By Michele Leggott and Catherine Field-Dodgson

The reporter from the Nelson Evening Mail is more than usually enthusiastic about the work on show at Emily Harris’s studio in Nile St East. Under the heading ‘Some Exquisite Paintings’ the range and ambition of Emily’s latest project is described in detail:

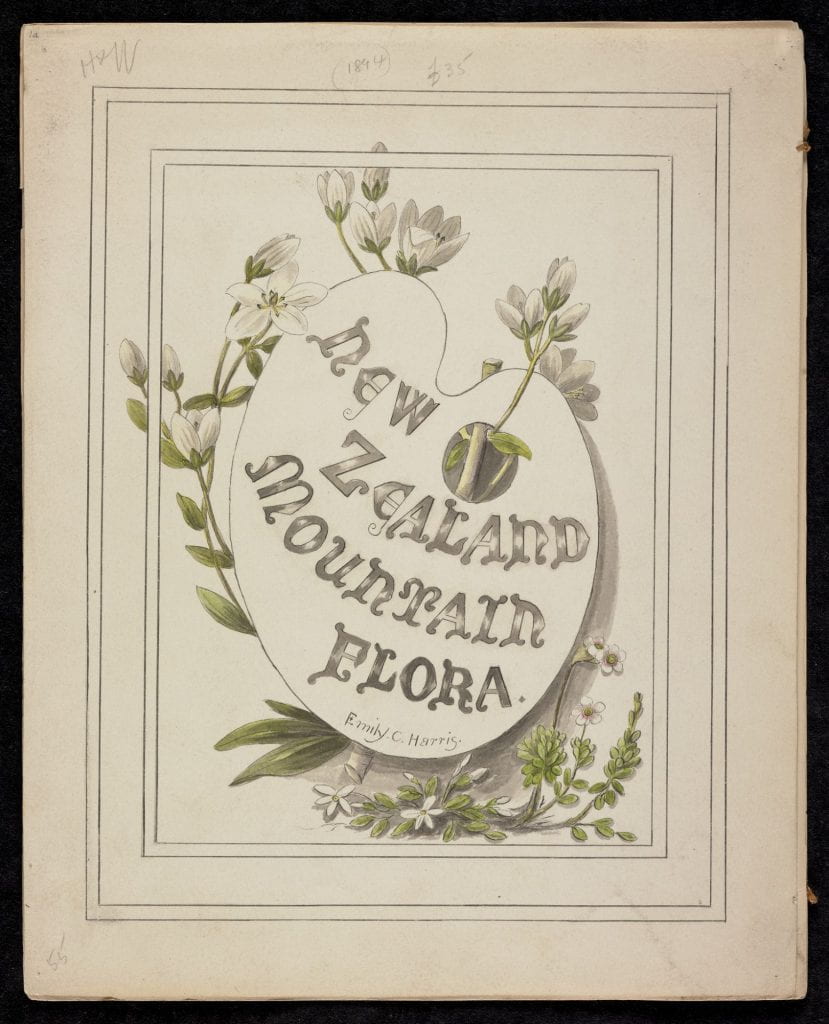

Miss Harris has undoubted talent in depicting to the life the exquisite hues of the innumerable wild flowers of New Zealand, more especially those that grow high on the mountains of the south, and in these her life-like fidelity amounts almost to genius. One needs but to inspect the group of lovely blue ‘Pleurophylla speciosa’ which grows in Adams’ Island, brilliantly coloured ‘Golden Lillies,’ and ‘[Ligustica]’ to fully appreciate the wonderful gift of beauty bestowed on this country by Nature in her most lavish mood. Miss Harris is endeavouring to publish a book of paintings illustrating the mountain flowers of New Zealand. Botanists have written about the endless variety of these flowers ; but their works have lacked illustration, or if the flowers have been depicted, they have not been painted when in their natural state. Miss Harris paints direct from nature, brings out every important feature as only an artist can, and so adds a useful work to the botanical library of New Zealand. But, apart from the scientific value of the work, it should be a most beautiful and interesting acquisition to drawing-room or study. The book will comprise some 36 pictures in water colours, and judging by those already accomplished, more especially the Mount Cook lilies and the frontispiece, (her work will be of great value, without considering the fact that it is the first of its sort to be published in the colony. Miss Harris requires 200 subscribers, and, for the purpose of enrolling members, the work, so far as it is completed, will be on view in Mr Ambrose Moore’s office for the next few days.

After mentioning Emily’s upcoming exhibition in New Plymouth, the reporter recommends a personal inspection of the studio in order to fully comprehend the artist’s achievement:

There are numerous studies of the clematis under different conditions, rangiora, cabbage-tree blossoms, snow berries, gentians, sprays of geum, orchids of various kinds, manuka — a clever piece of work— kowharawhara, edelweiss, whau, cordyline berries and flower-, all in endless profusion, on the walls, on easels, and on the door, with a variety of which the eye never wearies. One picture— on a plaque represents a spray of rata, which it is hard to believe at first sight is not real, so perfect is its perspective, so minute its fidelity to nature – line for line, and colour for colour. Miss Harris should seek a larger field than New Zealand for the disposal of her life-work— no less a field, in fact, than the British Museum. (Nelson Evening Mail, 9 Mar 1899: 2)

But Emily Harris is well ahead of the newspaper reporter in her bid to attract the attention of the Botany Department of the British Museum. In 1894 she packaged up and sent to London a set of her lithograph books New Zealand Flowers, Berries and Ferns (1890), three original watercolours and a letter introducing herself and her interests. The Botany Department was being offered samples of her work on native flora both typical (the 36 uncoloured plates of the books) and on the rare alpine plants that were absorbing her attention long before 1899. Being the careful artist she was, Emily made sure the three paintings sent to London were copied and so it is that each has its twin in the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington.

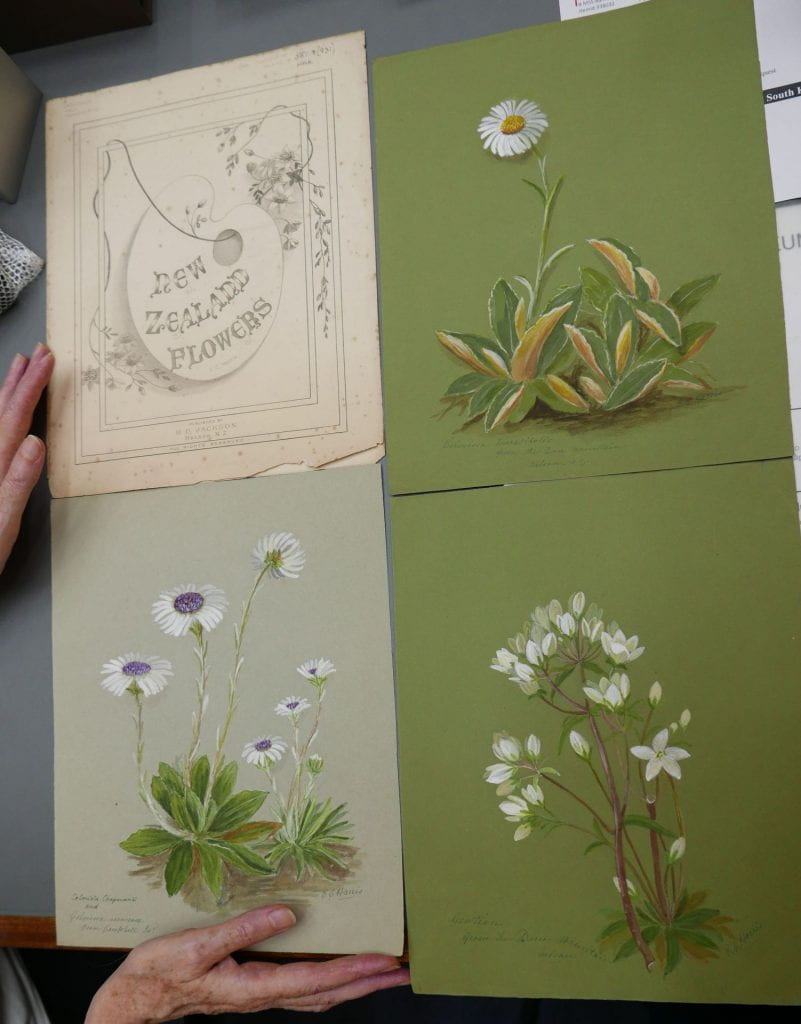

The three pairs are worth looking at in some detail. In 2019 we saw the London versions at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington, exactly where they arrived in 1894 and still in perfect condition. NHM was for many years a division of the British Museum. It was a surprise to find Emily had preserved the three paintings in a discarded New Zealand Flowers cover and explains why the NHM cataloguers assumed they were part of a collection published in that year. The cataloguers, also describe the paintings as bodycolours. Bodycolour is water-based but is more opaque than watercolour in order to show colour on a non-white ground.

When we examined the Turnbull versions we were struck by their similarity to the NHM paintings, which are in each case smaller, presumably to fit the cover in which they travelled to London. Here is the first pair, Emily’s representation of an important botanical find at Campbell Island in 1890:

Right: Emily Cumming Harris, Celmisia chapmanii (Campbell Island). Celmisia vernicosa – Campbell Island. [1890s?]. Watercolour on grey paper, 310 x 440 mm. Turnbull. C-023-018.

the largest (Miss Harris says in a letter)

but the letter has disappeared from the archives at the Natural History Museum and we must make what we can of the other works it would have described to the British curators. Here they are, each with its Turnbull twin, each pointing at the other and registering small differences of nomenclature and location:

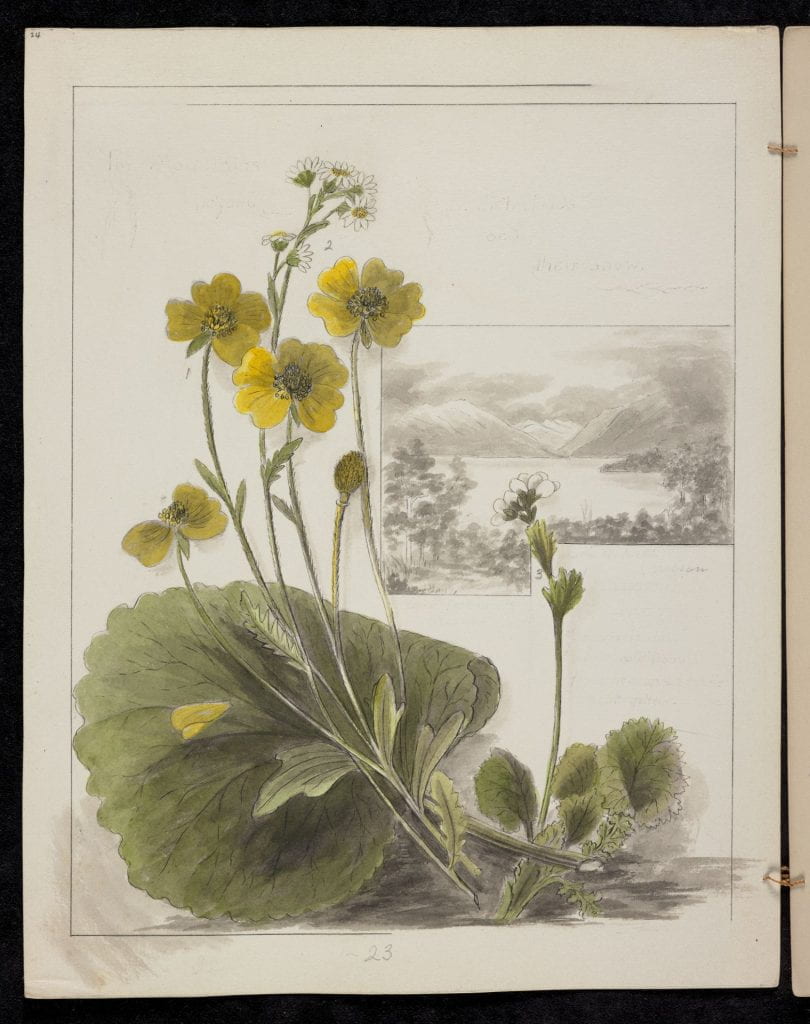

Right: Emily Cumming Harris, Celmisia hieracifolia (?Mt Egmont). Undated. Watercolour on buff paper, 340 x 490mm. Turnbull. C-023-004.

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/23156178

The NHM celmisia is vibrant against its olive green ground, especially the white of its petals and the gold undersides of the leaves. The painting is compositionally identical to its Turnbull equivalent despite the discrepancy of locations. Emily has painted the same plant twice, once in landscape format, once in portrait. We turn to the final pair:

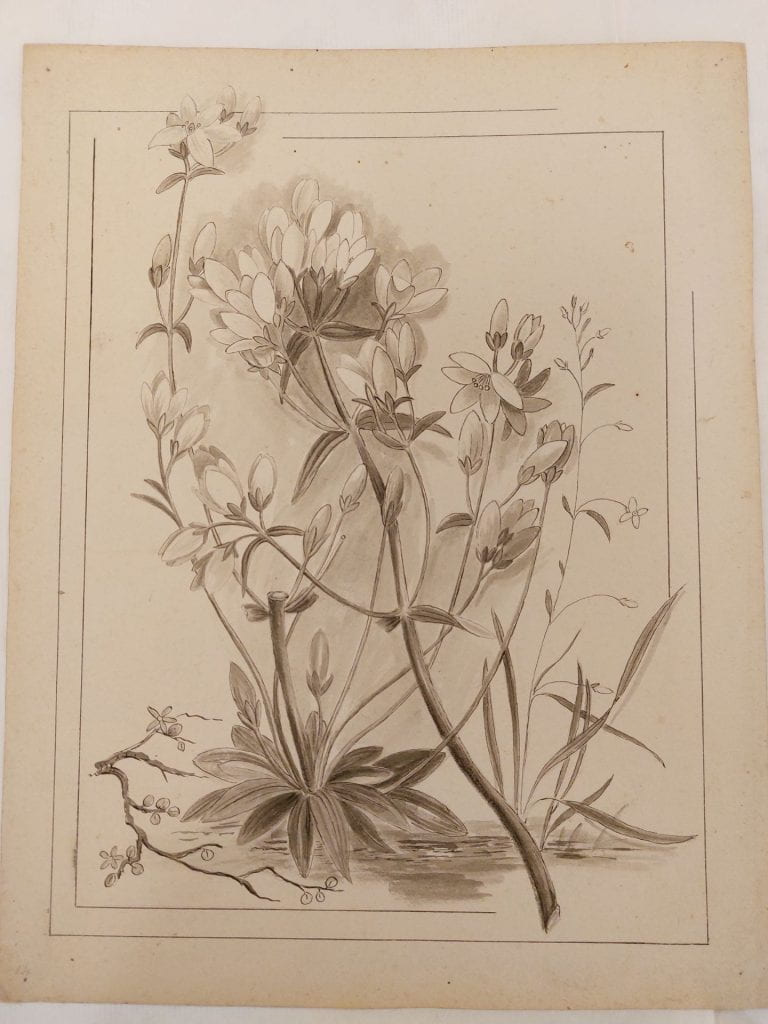

This time both versions are on greenish-coloured paper and in each case the white gentian petals are almost translucent against their dark ground. Again Emily has painted the same plant and the same composition, so we can attribute a Dun Mountain location to the NHM painting and perhaps a species name.

What makes these plants special enough to send representations of them to London? In the absence of Emily’s letter of explanation we could start by consulting the relevant authorities. First, Sir Joseph Hooker and Thomas Cheeseman on celmisias:

CELMISIA. Cass, A most beautiful genus, abundant in New Zealand, and, as in all the other large genera of these islands, the species are very variable, difficult to discriminate, and intermediate forms may be expected between those here described. (Hooker, Handbook of the New Zealand Flora 1867: 129)

The genus Celmisia, which is confined to New Zealand, with the exception of one species found in Australia and Tasmania, forms one of the chief ornaments of the montane and alpine flora of the colony, the various species usually composing a large proportion of the vegetation, especially in the South Island, where the mountain slopes and valleys are often whitened for miles from the abundance of their large daisy-like flowers. With few exceptions, the species are exceedingly variable and difficult of discrimination. (Cheeseman, Manual of the New Zealand Flora, 1906: 297)

Then there is Thomas Kirk on mountain gentians in 1894:

While fully admitting that all the New Zealand species are closely related to G. montana, long-continued observation of these plants in the recent state has convinced me that they may be distinguished without any great amount of difficulty. […] Bearing in mind the extreme rarity of white-flowered gentians in other countries, it is remarkable that all the local species primarily produce white flowers, although G. antipoda, G. cerina, and G. antarctica var. imbricata exhibit also various shades of red, purple, and violet, or occasionally white with vertical streaks of red: the other species are pure-white. (Transactions Vol 27 1894: 330-31)

Looking over Emily Harris’s shoulder as she composes her letter to the Keeper of Botany, we can assume she will note not only the size and beauty of the Campbell island celmisias but the appearance of their mainland cousins in her own district, along with a gentian that would be blue or purple in other parts of the world. The paintings at the Natural History Museum and the Turnbull Library testify to her intentions: she is presenting visual documentation of three species endemic to New Zealand, all three with spectacular white flowers.

& yet now I am quite ready to go again.

Thomas Kirk supplied Emily with specimens of celmisia from distant Campbell Island. But how did she come by the Dun Mountain celmisia and gentian? Again we might look over her shoulder and guess at what is going into the letter as she comes to her local specimens. Given the proximity of Dun Mountain to Nelson city and her familiarity with its plants and flowers, it is quite possible that Emily collected them herself. Her diary for 1886 refers to several day trips to the nearby mountain:

We had a few weeks ago a picnic up the Dunne Mountain tramway. I took a sketch from there of Nelson, that & the nikaus I have since finished. (24 March)

I went with Mrs Buckeridge & her three sons & a few others for a picnic up the Dunne Mountain line just above the Glen. (24 May)

We gave ourselves one holiday, I got up a picnic to get some clematis, our party consisted of Mrs S. B. White, Miss Branfill, Clara Wright, Myra Mabin, Frances & self. I almost forgot Lily Burton. The ladies were to go at eleven a.m. & the gentlemen to follow at two p.m. as they could not come before. They were Mr Redgrave, Mr Worsley, Mr F. Smith, Emerson Mabin & Lee Buckeridge. F. Smith came in the morning to say that as he could not come to carry the billy he would send a carriage to take it as far as the foot of the Spur, so he sent one that held us all. It made the day much more enjoyable as we were not so fatigued as at other times. (17 October)

The exertion of climbing and botanising in corsets and long skirts suffuses Emily’s account of a more challenging trip the following month from which the ladies of the company came away with a large haul of local flora:

On the 9th of November we had a very enjoyable picnic. Mr Smith & Mr Worsley sent their cabs for the ladies & baskets, both going & returning to the Glen. Those two seemed to have put their heads together to think of everything they possibly could. One evening they came in to say that we were not to take any milk because they had engaged a dairy to supply us with milk & cream. We had our lunch at the Glen, then most of us climbed up the Bullock’s Spur onto the Tram Line. One young lady had never climbed a hill in her life before. She afterwards said she had never enjoyed a picnic so much.

Lillie Burton, Mr Redgrave, Mr Worsley & I climbed up to the top of the Fringe Hill, it was very steep. Lillie got on famously but I had to rest every three or four minutes. I felt as if I could hardly breathe & my legs ached so I could not move, but after a little rest I was always able to go on again. Long before we reached the top the view was lovely & extensive. There were lots of tiny wild flowers all the way up but near the top was a great deal of moss, with little white violets growing up between the short green moss. On the top the trees, shrubs & ferns were very beautiful. I hope they will never be destroyed by man or any other animal.

Mr Worsley found another way down, a longer but more gentle descent, a lovely pathway through the manuka, grass & shrubs. He was quite laden with all the treasures we had gathered. He said he hardly knew which it would be best to take, what we had picked or the top of the Fringe itself.

Coming down for a short way it was rather steep & the wind was blowing so we could hardly stand. I had had face-ache for nearly ten days & I kept wondering whether it would make it worse. But instead it blew it all away completely & I have not had it since. I was very tired for days after & yet now I am quite ready to go again. (9 November)

This is the Emily Harris who writes at the end of a Christmas-New Year camping out trip: ‘My first feeling when I returned home was that I could not endure to live in a house.’ (9 Jan 1889) As E.C. Harris she will let the readers of her New Zealand Mountain Flora preface know how closely she engages with botanical groundwork: ‘I have camped on the Dun Mountain line and found many interesting plants on and near the mineral belt. Also at a lovely mountain lake where Alpine Flora abounded.’

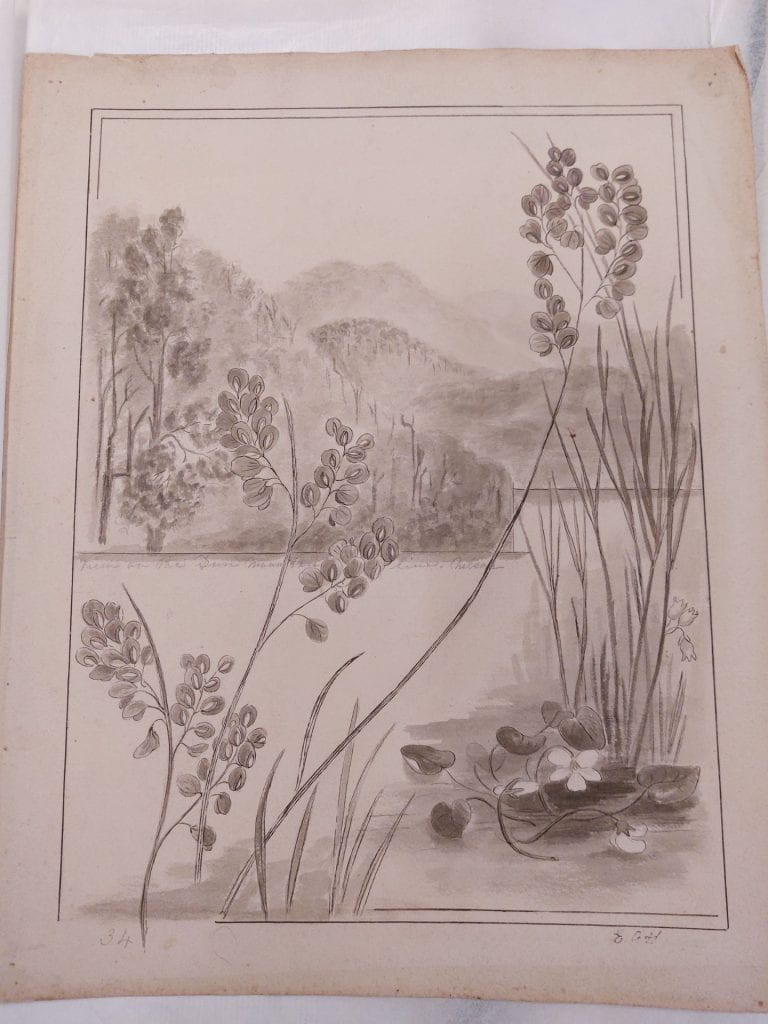

The alpine lake is Rotoiti, southwest of Nelson. Trawling through Emily’s works we find lakeside renditions of Gaya Lyalli (houhere), Geum Magellanicum, Ranunculus insignis (korikori, Senecio lautus (shore groundsel) and Geum albiflorum (white-flowering avens).

And there is the more immediate question of a sponsoring authority for the two white flowers she is bringing forward from her own locality. Who will vouch for her Dun Mountain Celmisia hieraciifolia and Gentian gentiana?

the scientific gentlemen again

In 1894 Thomas Kirk was excited about developments in the identification of both gentians and celmisias in the Nelson region. He read a paper entitled ‘A Revision of the New Zealand Gentians’ before the Wellington Philosophical Society, 28 November, 1894, noting a new species Gentianella corymbifera, found in the mountains of Nelson and Canterbury. He sent another paper, ‘On New Forms of Celmisia, Cass.’ to Robert Kingsley to be read before the Nelson Philosophical Society 10 December 1894. The new forms centred around discoveries made at Mount Stokes in the Marlborough Sounds by young botanist Joseph McMahon. Specimens of the new celmisias and gentians are present in Kirk’s collection at Te Papa and in the herbarium at Kew but none reference Dun Mountain as a collecting locality and so cannot be the plants Emily Harris painted.

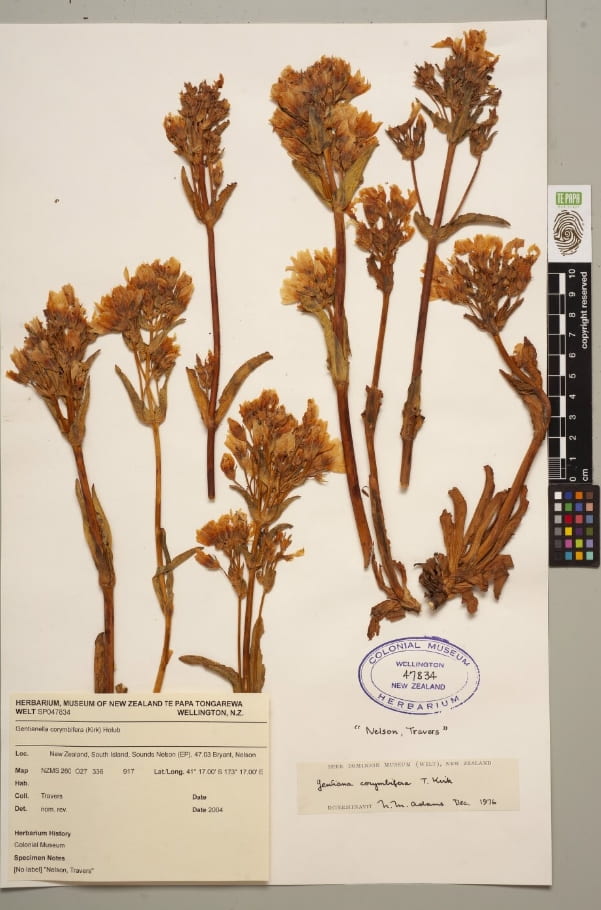

Enter Henry Hammersley Travers, a Nelsonian resident in Wellington and well-known naturalist son of William Thomas Locke Travers with whom as a boy he explored the mountains of Nelson, Marlborough and Canterbury. Like Kirk, Travers was a Fellow of the Linnaean Society (FLS) of London. He was with Kirk on the Hinemoa voyage to the sub-antarctic islands in January 1890, collecting birds rather than botanising, but he was distinguished in both fields. Among Kirk’s Te Papa specimens is a Celmisia hieraciifolia collected on Dun Mountain by Travers at an unspecified date and cited in Hooker:

Another Travers specimen from Nelson, also undated, references Kirk’s identification of the new gentian of 1894 by later authorities:

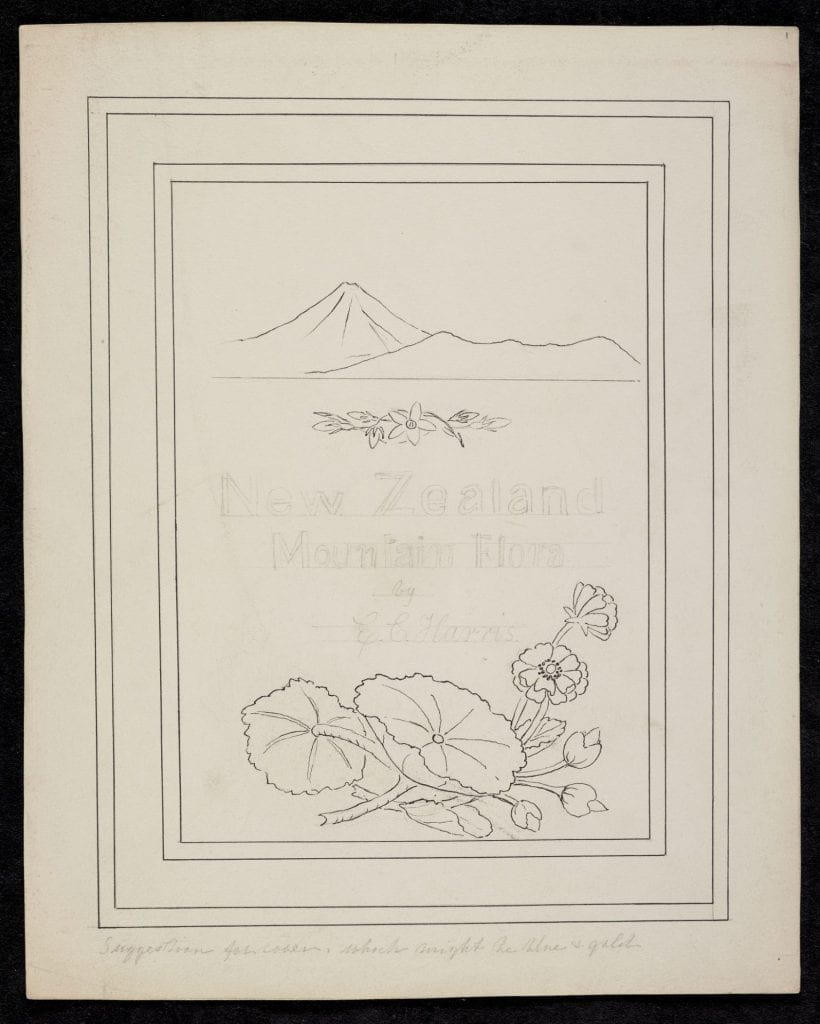

It might be possible to imagine Henry Travers and Emily Harris conferring over one or both plants in Nelson in the early 1890s. But the pieces of the puzzle don’t quite fit and there is no evidence that Travers is the botanical avatar of Emily’s Dun Mountain celmisia or gentian. Nor do the herbariums at Kew or in Auckland offer a match of specimen with painting. What we do have from 1894 is Emily’s cover design for an early iteration of New Zealand Mountain Flora, preserved alongside a later version in the same artist’s book at Turnbull. The 1894 cover features an artist’s palette with Forstera tenella, lobelia and a white gentian that resembles the paintings at NHM and Kew, and the drawing at Puke Ariki:

For the present I’ve put all artistic work aside

There is a later item of correspondence in the Emily Harris collection at the Natural History Museum, the letter she wrote in August 1914 and to which Alfred Barton Rendle, Keeper of Botany at the time, replied in October that year. Rendle’s letter, courteous but non-committal, survives in Harris family papers and as a photocopy at Turnbull. Emily’s letter, on three sheets of onion-skin paper, reprises her earlier dealings with the museum and is the best insight we have for determining the content and nature of her 1894 communication:

34 Nile St East

Nelson August 29th 1914Dear Sir or Madam:

I have been looking forward for months for the visit of the Scientific visitors to New Zealand & now this dreadful war has altered everything.

I am a New Zealand artist & for a great many years have restricted my work to N.Z. subjects, flowers, birds, ferns, berries, grasses etc.

In 1894 I sent three books to the Botanical Department of the British Museum for which I received a letter of thanks, you may have seen them, Flowers Berries & Ferns, I do not remember if they were coloured as numbers were sold uncoloured but later I coloured a great many by hand.

I have been hoping to show you & Dr F. O. Bower the very large collection of original paintings I have in my Studio in oil & water colour large & small paintings finished pictures & panels – also portfolios of rough sketches the work of a long life devoted to making better known the lovely things more difficult to obtain each year.

I am not a botanist but botanists have frequently sent me rare plants if they thought I had not got them.

Many of my paintings have found their way to England & elsewhere. As a child I lived in the bush for some years & so became familiar with the forest trees & flowers & their manner of growth, & have also camped out many times.

Some years ago I made a number of drawings of mountain flora. I wanted to publish it in colours but finding the expense too much decided to sell the paintings & when my relative the late Lord Rendel saw the book he liked it so much that he made me an offer to buy it for his private collection which I accepted. He sent me a message that at any time I wished any one to see the book they would be very glad to show it, so if on your return to London you would care to see a very complete collection of NZ mountain flowers, whoever has it now would be pleased to show it to you.

In conclusion I can only repeat how disappointed I am that I cannot show you so many things I have, too large to go in a book.

For the present I’ve put all artistic work aside and am doing whatever I can to help my dear Motherland.With best wishes

Sincerely yours

Emily C HarrisAddress

Miss E.C. Harris

34 Nile St East

Nelson

New Zealand(Harris, Miss E C (New Zealand). 1914. Natural History Museum Archives, London. DF BOT/400/10/26)

Emily was as good as her word. Family letters from England 1914-15 show that she and other Nelson women sewed and knitted for Belgian refugees in the care of her second cousin Edith Rendel who ran a crèche for mothers and their babies in London. A handful of extant flower paintings dated 1916, still with the New Zealand family, may be remnants of fund-raising for the war effort. There were no further approaches to the British Museum and nothing further was heard of New Zealand Mountain Flora until it surfaced in an estate sale in England and was purchased by the Turnbull Library in 1970. The three bodycolours of 1894 are its precursors, caught in the collections of the Natural History Museum, the sole representation there of original botanical art by women from New Zealand in the period. No Georgina Hetley, no Ellis Rowan, no Sarah Featon. It seems that Emily Harris is singular in her ambition to lodge her botanical art at the British Museum.