved to preserve some of it for readers in and beyond her circle of friends and family in Nelson and New Plymouth. Let’s take a look at some of the ten poems and Emily’s commentary on the writing of poetry early and late in her life.

We can start with the poems of 1860, one written into a diary entry of 11 September and showing a talent for topical satire, the other a veiled elegy for Emily’s brother Corbyn, killed on the beach at Waitara 28 July that year. Emily presents both poems in context:

Letters, Scraps of Diary &c beginning about six months after the first Maori War commenced in Taranaki

September 10th 1860

Today an Expedition went to the Waitara with the intention of destroying Wiremu Kingi’s pa in the bush. They started from the town at 12 o’clock, upwards of a thousand men (1400) besides a large party of Volunteers and the mounted Escort. There were nearly fifty carts with luggage and four cannon. I saw them all pass, not all in one body, two strong detachments went first then the carts then another strong body and lastly the Volunteers who are mostly young men and seemed in good spirits. God grant that they may all return again in safety.

General Pratt went to take command of the force, with his evil genius Col. Carey. I think they had better have remained here and entrusted it to Major Nelson.

Sept 11th A poor woman, Mrs Miles, died of fever (another victim of this ill-fated war). Mr Leech was buried this afternoon, how very depressing so many deaths.

About six o’clock hearing an unusual stir in the street I looked out of the window and to my surprise found that the mounted Escort had returned. The troops are to return tomorrow covered with laurels from having achieved the glorious feat of attacking and destroying an empty pa. They were fired upon by Natives in ambush, one of the 40th soldiers was killed and five wounded. The fire was warmly returned and the Maories [Māori] dispersed. So tomorrow General Pratt returns in order to celebrate this important victory and to allow his men some repose after their long campaign. I must scribble a few lines in anticipation.

Come cast all gloomy cares away

Wear nought but smiles this festive day

Let garlands gay adorn the street

And loud acclaim the soldiers greet

Quick beat the drums,

Behold the conquering hero comes

Another such a victory won

Another such achievement done

And we may to our homes return

And empty pas for pastime burn.

Sept 12th Very wet. The soldiers returned in pretty much the same order in which they went except that they gave a loud hurra as they entered the town and some sang snatches of warlike songs, a great deal they have to be proud of, it is even asserted that some ran away; at any rate they left the dead body of their comrade to be mutilated by the Natives. (Writing Lines 1)

So off I went straight for the dell, Capt. Miller followed. I had often [been] warned [by] Mr Des Voeux not to go into the dell, for fifty Natives might be in ambush there, but now all thought of danger had flown. I went on very quickly because I wanted to go all over it. Picking a flower here and there making a few remarks and lamenting the weeds that had grown so high, we came to one small open space, in the middle of which grew a pink hawthorn in full bloom. I had often seen the tree but not the flower, my exclamations of surprise and delight and efforts to reach the blossom made my companion smile, he got some of the flowers for me, we stayed a few minutes it was a lovely spot, beautiful ferns and native shrubs growing all round. You should have brought a pencil and paper and written some lines here, he said. Strange to have said that to me, I believe I was at that time the only girl in all Taranaki who ever wrote a line.

I did write some verses in the evening but never showed them to him.

Lines Written on Visiting Glenavon during

the War 1860.

Oh! I could sit and gaze for hours,

Musing alone

Upon thy lovely blooming flowers

Dreaming that fairies in their bowers

First tinted them.

Or on that tiny winding stream

O’er grown with weeds

That erst would gaily flash and gleam

Like silver neath the golden beam

Of summer’s sun.

Or upward turn my wondering eye

Above the trees,

To watch the gauzy clouds float by

A snowy veil athwart a sky

Of deepest blue.

But now my stay so short so brief

I may not pause,

To linger o’er one bud or leaf

Or twine one fair or fragrant wreath

With thy sweet flowers.

One rapid glance around me cast

Noting the trace

Of River’s step I onward passed

With painful thought that t’were the last

For years perchance.

Sweet Peace we little knew how dear

Thou wert to us.

Until we mark’d the widow’s tear

And saw extended on his bier

One gone for ever.

Oh! we may learn to wear a smile

And heedless laugh

Twill but the careless eye beguile

For still we feel beneath the wile

A mournful heart

One hour can loosen War’s red hands

And set him free

But grey exiles in many lands,

Can tell how hard to clasp the bands

Strife once has severed.

Even as we read these poems from 1860 we are aware that Emily is copying them at a later time, perhaps for her New Plymouth nieces Constance and Ruth Moore in whose papers they were found. Emily wants to preserve letters, diary excerpts and poems from her wartime experience. In doing so she discloses in passing the importance of her poetry, writing to her mother Sarah in Nelson 4 February 1861:

I should like to hear of the safe arrival of the box I sent before I venture to send anything again. In the box is a letter and some verses of mine which I should like to have returned as I have not even time to copy or even to write out correctly. (Writing Lines 7)

Two decades later Emily’s diaries supply tantalising glimpses of her poetry writing. At one point, 28 April 1889, we learn that New Zealand Flowers, New Zealand Berries and New Zealand Ferns were to have been published with what sounds like poetic epigraphs: ‘I have got two poems ready for two books, but I do not get on with the illustrations.’ (Drawing Lines 8). But it is a diary entry of 7 August 1885 that reveals the existence (though not the texts) of a body of Emily’s poems.

Ellen & I had today letters from the Rev. J. Taylor D. D.; in mine Dr Taylor says, ‘Many thanks for the verses which I shall prize as a souvenir. I really regret that I did not know you personally better while I was in Nelson. It was only at the very last that I knew you as I now remember with pleasure, & regret too. Had you been trained to write in earlier days you would have done well & been able to earn by your pen an honourable income & position.’

And so he, a clever man, has come to that conclusion. It makes me very sad to think how my life has been wasted. Why could I not have met a Dr Taylor before, to help, direct & encourage me. (Drawing Lines 1)

