Sometimes what was (the past) is a heartbeat away from what is (the present, ourselves standing in a particular location). Worlds coalesce for a moment and then move apart. Here are some highlights from our searches in England that seem to join the dots between one world and another.

- We are in Liskeard, Cornwall, and it is pouring with rain that began as we got off the train and walked into town. Barrel St has vanished from modern maps, the Arts and Heritage Centre at Stuart House is about to close (it’s 4 pm) and we have lost our chance of tracking down the house where Emma Jane Hill taught at a boarding school for young ladies owned by Miss Loveday Adams and her married sister Mary Tickel. The school ran for about 50 years according to Sarah Harris, and it seems likely that Emma Hill, Sarah’s elder sister and Emily’s aunt, was there from the 1830s until her death in 1866. We take photos of buildings in central Liskeard and find out later that Barras St on the old market place is close to where Barrel St would have been. This is about as much footstepping of Emma Hill’s environs as we can manage for one day. Annoyance (we should have checked out 57 Barrel St beforehand) gives way suddenly to remembrance. This is the place where 26 years’ worth of family letters from New Zealand were gathered and preserved by Emma Hill. Here Emily Harris’s early letters (and poems?) were neatly bundled with other family letters. That almost none of the New Zealand letters survived later accidents of history is not important. What matters is the long ago presence right here of those long-distance words. Sarah wrote to Emma about losing herself in the bush between Te Henui and the early settlement of New Plymouth: ’My attention was immediately drawn to the beautiful ferns, Rata trees in flower, the Clematis & others.’ Then later in the same letter: ‘& the field was a garden as Eden of memory.’ Summertime bush, Edenic and lost, overwrites the wet grey streets as we walk back to the station. The letter came here, was read here, would have been answered here.

- Clive Charlton lives in the village of Bere Ferrers on the railway line that runs from Plymouth up the Tamar Valley in Devon. Today the Tamar Valley Line is a spur, scenic and wonderfully redolent of the region’s deep past. The little train, a railcar really, stops at Bere Alston, changes lines and reverses. It descends to cross into Cornwall via the imposing Calstock Viaduct, before climbing again to its terminus at Gunnislake. Back At Bere Ferrers Clive and Nigel Overton show us the memorial to the 10 New Zealand soldiers who were killed here in September 1917 when they jumped out of a troop train to collect rations and were hit by the oncoming London to Plymouth express. School children have made commemorative tiles (a silver fern, three poppies, a kiwi, a sheep, a hei-tiki) and the village still remembers the horror of the accident. Clive explains that the name on the conserved former signalbox, transplanted from Pinhoe, Exeter, in the 1980s is a tad confusing. The owner attached the name by which Bere Ferrers was known when the railway opened in 1890 (Beer Ferris). It’s the vernacular version, the way locals say the name. But the station was soon renamed with the proper version of the village title: Bere Ferrers. The ‘Beer’ was replaced by the more respectable, to late Victorian taste, ‘Bere,’ while ‘Ferrers’ pays respect to the Norman de Ferrers family, who were granted this area after the Conquest (‘When we underwent our comprehensive colonisation episode,’ says Clive). We walk down the steep hill dotted with houses, the estuary of the River Tavy below all mudflats and tidal reaches, a rich mix of pig shit and honeysuckle on the soft air. The old Norman church of the de Ferrers family and its churchyard is filled with stories perfectly legible to Clive and Nigel. We hear some of them before walking back up the hill for lunch at Clive’s house. We won’t get to Dulverton in Somerset where Edwin and Sarah Harris were living in 1839 when they were overtaken by insolvency and its consequences. Dulverton, also small, perches on the edge of Exmoor and is on the river Barl. We may not get there this time but the template of Bere Ferrers offered by Clive and Nigel, layered and intricate with repetitions, shows clearly how Dulverton will also inhabit a long history that only local knowledge can render intelligible to a couple of passing strangers.

- St Andrew’s Church sits as it has always done on Royal Parade in the centre of Plymouth, a mid to late-15th century structure of Plymouth blue sky limestone with Dartmoor granite corner buttressing in the Perpendicular Gothic style. Except that the building we walk into a day or so after looking at Edwin Harris’s painting of the interior in 1825 was reconstructed in the 1950s after taking a direct hit from German bombs in 1941. A headmistress nailed up a wooden sign over a door in the smoking ruins with the single word RESURGAM (‘I shall rise again’), and St Andrew’s did as many churches before and since have done and made itself over from natural or man-made disaster. Today the Resurgam door has the word carved in granite on a plaque that commemorates the restoration. Inside the church is buzzing with activity. It is cleaning day and the local church group is getting ready for an organ recital and choral singing at lunchtime. The underfloor central heating (copper piping set in stone) switched itself on when the cold snap began last week and the docent tells us that the present janitor, ex-army, is fond of telling visitors that St Andrew’s would never have got its magnificent stained glass windows if the Luftwaffe hadn’t provided the city fathers with ammunition for insisting that the old church plans should finally be honoured. And Edwin’s view, looking down the nave from behind the altar rail? We step into the picture, noting differences of detail from what the artist wanted to show in 1825. His roof is not this roof, his chancel is not this chancel. We are standing in a church that has risen from its ashes. A week later we ride across Paris to Gare Montparnasse and see the skeletal remains of the roof of Notre Dame. How long does it take for a ruin to rise again?

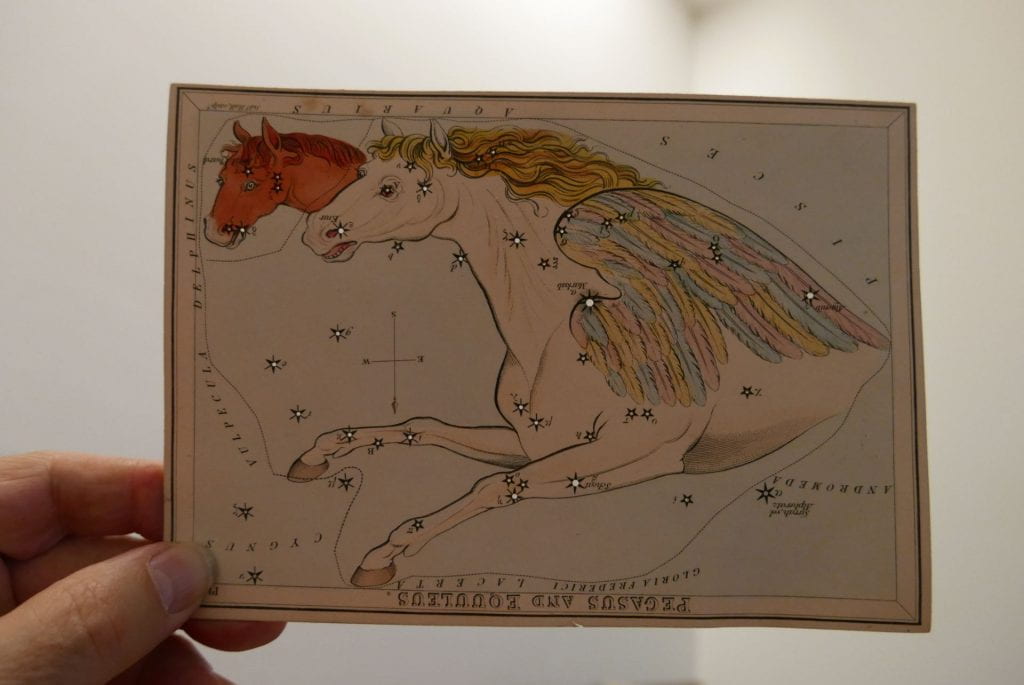

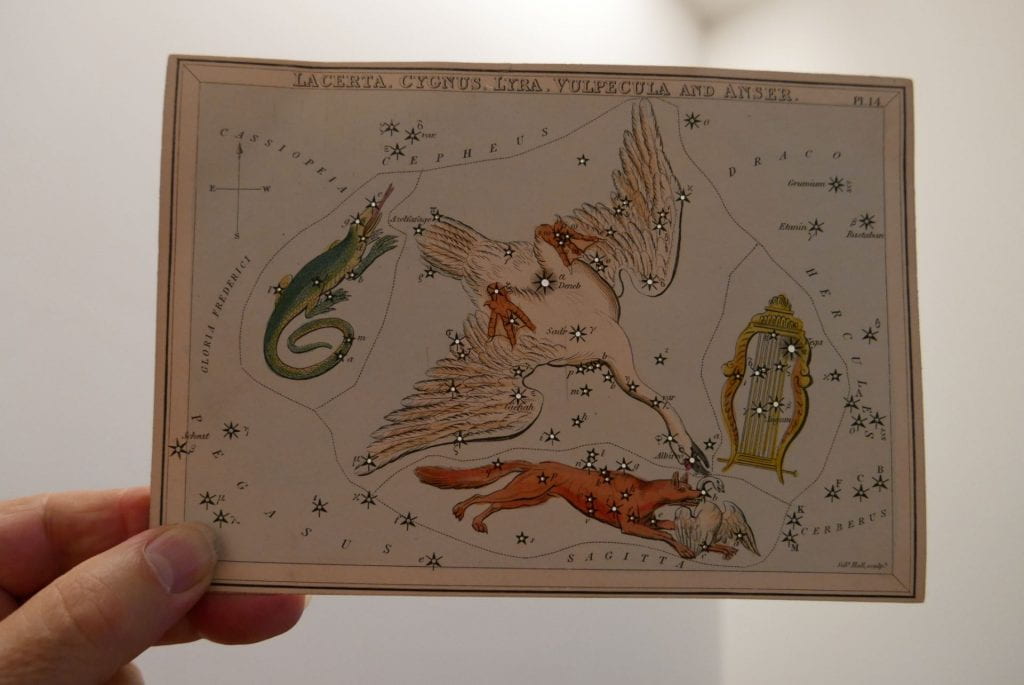

- Urania’s Mirror, or A View of the Heavens is a famous optical amusement first published in 1825 as a set of 32 perforated cards showing the northern constellations. Ostensibly designed by an anonymous lady, the box of cards is now recognised as the work of Reverend Richard Rouse Bloxam, an assistant master at Rugby School. Urania’s Mirror was designed so that viewers could hold up each card in front of a light source and see a painted representation of a constellation with its stars picked out in actual light. Michele’s poetry sequence ‘The Looking Glass’ (2016) takes Urania’s Mirror as a base on which to construct a series of poems named for southern constellations. The sequence was conceived as an edition of alternating black and white pages. The idea was that perforations would throw light (starlight) on the poems as a reader turned the pages. But when Edwin Harris’s optical amusement depicting a view of New Plymouth from Marsland Hill during the war of 1860 showed up with its perforated windows, doors, soldiers’ tents and moon shining on a silver sea, ‘The Looking Glass’ took its place (unperforated and without black pages) as the first component of the collection Vanishing Points (2017) and Edwin’s painting became its cover image. Three weeks ago in London we called up the British Library’s two sets of Urania’s Mirror, curious to see the cards at first hand. One set is uncoloured, the other beguilingly painted in watercolour. Pegasus, winged horse of poetry, has rainbow wings reminiscent of My Little Pony. The Lizard, the Swan, the Lyre and the Fox with the Goose in its jaws reel together in the night sky. We hold up the cards one by one, delighted by their invention. Yes, light comes falling through the perforations, bigger holes for stars of greater magnitude, smaller holes for fainter stars, colour coded to represent their variations in size if not exactly scientific then certainly with charm. Then we noticed the layer of translucent paper pasted to the verso of each card as a precaution against wear and tear and perhaps so that the effect of starlight will appear diffuse rather than twinkling. Such a small detail but one that came flying out of the dark at us because just such a backing sheet mediates the fall of light through the precisely cut holes of Edwin Harris’s view from Marsland Hill. We don’t know where Edwin learned about optical amusements but his painting is linked to Urania’s Mirror by means of an important structural element that strengthens the work physically while enhancing its aesthetic potential.

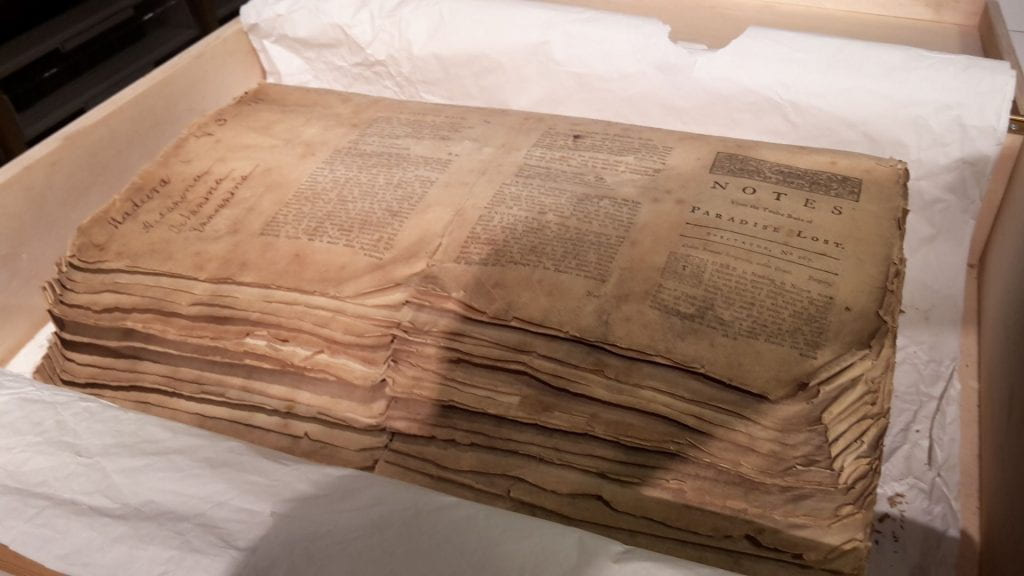

- We are on level 7 of the Darwin Centre at the Natural History Museum in London. Mark Carine, curator of the Algae, Fungi and Plants Division, is showing us one of his favourite items from the collections made by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander as HMS Endeavour set out for the southern hemisphere in 1768. The expedition called at Madeira to take on wine supplies and Banks and Solander got their first chance to botanise in unfamiliar terrain. We are looking at Madeira Bundle 3, its specimens still pressed between sheets of drying paper. Because none of the plants were botanically important, the bundle has remained intact, thus preserving for future eyes part of an 18th century research process. But it is the drying papers that make our day. Before leaving London Banks and Solander visited a printshop and acquired reams of proofsheets to take with them on the three-year voyage to the South Seas. So it is that Notes Upon the Twelve Books of Paradise Lost, Collected from The Spectator, Written by Mr Addison, travelled to Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia and Batavia, enfolding Banks and Solander’s ever-growing collection of plants dried with the aid of Joseph Addison’s absorbing and absorbent text.

Lead writer: Michele Leggott

Research support: Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis