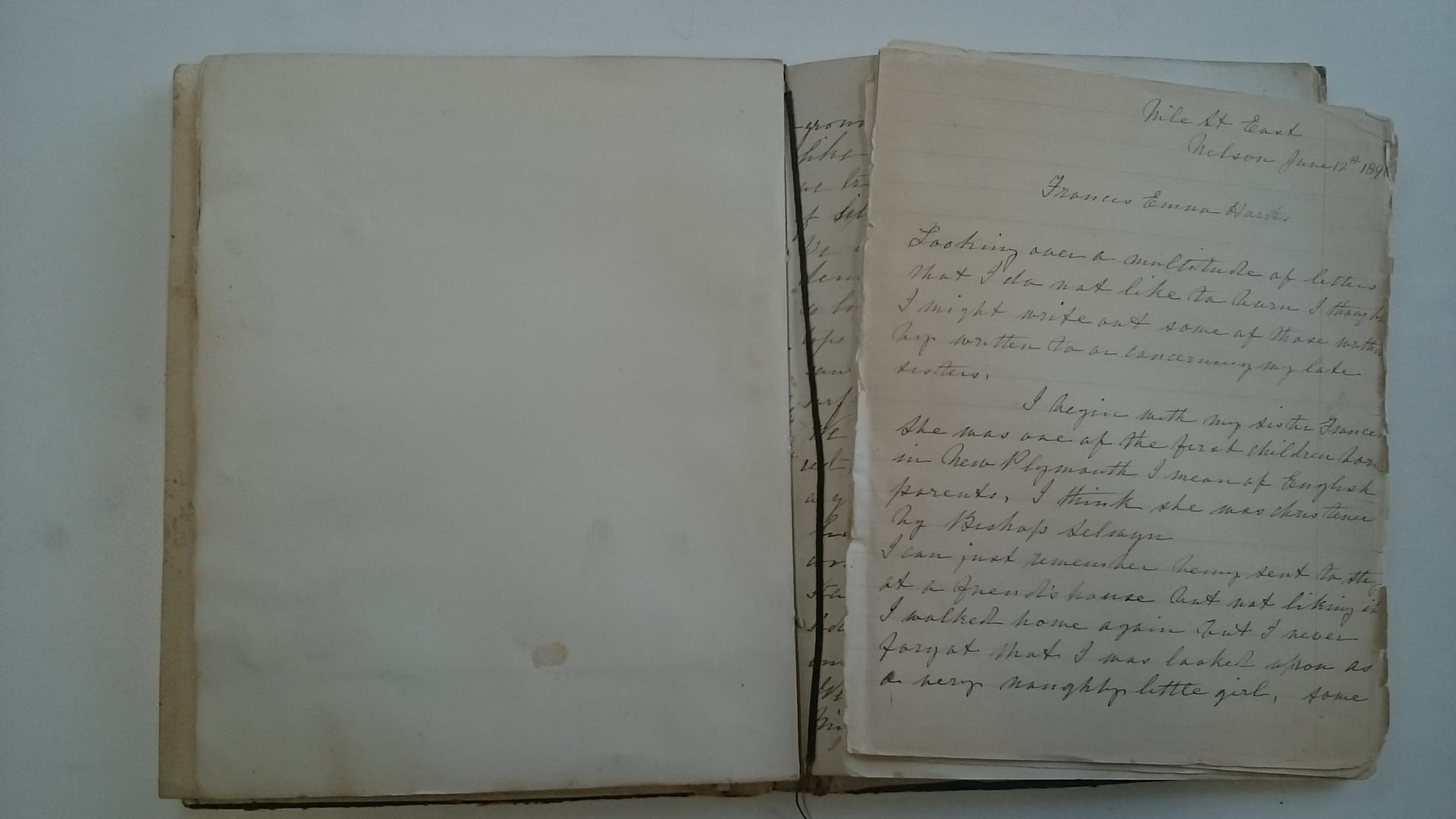

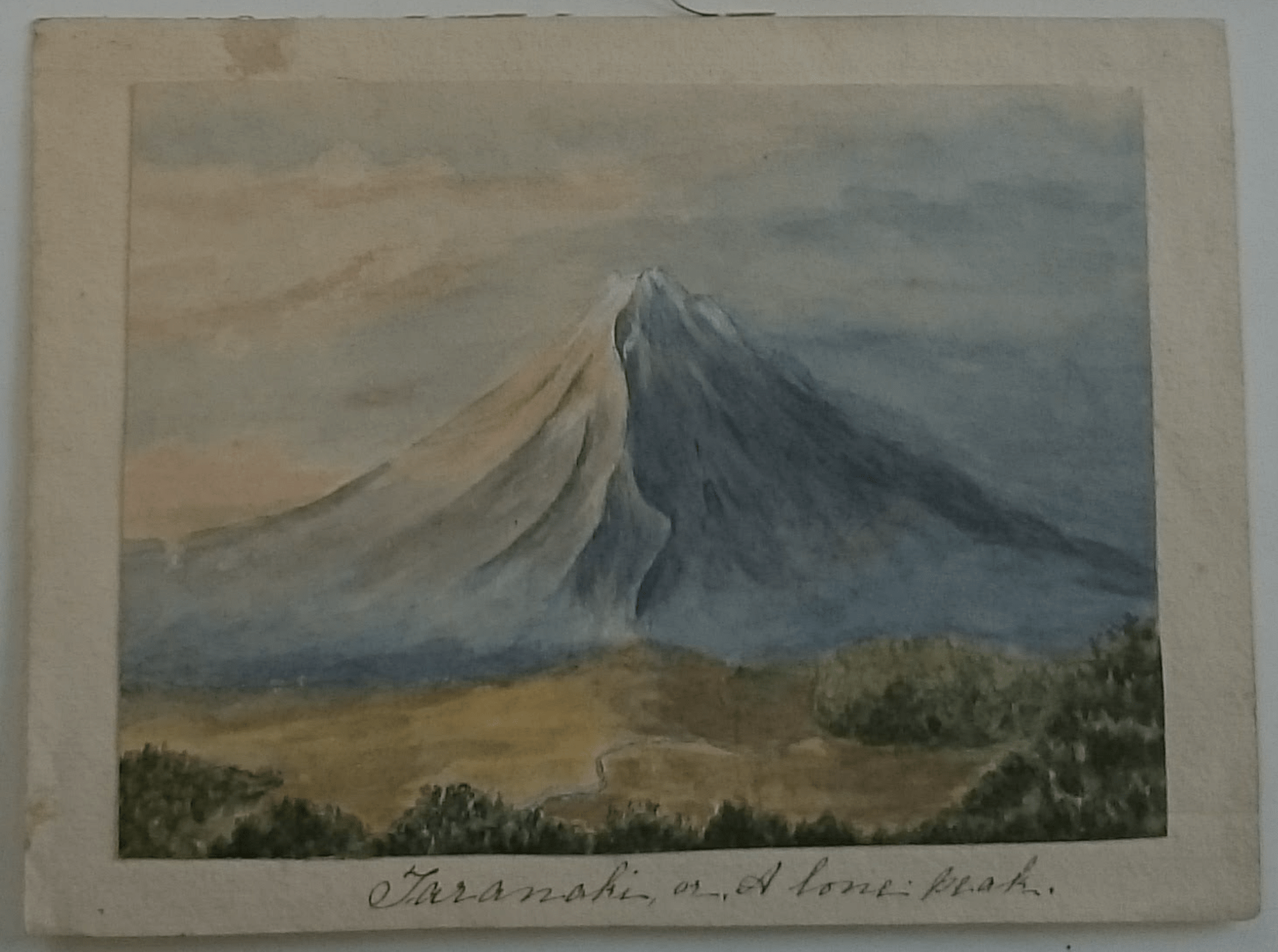

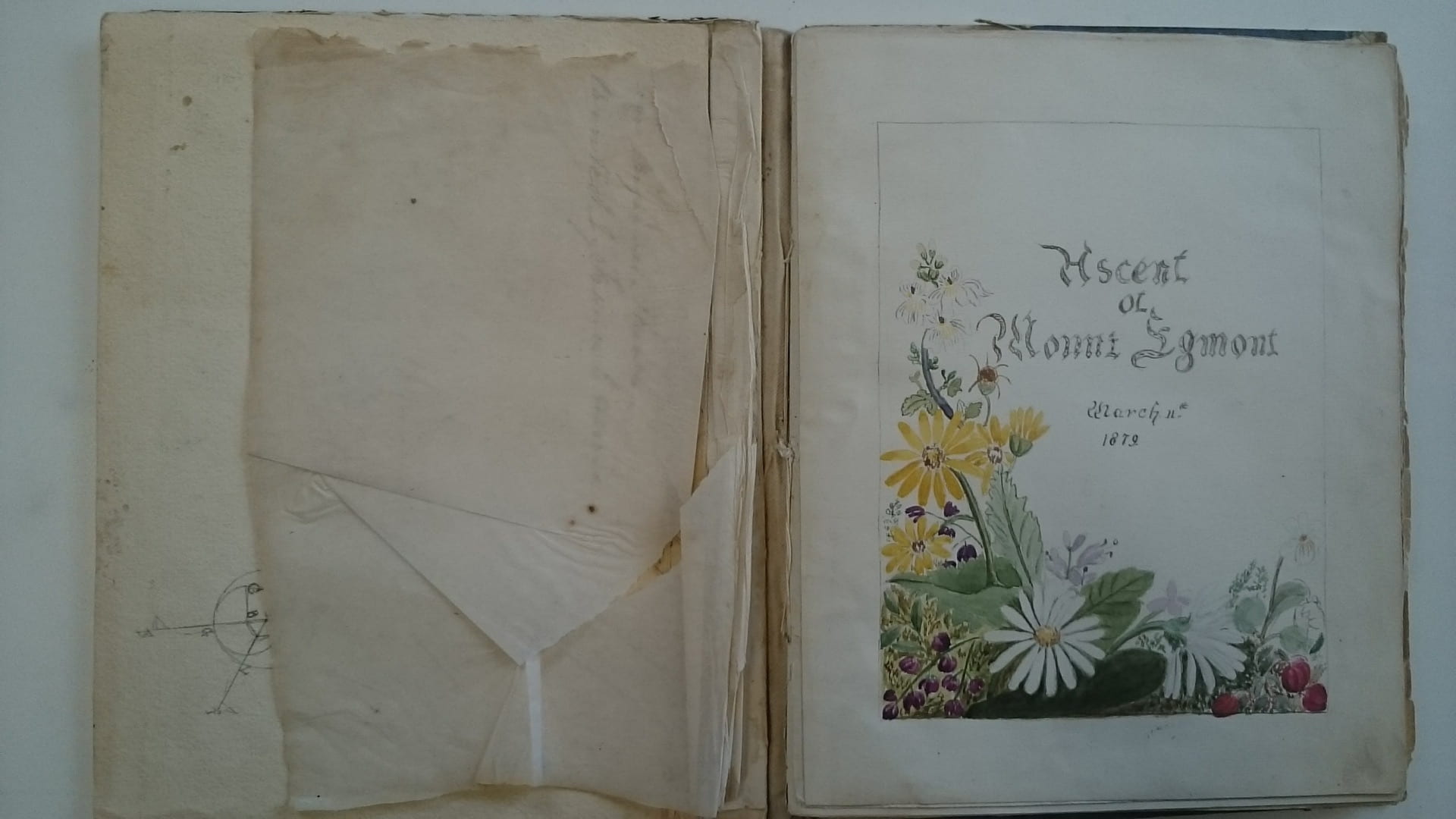

Frances Emma Harris. ‘Ascent of Mount Egmont. March 11th 1879.’ MS journal interleaved with 10 watercolour and ink sketches. And ‘Notes on Frances Harris’ by Emily Harris, Nelson, 12 June 1898, loose pages found in journal. Briant Papers.

Ascent of Mount Egmont.

March 11th 1879

On the morning of March the 11th I arose shortly after 5, finished my preparations for our expedition to the mountain and after taking a cup of cocoa was ready to start by 6.30.

My travelling costume consisted of a short dress of grey homespun, black jacket; a hat; strong leather boots, riding gloves et cet; my swag contained a rug, and a few necessaries for ‘camping out,’ I had a small basket for ferns, wild flowers et cet, which I could strap on my back, that being the easiest mode of carrying it.

Our party consisted of three ladies and three gentlemen and a guide. One lady was under the impression that we were only going to the ‘ranges’ and thought that we meant to return that night. On being assured that we had plenty of blankets she exclaimed: ‘at least I might have brought a tooth brush.’ She was offered the loan of one, which caused no little amusement.

Our intention was to [be] absent four days, to ascend Mount Egmont on the second day, and visit Bell’s falls on the third, and return to town on the fourth. We started at 7.15 in an express, with a pair of strong horses, carrying with us tents and provisions. The morning was lovely! We drove eleven miles inland along a rough but picturesque country road. We passed on the way a second party of nine men and boys under the leadership of Sergeant Brooking, also bound for the mountain.

When we reached Coad’s we were joined by Mr J.B., and the guide Stephen Coad. We were stopped by a fallen tree from driving further so we all got out and had breakfast. The express then turned back to town. The guide packed the tents and started for the camping ground in order that the tents might be put up before the dew, which falls early among the mountains, had wetted the ground. Whilst breakfasting Mr B.R., a gentlemen belonging to a third party, found us. Mr S asked him to join us, but he declined, saying he had already breakfasted four times and could not manage a fifth.

After breakfast we ladies walked on leisurely, leaving the gentlemen to make up their packs. Our road lay through a farm that had been abandoned during the war. Dead trees were covered with rata creeper in full flower, whilst ferns and native shrubs were growing wherever there was the least shelter. The house had been burnt by the maories, but fuchsia and blackberries still mark the spot where the garden had been. The gentlemen soon joined us heavily laden, I did pity them.

We had now entered the track through the bush and were in fact ascending the ranges, which are, I believe, between 3 & 4,000 feet above the sea level. The track is cut through dense forest and winds about; you cannot see very far ahead. It is impossible to judge of distance or height, for all around these is nothing but trees which meet overhead. There is no climbing to be done yet, excepting here and there we had to take a good step up. It was very muddy in places and we were very glad of some long poles which I found on the way.

Although suffering from headache, I was not so tired as on my first ascent of the ranges last month. My companion Miss F was however very tired so we rested by the side of a tiny stream and ate some apples which were pronounced by the gentlemen (who soon joined us) to be excellent.

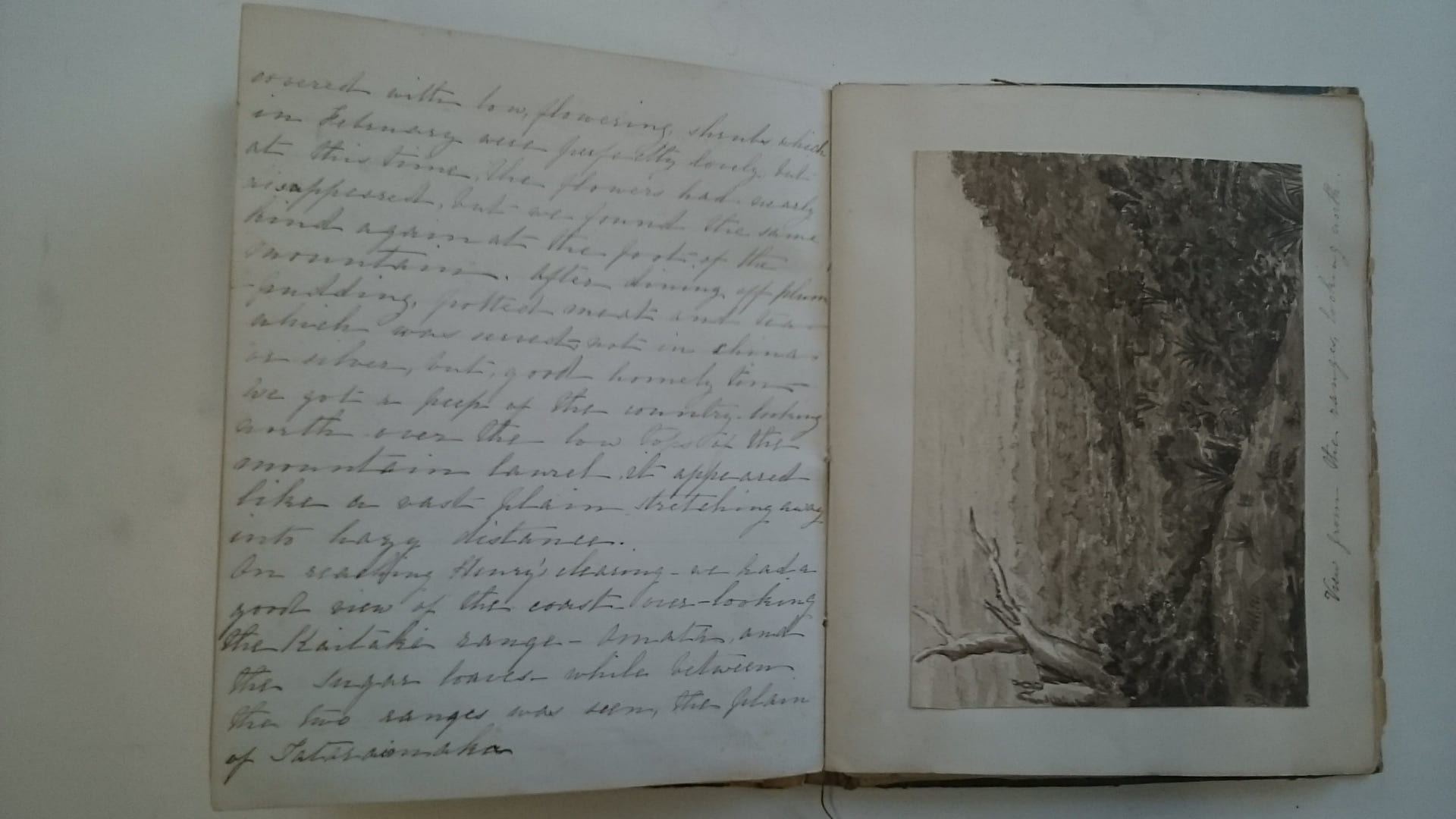

On reaching the top of the ranges I noticed that the trees were much more stunted and different to any that I had seen before, whilst quite at the top is either bare or covered with low flowering shrubs which in February were perfectly lovely but at this time, the flowers had nearly disappeared. But we found the same kind again at the foot of the mountain. After dining off plum pudding, salted meat and tea which was served not in china or silver but good homely tin, we got a peep of the country, looking north over the low tops of the mountain laurel. It appeared like a vast plain stretching away into hazy distance.

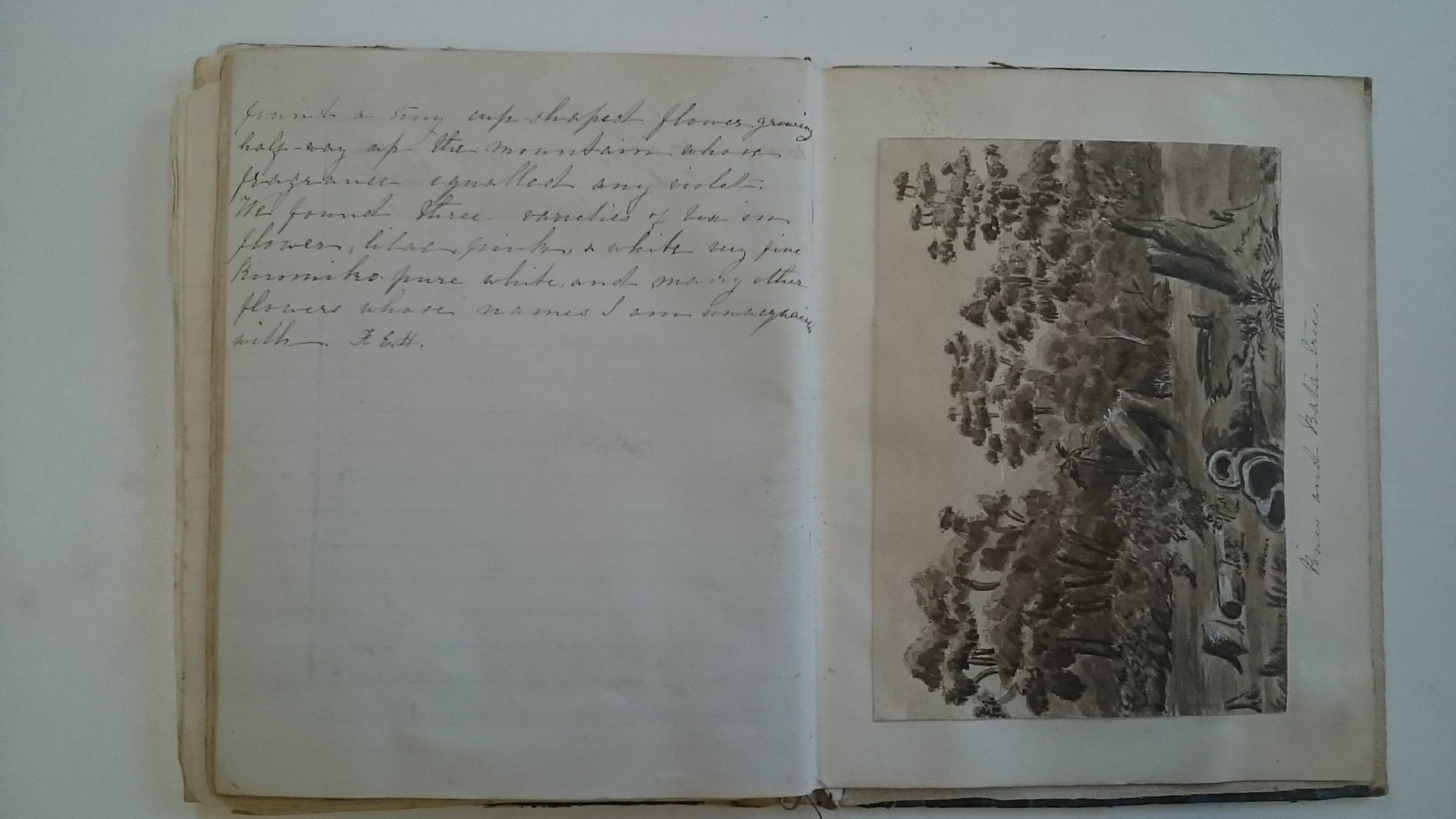

On reaching Henry’s clearing we had a good view of the coast overlooking the Kaitaki range — Omata and the Sugar Loaves — while between the two ranges was seen the plain of Tataraimaka.

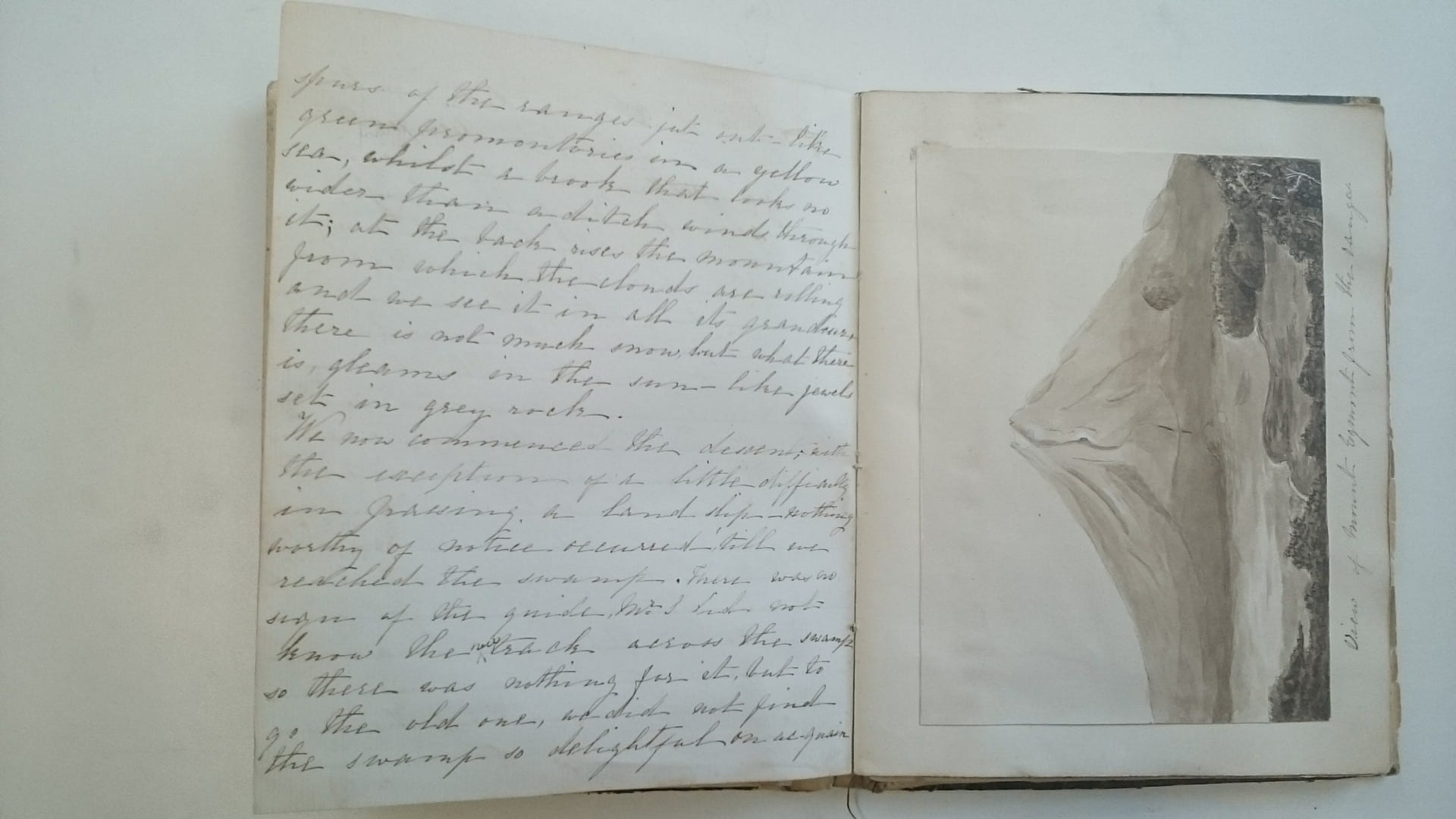

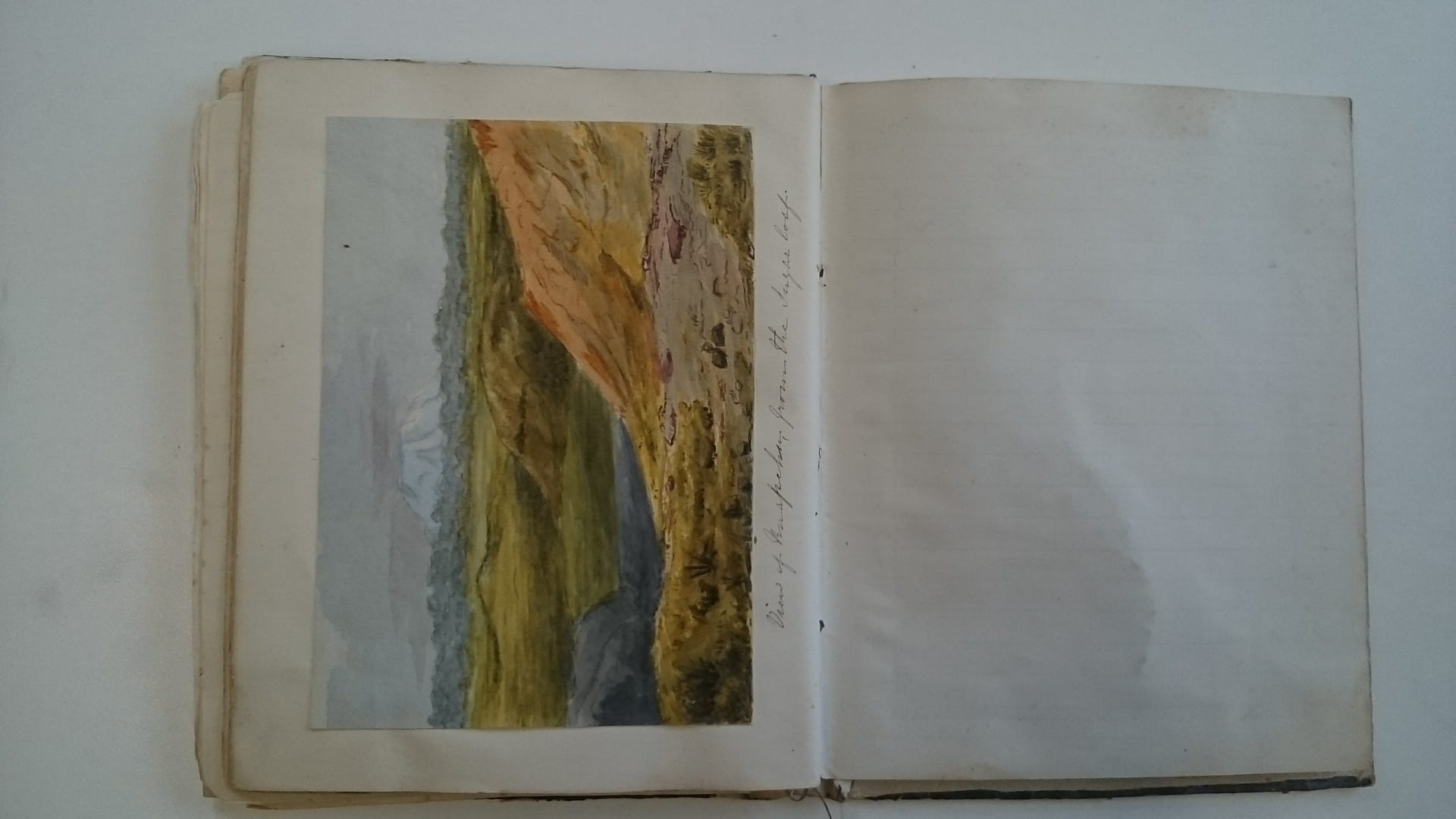

We had still some distance to go before reaching the top. The path was a side cutting around one of the highest peaks of the ranges, winding in & out then taking on a sudden dip down & up again out to another part of the range whose flat top is covered with grass, daisies &c and strewn with little stones covered with perfectly black moss that made one think the kitchen chimney had taken fire and covered the place with soot. From this point you get a splendid view of Mount Egmont as it rises from the swamp. Imagine yourself standing on one of the rounded tops of the ranges: at your feet the swamp forms into a half circle round the base of the mountain and numerous spurs of the ranges jut out like green promontories in a yellow sea, whilst a brook that looks no wider than a ditch winds through it. At the back rises the mountain from which the clouds are rolling and we see it in all its grandiose. There is not much snow, but what there is gleams in the sun like jewels set in grey rock.

We now commenced the descent. With the exception of a little difficulty in passing a land slip, nothing worthy of notice occurred – ‘till we reached the swamp. There was no sign of the guide, Mr S did not know the new track across the swamp so there was nothing for it but to go the old one. We did not find the swamp as delightful on acquaintance as it looked from a distance.

It is composed of moss piled layer on layer into which you sink knee deep if you make a false step, and then there is nothing for it but to sit down on a tuft of grass and pull out one or both feet as the case may be. We had not gone far when we came to a river which we crossed safely on stepping stones. Mr S hurried on to find the way, and I after him; to stop was fatal. Imagine the fatigue of pounding away at such a rate, my head throbbed painfully. I saw our leader’s white puggaree disappear suddenly, where I knew not. I had gone rather too far and into some dead scrub, so had to retrace my way back to the rest of the party who had found a rock to rest on. Mr S. reappeared as suddenly as he had disappeared; he said he had found the way down to the river. We were helped down a steep bank to the river-bed. Miss M, going first, slipped and sat gracefully down in the water. When we were all safely down, Mr S and Miss M had flown we had no idea where.

After some search Mr B found their wet trail along the rocks, helping me over the worst places. I followed his lead, springing from stone to stone with an agility that surprised myself. But the sun warned us that it would soon be dark. Feeling that my strength would not hold out much longer, I was greatly cheered at hearing voices approaching. It was the guide and one of the gentlemen from the 2nd party. The guide told us that we had come the wrong way, that he had arrived at the camping ground at 3 o’clock and put up the tents. He then came to meet us, to take us over the swamp, but not hearing or seeing anything of us he concluded that we had turned back, so returned to the tents. Mr J.B. & the guide went back for Mr S’s swag which he had left on a stone in the river. I went on with Mr B.R. who cautioned me to be careful, as there were holes. Catching sight of Miss M drying herself at the fire, I forgot the warning & fell flat into a hole, fortunately a dry one. It was quite dark. Thanks to the courtesy of Sergeant Brooking immediately on arriving, he sent us over hot tea which we greatly needed. When we had all assembled round the fire we had tea & were very lively; stories were told & songs sung. The bread and biscuits had to be dried, they had fallen into the river. Everything we touched was dripping with dew and it was so cold we were glad to wrap ourselves in anything warm we could get hold of. I had a gentleman’s coat on.

I shall never forget the scene as we sat round the fire on tufts of grass. On either side were the tents, before us “Egmont” looking hugely grand but cold and grey. Over a spur the moon was rising, making the shadows more intense. The Southern Cross looked bright and friendly. On our right were thick wooded hills, in the distance we heard the roar of Bell’s Falls broken by the hooting of an owl.

Our neighbours on the other side of the camping ground seemed very merry, but presently all was still, save the barking of a little dog. At 9-30 we retired to our tents and had our first experience of camping out. Owing to our being too late in arriving, nothing had been done to make the tents comfortable. The ground was covered with branches of cutting grass on which it was impossible to sleep. The rats ran over us giving us great fright.

The next morning was everything we could desire. After an excellent breakfast of cocoa and mutton steak toasted on long sticks, we made ready for the mountain. We started at 6.30. Passing through scrub we came to a steep cliff. In going down I was so unfortunate as to start a big stone which rolled against the guide’s legs. Greatly to my relief he was not injured in any way. At this point the other parties passed us, swarming over the cliff like monkeys, setting the stones rolling right and left.

We next came to a stream with steep wooded banks. Brooking’s party took the track west to the stream, but our guide thought we should get wet if we attempted to cross the stream which we must do several times. So we chose a track higher up the bank which we found sufficiently exciting, emerging into a rocky valley down which a stream rushed noisily until it joined ours. In fact it seemed ‘A land of streams!’ ‘Some like a downward smoke, slow dropping veils of thinnest lawn did go; and some thro’ wavering lights and shadows broke, rolling a slumberous sheet of foam below.’

Following the stream to its source [we] crossed it twelve times, then passing over huge boulders we came to the drop, so named from the fact that on returning we had to hold on to the branch of a mountain laurel and drop down several feet. The drop not looking very easy of access, the guide went up a hill we called, the castle to see if that was easier. Thinking so, he called to us to come on. We left Miss F with Mr J.B. who had stopped behind to get water; we four went on. When we got to the top of the castle we could see nothing of the guide, in fact there was nothing to see but laurels growing so thickly together it seemed impossible to get through. Mr S said we must go back, but finding us determined to push on he went down on hands and knees and crawled under the laurels; we followed in the same fashion. The mountain laurel is a shrub with variegated leaf and white stem, very hard to break or bend. We found we had not to go far on all fours. The shrubs getting farther apart, we went on. Some were almost buried in deep moss of a whitey green colour, which felt so soft and springy. We flung ourselves down on what seemed to us the most luxuriant of couches, to rest and wait for the guide who soon made his appearance carrying the billie with water & Miss F’s red shawl. He brought word that Miss F had succumbed to the difficulties of the way after having accomplished the drop. Mr J.B. had to stay with her & at 4 p.m. they found their way back to the camp. Mr J.B. with his usual good nature smoothed the ground in our tent and cut flax and grass for our bed, which on our return we greatly valued.

We might now be said to have fairly commenced the ascent of the mountain. There was no more climbing up steep cliffs but a steady ascent, very gradual but, oh! so long. For some distance we walked on the moss which felt like Turkey carpet, but even Turkey carpets on an inclined plain are trying to walk on and we got tired of the moss.

We next came to the rock and had to use the greatest care in our movements not to disturb the stones, which if once set rolling by those in front proved anything but pleasant to those behind. Even large boulders frequently looked so unsafe that we thought it best to avoid them by going round. Usually this part is covered with snow and the traveller goes through the scoria a little to our right. On our left was a high wall of rock which from New Plymouth looked like a large hump on one side of the mountain. Mr S gave us small doses of brandy & we ate a little potted meat, which stimulated one to fresh exertions. Poor Miss M showed symptoms of knocking up, her breathing becoming more and more difficult the higher she got.

The view was magnificent. The ranges formed a lovely group: over the tops we saw the blue line of sea, the Sugar Loaves at the foot of Sinclair’s [St Clair’s] table and other lovely low hills thickly wooded. As a foreground the treacherous swamp, looking like a harvest-field.

Looking south we traced Stoney River, like a thread of silver hurrying on to the sea.

We could not see Nelson owing to the dense masses of clouds which hung so low that they seemed to rest on the tops of the forest trees. Here & there we saw the coast-line with the white surf breaking on the beach.

We resumed our climbing after a short rest. Mr S pointed out the spot where a young lady eight years before had been obliged to give in, having completely worn out her boots. She staid for two hours on the mountain side and the clouds came up and enveloped her.

We were now in advance of Mr S and Miss M. The guide gave it as his opinion that the young lady would never reach the top, and that if we did not press forward we should not have time to get there. He also told us that many men had given up before reaching so far. I was frightfully tired but did not mean to give in. My short stick was a great help, either to walk with alone or to hold on to one end while Mr G held the other. It helped to keep one steady. On looking we could not see anything of Mr S & Miss M so concluded that they had given in. We heard a loud report like a cannon. Looking at the top of the mountain we could see a slight cloud of dust and then a tremendous stone came thundering down, causing us to hold our breath as we silently watched its course till it had passed those below. We met a man & boy returning; they seemed disappointed at not being able to reach the snowfield. Not to see the crater is like dying within sight of Jerusalem. The rest of the party now came in sight; they [had] reached the top of the mountain at 12.30. They offered us snow-water to drink; we asked them to give some to those below us’. On Mr B.R raising his cap and wishing me farewell, one of the men suggested three cheers for the lady. Mr G said he thought I began to flag after that, but I think I did better.

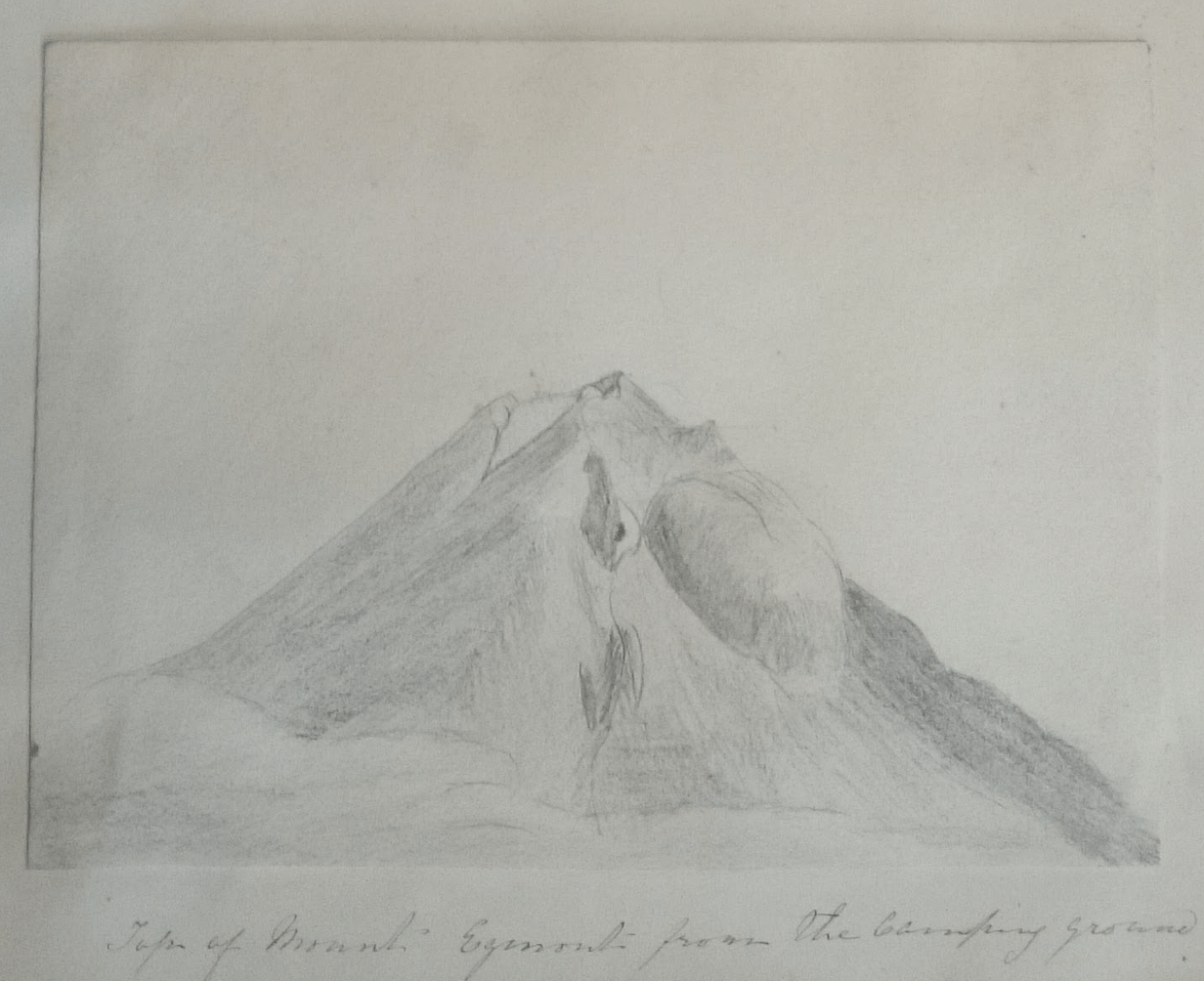

At two o’clock we reached the hump; here Miss B stopped on a former occasion. I must confess that I had a much greater respect for her having reached so far than I had at starting when it appeared such a short way from the top. With the least persuasion I should have staid there myself and considered that I had done wonders. We rested a short time and enjoyed the view of the town and roadstead: at our feet the forest and open country stretching for miles and miles away north and south. A little to the right we could make out Inglewood. I think that I must have risen several degrees in the estimation of the guide, who evidently had a poor opinion of women as mountaineers, when he said that as I had got so far I must go to the top. I said ‘yes, if you will help me?’ We had now the most difficult part to ascend. Passing between the hump and the mountain we came round to the town side. After climbing a little way the most lovely view broke on our sight: standing out clear and sharp against the sky were Ruapehu and Tongariro. I shall never forget the scene, to describe it were impossible. It may not be out of place here to mention that two gentlemen made the first ascent of Ruapehu about this time.

Then upward, onward, over loose scoria. It was a case of three steps forward and two back. I held on tightly to two sticks which were held one by the guide, the other by Mr G; in this way we reached the top. Coad said, ‘we will just go up, turn round and come down again.’ But I begged for a quarter of an hour to rest and sank down tired out within a few yards of the first snow I had ever been close to. I contented myself with looking down upon it and marvelled that that which looked like a tiny speck from below should cover so large a space.

We dined off biscuit and a little potted meat. We had a wonderful panorama stretched out before us: from the White Cliffs to Stoney River and right away over the clouds to ‘The Other side of nowhere’ and then again inland over a sea of forest, with the blue smoke of Stratford hanging like a faint mist over the settlement.

I cannot describe the top of the mountain for the best of reasons: I did not see the whole of it. We were higher than the field of snow where the crater is, which by the way is filled with stones and snow. The side we ascended brought us into a small space at the side of the pinnacles which were connected by a rocky wall almost perpendicular. Boys and men have been known to get over or round it but not often. There is another way of ascending Mount Egmont from the German settlement but for various reasons it was not considered so [good] as the way we chose.

When we got back to the hump, to our delight we found our friends had arrived there. The mountain air had had the same unpleasant [effect] as a trip by sea on Miss M who was quite done up. With the help of ice on our own way down, she recovered wonderfully. I think she displayed great courage in persevering as she did. At 3.15 we continued the descent. Coming down through the scoria we had to be careful not to send too much down. The better to preserve our equilibrium we came down hand in hand, over our boot tops in scoria with a few yards of it moving all around and now and then a stone flying overhead. When we reached the moss there was a general emptying of boots which were filled with little stones. I may remark here that going up the mountain we wore out the toes & coming down the heels of our boots. I noticed that the guide had his protected with copper plate.

Our adventures going back would take too long to tell. I remarked that the gentlemen looked rather grave if we loitered at all, and there was a decided inclination to push on. I did not apprehend any difficulty in getting back although I was aware we had left the mountain an hour later than we should have done. When the bush was reached it was dark and Coad thought that instead of scrambling along the bank as we had done in the morning, we should keep to the stream. The dense growth on either side made it so dark that it was impossible to see a yard in front of us. Sometimes I could see a hand stretched out to help me. Fortunately we could hear each other speak but the injunctions to ‘step here where my foot is’ and, ‘don’t get your feet wet’ were quite thrown away. So there was nothing for it but to go boldly and not to mind if one had to stand for five minutes in the water whilst the guide struck matches to make sure of the way. As he had not been there in the dark before, great praise is due to him for bringing us through safely. After successfully mounting the cliff with the loose stones we got into the scrub close to the camp, when the guide said he had lost the track and a great many matches were struck to find it. We heard the cooeying from the camp in answer to ours, it seemed quite near. At last the track was found and we rejoiced to hear the cheerful voice of Mr B as he came to meet us. He had lighted a fire in the track to guide us but we could not see it until quite close. Our tent looked quite comfortable. We did not stay up late that night nor were we quite so lively; fourteen hours travelling had taken it out of us.

We slept soundly in spite of rats which we knew visited us. They seemed to have a fondness for leather straps as well as boots which they carried outside the tent. On waking the next morning we thought it was raining heavily but it was not so. The wind had risen and was flapping the side of the tent against some rushes and, the dew being very heavy, sent a shiver of drops in our faces. Indeed everything that was not under the blankets was decidedly damp. After making an elaborate toilet dipping our towels in some muddy water in a [pool?] we were ready for breakfast.

Our captain, thinking the weather was about to change, decided that we had better return as far as Mr J.B.’s. The way back over the swamp was much easier, the guide taking us a much shorter way and avoiding the river. We were a very merry party, Miss F taking the lead, and the mountain echoed back the Tyrolean call which she gave from time to time.

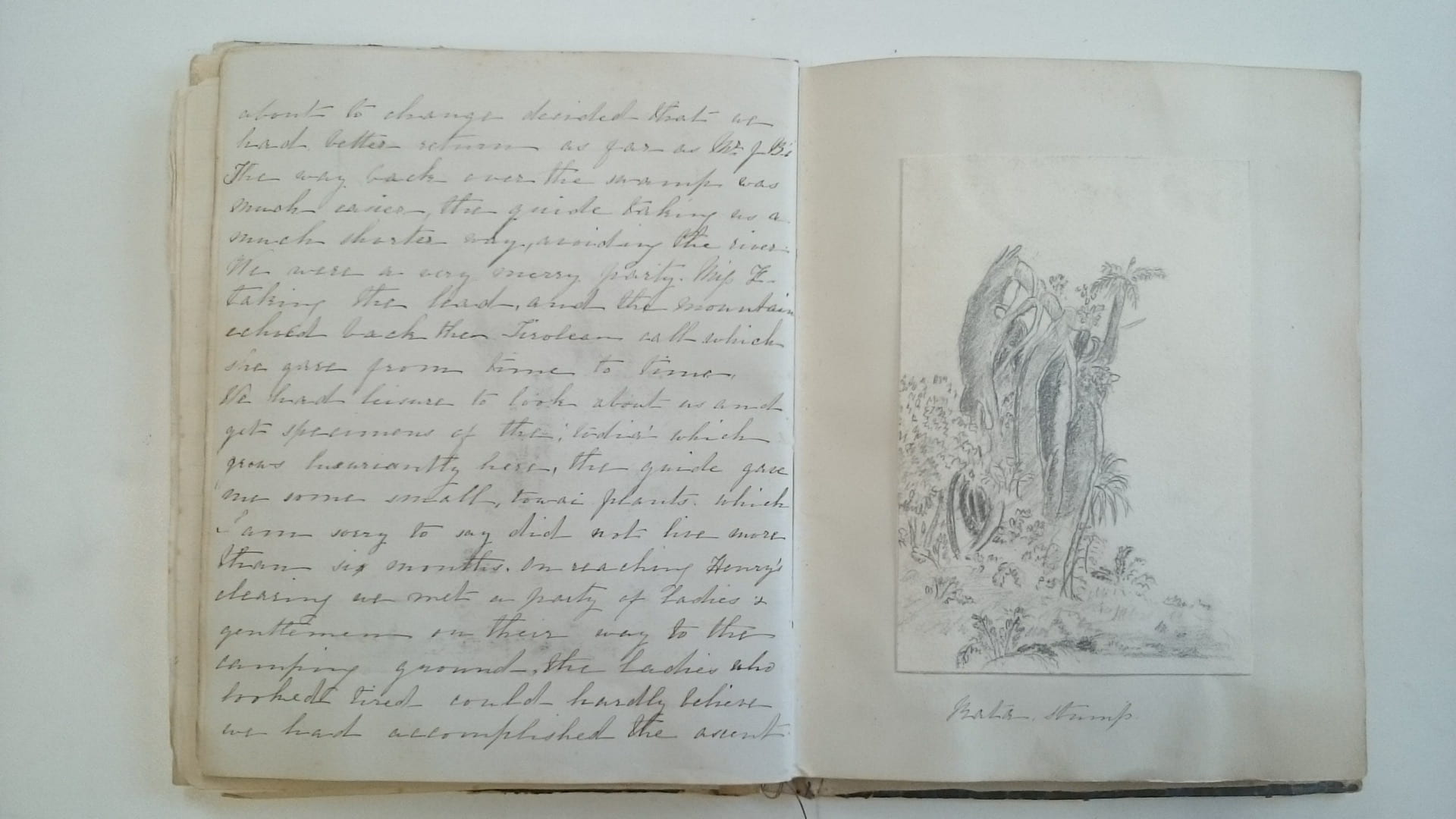

We had leisure to look about us and get specimens of the ‘inaka’ which grows luxuriantly here. The guide gave me some small towai plants which I am sorry to say did not live more than six months. On reaching Henry’s clearing we met a party of Ladies who looked tired and could hardly believe we had accomplished the ascent

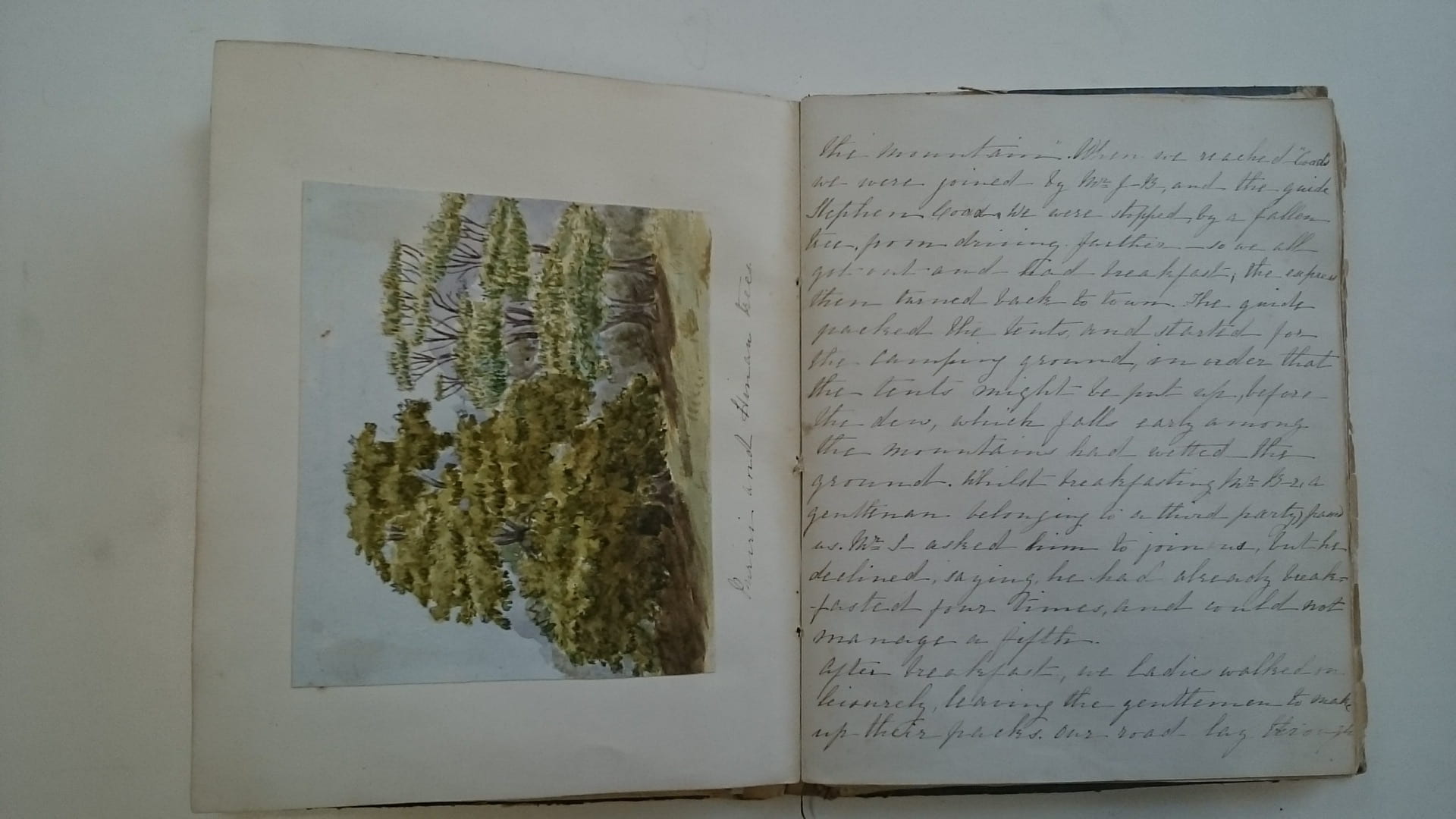

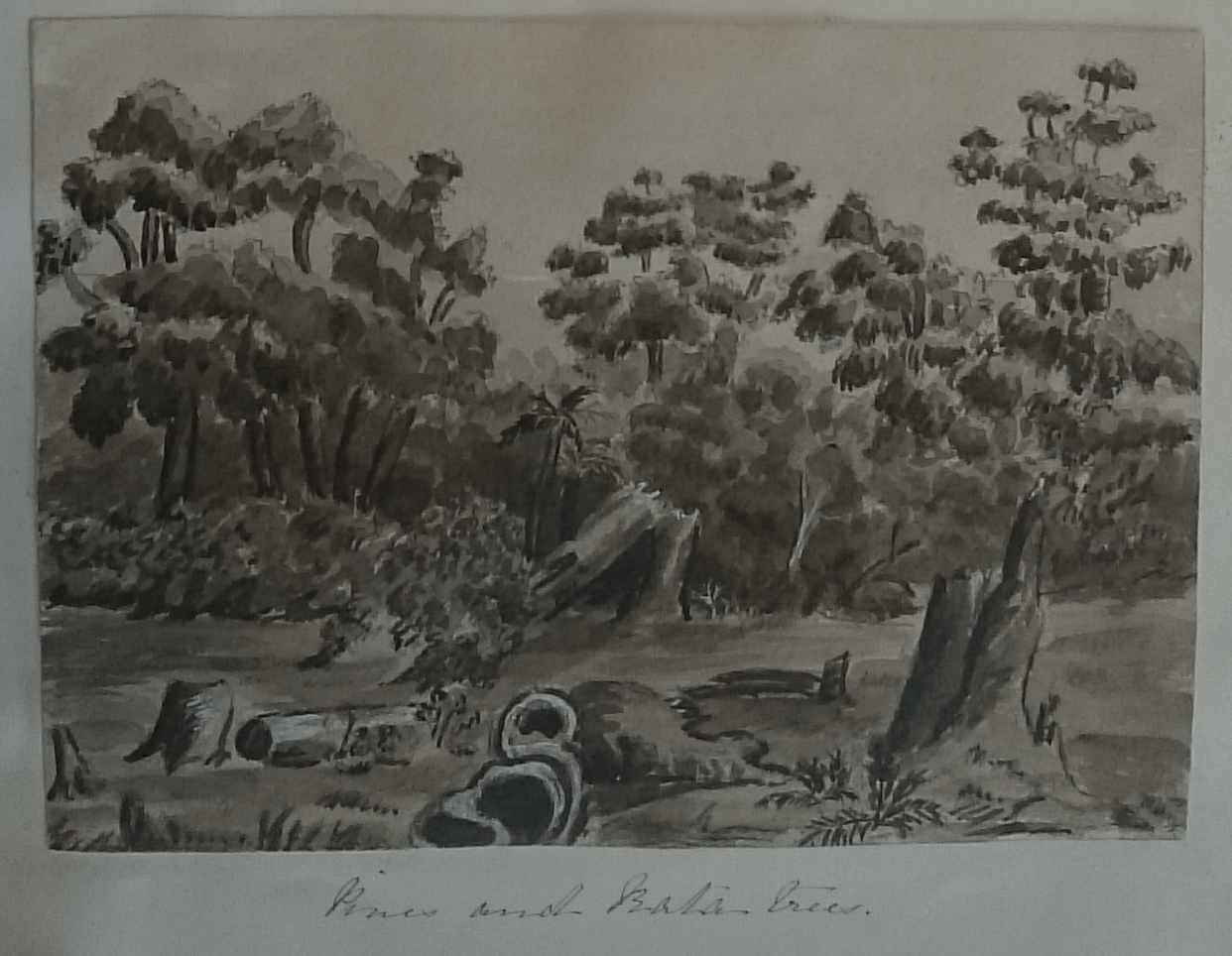

We dined at the old camping ground and Miss M sketched the party in various attitudes whilst the dinner was being prepared. As we had returned to the open country a day sooner than we intended, there was no express to take us to town so we accepted the very pressing invitation of one of our party to stay at his house till the following day. One of the ladies being very anxious to return to town that night, Sergeant B kindly offered her a seat in his dogcart. We reached Coad’s at 3.30. While Mr S saw about a comfortable seat for our companion, we went on a little way and stood on a stump. As she drove past us we sang the call which she answered, then the men gave three cheers and drove off. We spent a very pleasant evening appreciating the comforts of civilisation. The next morning our host showed us the beauties of his farm. After visiting the shell of a rata tree which would hold fifty sheep, the gentlemen went to look at the wild cattle whose bellowing we could hear incessantly. We settled ourselves to sketch the magnificent group of pines and rata trees.

About eleven am the express arrived with Mrs S and Miss F with fresh provisions, expecting to find us half starved at the foot of the ranges. We arrived in town at 5 pm, rather tired but in excellent spirits after a most delightful expedition, the difficulties of which only added to its interest; and I recall with pleasure the quarter of an hour spent 8400 feet above the level of the sea when I looked on my native land from amidst the perpetual snow of Mount Egmont.

Frances Emma Harris.

The ‘Flora’ of the mountain is very beautiful. Cedar trees cover the ranges with their dark green foliage [which] is mingled with the bright red and purple of the Pepper plant, whilst in the more open parts tiny florets gladden the eye at every turn. Amongst the most common are the Primula and several varieties of daisy. Modest white violets bloom but unlike their English cousins, no perfume is ‘wasted on the desert air.’ To make up for that want we found a tiny cup-shaped flower growing halfway up the mountain whose fragrance equalled any violet. We found three varieties of bush in flower, lilac, pink & white; very fine Koromiko pure white, and many other flowers whose names I am unacquainted with. F.E.H.

Emily Cumming Harris, Notes on Frances Emma Harris. Nelson, 12 June 1898

MS notes on Frances Emma Harris. Written at 34 Nile St, Nelson, NZ, 12 June 1898. Found in Frances Harris, ‘Ascent of Mount Egmont. March 11th 1879.’ MS journal interleaved with 10 watercolour and ink sketches. Briant Papers.

Looking over a multitude of letters that I do not like to burn I thought I might write out some of those written by, written to or concerning my late sisters.

I begin with my sister Frances. She was one of the first children born in New Plymouth, I mean of English parents. I think she was christened by Bishop Selwyn. I can just remember being sent to stay at a friend’s house but not liking it I walked home again but I never forgot that I was looked upon as a very naughty little girl. Someone however told me that I had a new little sister. The next I remember we were living at the Henui, baby was two years old and had not been weaned & the difficulty was how to manage, she used to scream so.

When she was a few years old we were all playing near a stream in the garden and close to a well a few feet deep. We were playing houses, little France’s seat was pushed back & back until suddenly she fell head first into the well. Our loud cries brought my mother and she stooped down & catching hold of her feet pulled her out dripping wet and nearly drowned. She was a fine healthy child & it did her no harm. Some time after we were playing near the gate, some ladies stopped to speak to us. Afterwards they told some friends that little Frances Harris was the most beautiful child they had ever seen. No doubt it was true but I cannot remember her then. She had plenty of dark hair, grey eyes & very regular features. Later on Mr Donald McLean (afterwards Sir Donald) came to live near us. He & my father were great friends at that time. He was very tall & big. He greatly admired the little girl & used to hoist her up on his broad shoulder, carry her off to his house & regale her with bread & butter and sugar. Sometimes he would send his man for her. She seemed to like going. But another time when some friends (the Nairns) wanted to keep the two little girls Kate & Frances they could do nothing with her and had to bring her home. Kate was all smiles & quite happy with them.

One day I went for a walk with my brother & Frances. We went as far as the Wawakio [Waiwhakaiho] river to see the beautiful suspension bridge that had broken down in the middle. Father made a sketch of the bridge, before it broke down, a lovely river then with trees and shrubs on both sides. When the bridge broke down a canoe or boat was kept for people to row themselves over. Corbyn rowed himself half across the river & finding it very delightful offered to take us & we were only too willing to go. He managed to row to about the middle of the river then could not get farther, do what he would. The current was too strong & the canoe began drifting down the river. Then two men came on the opposite side & wanted to cross & kept calling out directions but nothing could be done. We kept drifting until we got nearly under the bridge then one of the men, a young Maori, climbed along the broken chain & just as we were under dropped into the canoe. He quickly rowed us across & we went home very much frightened at our narrow escape. How many times since then I have tried to cross, in dreams, that broken bridge or drifted down that river or got lost in the marshy banks it would be hard to say.

Frances was a child of very decided character & not easy to manage. We had left the Henui & were living nearer the bush section my father had bought & was building a house on. I think we used to give way to Frances very much although there were two younger little sisters Mary & Augusta. One day we did something to offend & displeasure her very much, and she exclaimed ‘Now you have made me cross you will have to please me again. Mamma said so’ and no doubt we had to do our best to please her imperial highness. No doubt it was bad for her. but my dear mother had far too much work to do for her little ones to be able to give special training to one who wanted it more than the others. How she must have worked for us & how she tried to teach us as well. When we went to live in the bush there were plenty of things to excite and amuse us, but for my father, mother & brother it must have been dreadful. The hard work, the disappointments & worries were enough to kill anyone brought up as my parents had been. Father had no natural bent for farming & that was his mistake.

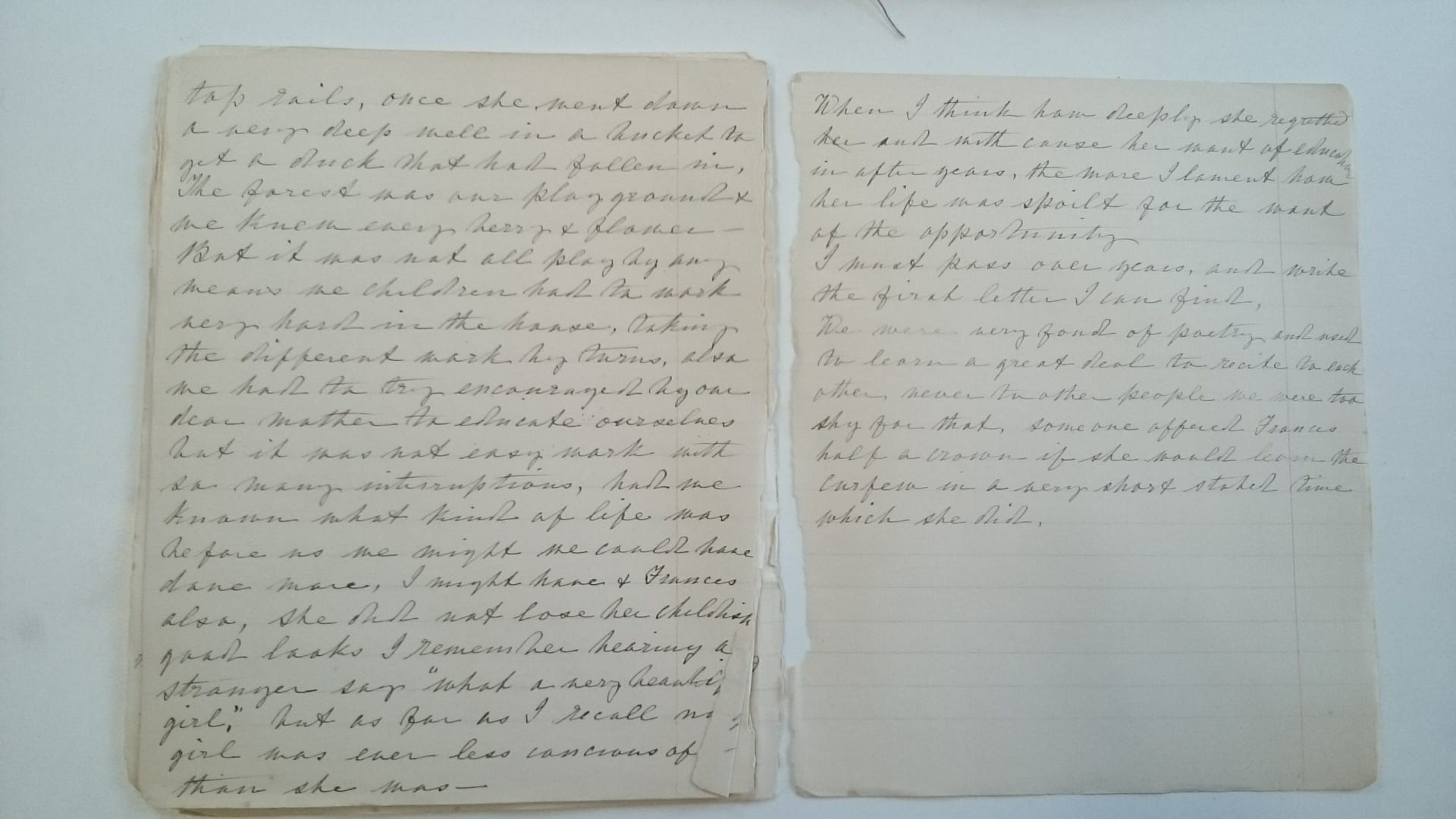

What hardships we underwent and privations but I think we must have been a cheerful lot & got fun and amusement out of everything. We used to swing on the great creepers hanging from the forest trees, climb trees like boys and walk across the clearings from one log & branch to another without touching the ground. Frances could walk all round the stock yard on the top rails. Once she went down a very deep well in a bucket to get a duck that had fallen in. The forest was our playground, we knew every berry & flower – But it was not all play by any means. We children had to work very hard in the house, taking the different work by turns. Also we had to try (encouraged by our dear mother) to educate ourselves but it was not easy work with so many interruptions. Had we known what kind of life was before us we could have done more, I might have & Frances also. She could not lose her childish good looks. I remember hearing a stranger say ‘what a very beautiful girl,’ but as far as I recall no girl was ever less conscious of it than she was. When I think how deeply she regretted and with cause her want of education in after years, the more I lament how her life was spoilt for the want of the opportunity.

I must pass over years, and write the first letter I can find. We were very fond of poetry, and used to learn a great deal to recite to each other, never to other people, we were too shy for that. Someone offered Frances half a crown if she would learn the Curfew in a very short stated time, which she did.