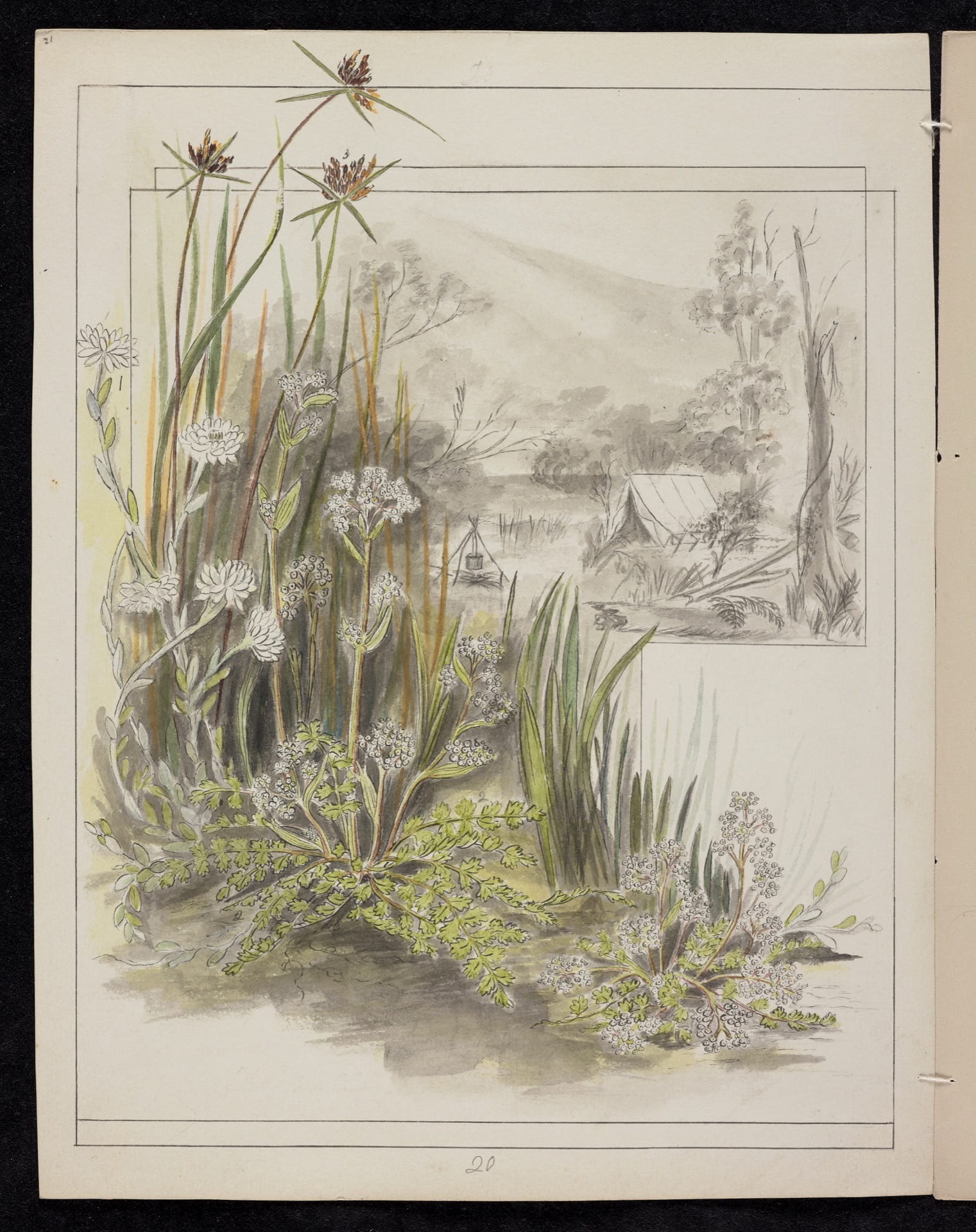

To judge by her 1889 remark about having poems for the books of botanical drawings, Emily recovered from her disappointment at the hands of Reverend James Taylor sufficiently to keep on writing poetry. The artist’s book New Zealand Mountain Flora contains the eight short poems that make up the balance of her poetic oeuvre. Unlike the poems from 1860, the Mountain Flora texts are typed. They accompany Emily’s notes on the flora, also typed and pasted into the book opposite the plants they describe. We don’t know who typed the poems and botanical notes, but a good guess would be a young friend or one of Emily’s nieces, readying Mountain Flora for twentierh-century publication. That publication did not eventuate and the watercolours and poems of New Zealand Mountain Flora remained in the archive until our website publication of texts and images this year. The poems range from descriptions of specific flowers (‘The Edelweiss,’ ‘The Spear-grass,’ ‘Snow-berries’) to meditations on alpine landscape and human impact on fragile ecosystems, as in the untitled poems #3 and #6:

The mountain looks down on the river,

And the river flows on to the sea

In their grandeur and beauty for ever

As long as this planet shall be.

But the forest that grew by the river,

And the flowers on the mountain that bloomed

Will they gladden our hearts for ever

Or pass like a race that is doomed?

Let us camp on the hill-side

The valley below

The mountains afar

With their clouds and their snow.

The blue sky above us

The stream flowing near

With our pipe and our dog,

And our comrade so dear.

We’ll dream that the way

Unto Paradise lies

Where yonder green hill

Meets the clear shining skies.

What happened to Emily Harris’s poems? The family were great preservers of their written and artistic heritage and yet there is no sign of the poems apart from these few fortuitous appearances in a copied manuscript and a book. that was not published in Emily’s lifetime. The poems have disappeared, but it is still possible to imagine that other documents will be discovered and give context to Emily’s poetry. One such document is Emily’s notes on her sister Frances, written 12 June 1898 and slipped into the illustrated journal Frances made of her ascent of Mount Taranaki in 1879. Emily’s notes provide invaluable glimpses of the Harris household in the 1840s and 50s:

The forest was our playground, we knew every berry & flower – But it was not all play by any means. We children had to work very hard in the house, taking the different work by turns. Also we had to try (encouraged by our dear mother) to educate ourselves but it was not easy work with so many interruptions. Had we known what kind of life was before us we could have done more, I might have & Frances also. […] When I think how deeply she regretted and with cause her want of education in after years, the more I lament how her life was spoilt for the want of the opportunity.

I must pass over years, and write the first letter I can find. We were very fond of poetry, and used to learn a great deal to recite to each other, never to other people, we were too shy for that. Someone offered Frances half a crown if she would learn the Curfew in a very short stated time, which she did. (A Wonderful Panorama)

Thomas Gray’s ‘Elegy in a country churchyard’ (1751) begins ‘The curfew tolls the knell of parting day’ and is still a staple of English poetry. It joins other favourites by William Cowper, Felicia Hemans and Alfred Lord Tennyson quoted by Emily and Frances as templates for their experience of colonial society and the New Zealand landscape. If more of Emily’s poetry comes to light, we can expect to hear in it echoes of the British and American poets Whose work nineteenth-century readers carried with them as recitation as well as text.

We are preparing a section called ‘The Poems’ that will feature all ten of Emily Harris’s poems and a selection of poetry from Taranaki written between 1840 and 1869. Coming soon in July.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott