Section 7: January 1889

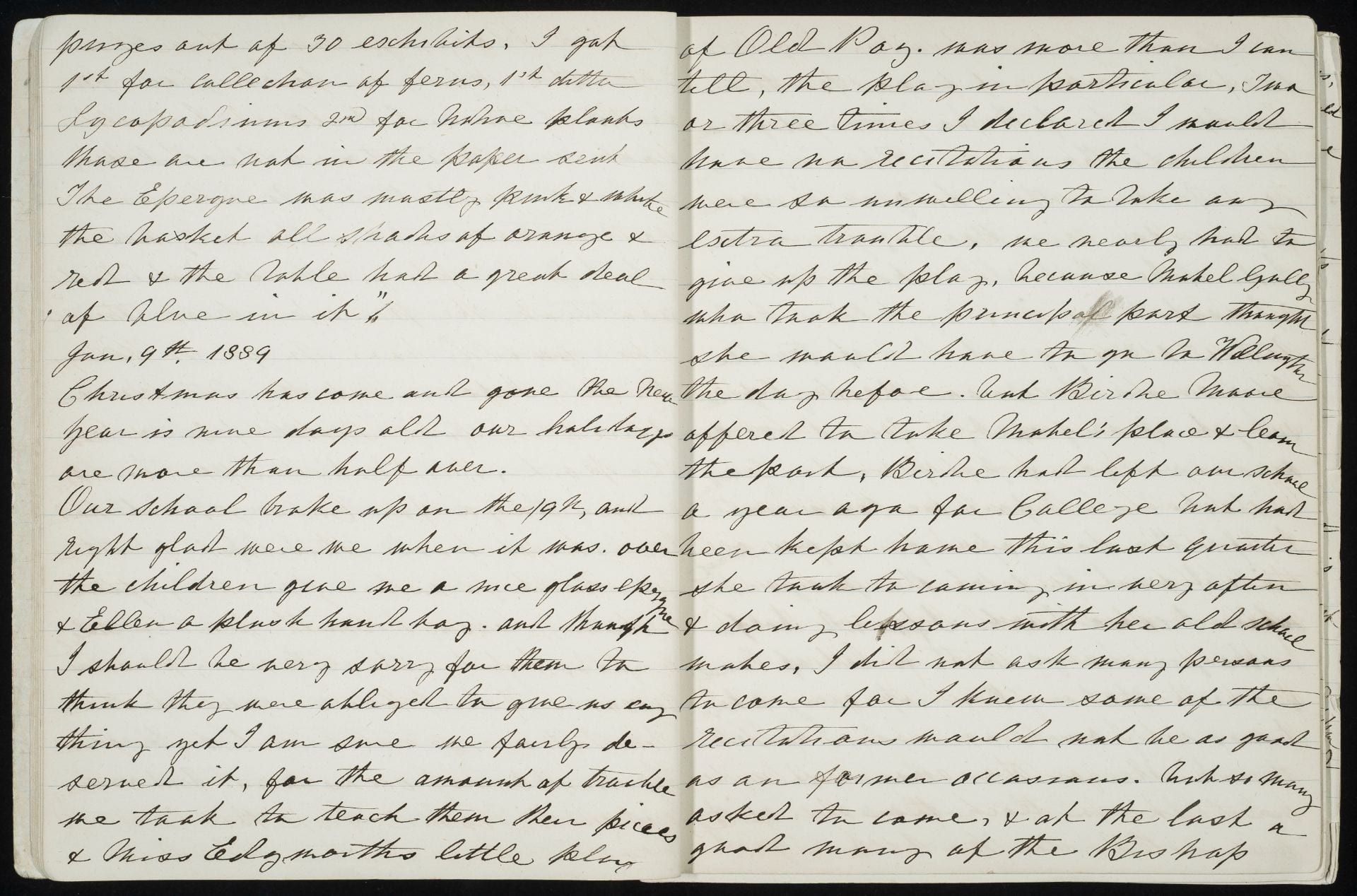

Jan 9th, 1889 [Wednesday]. Christmas has come and gone, the New Year is nine days old, our holidays are more than half over.

Our School broke up on the 19th [December], and right glad were we when it was over. The children gave me a nice glass Epergne & Ellen a plush handbag, and though I should be very sorry for them to think they were obliged to give us anything yet I am sure we fairly deserved it, for the amount of trouble we took to teach them their pieces & Miss Edgeworth’s little play of Old Poz was more than I can tell. The play in particular; two or three times I declared I would have no recitations, the children were so unwilling to take any extra trouble. We nearly had to give up the play because Mabel Gully who took the principal part thought she would have to go to Wellington the day before, but Birdie Moore offered to take Mabel’s place & learn the part. Birdie had left our School a year ago for College but had been kept home this last quarter. She took to coming in very often & doing lessons with her old schoolmates.

I did not ask many persons to come for I knew some of the recitations would not be as good as on former occasions. But so many asked to come & at the last a good many of the Bishop’s School boys crowded round the open door — there was not room for them inside. Lots of the boys brought flowers to decorate the room. Chummy Levien said to his mother, ‘Do give me some flowers for Miss Harris, you know I do like that old schoolroom & I want to go in.’

My children had taken a very great deal of trouble to decorate the room the day before & I got up very early to finish all the arrangements, & put finishing touches a short time before we commenced. I left the door open for a few minutes while I went to fetch the prizes & when I came back I found half a dozen boys with a lot of lovely flowers, sticking them up everywhere. I was very much amused. I had to thank them, turn them out & take down their flowers as it was rather too much of a good thing.

The whole affair went off very well, although some of the recitations were bad & one thing was spoilt because the children were so bubbling over with delight they couldn’t speak for laughing. The play was really exceedingly well done. We were told of one boy who went home & said to his mother: ‘Whatever you do, mother, next year you must not miss Miss Harris’s breaking up. It was really splendid.’

On the 21st, 22nd & 24th we were all hard at work decorating the Cathedral for Christmas and posting & receiving Christmas cards, books etc.

Christmas is always a quiet day with us.

On Thursday Dec 27th, Frances and I went to a large camping out party. Ever since our very successful camping out party last year I had determined to go again if possible. So whenever the Wrights mentioned it I always said I wished we could go again and so by degrees another party was arranged & for the 28th of December 1888. We were told to be ready at 6 a.m. I was up before 5, Frances a little after. I lighted the fire & got breakfast & then Ellen came down, we were quite ready a little after 6, so we went two or three times to see if the coach was at the Wrights’. Then Charlie came to say that all our things were to be carried over to their house & so he helped to carry our numerous packages. Clothes, wraps, bedding, painting materials & provisions for a week for Frances & myself. We had tried hard to keep our luggage within bounds, we wished afterwards that we had taken one or two things more. However, we took good care to take quite our share of provisions.

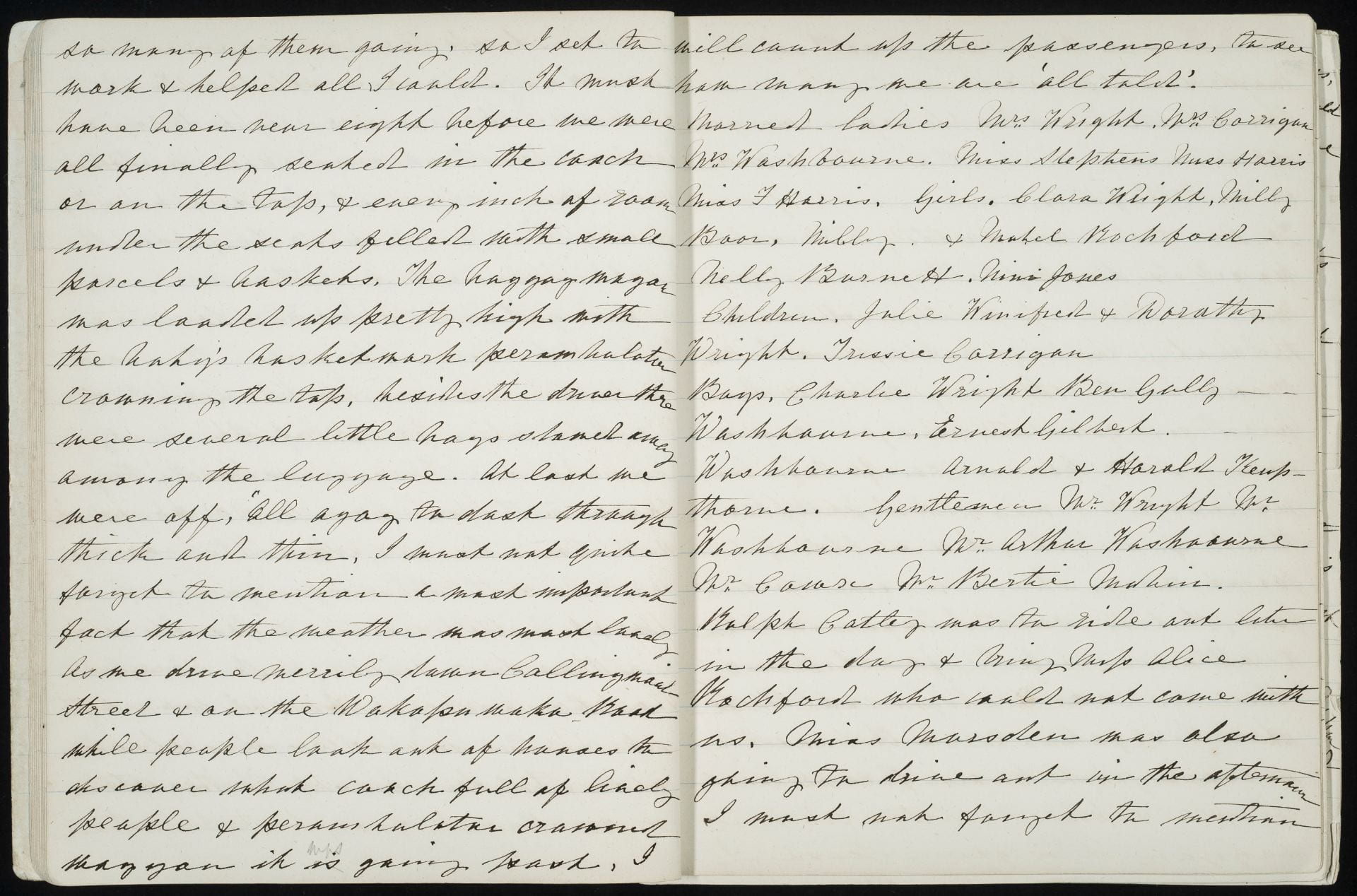

We were getting tired of waiting when the first instalment of the party stopped at our gate, Mr & Mrs Washbourn & Mr A. Washbourn. Then when the coach had arrived we went over to the Wrights’, where most of the party had assembled. There was a pretty big coach with four horses & a wagonette with two horses, the latter was being loaded with the luggage. Such a heap of bundles, bags & packages of all sorts & sizes on the verandah & in the passage, I could scarcely get in to see Mrs Wright & Clara in the kitchen. Lots of things still to be done, as one might expect, so many of them going, so I set to work & helped all I could.

It must have been near eight before we were all finally seated in the coach or on the top, & every inch of room under the seats filled with small parcels & baskets. The baggage wagon was loaded up pretty high with the baby’s basketwork perambulator crowning the top, besides the driver there were several little boys stowed away among the luggage. At last we were off, ‘All agog to dash through thick and thin.’ I must not quite forget to mention a most important fact that the weather was most lovely. As we drive merrily down Collingwood Street & on the Wakapuaka Road while people look out of houses to discover what coach full of lively people & perambulator-crowned wagon it was going past, I will count up the passengers to see how many we are ‘all told.’

Married ladies: Mrs Wright, Mrs Corrigan, Mrs Washbourn.

Miss Stephens, Miss Harris, Miss F. Harris.

Girls: Clara Wright, Milly Boor, Nelly & Mabel Rochfort, Nelly Burnett, Nina Jones.

Children: Julie, Winifred & Dorothy Wright, Trissie Corrigan.

Boys: Charlie Wright, Ben Gully, [Henry] Washbourn, Ernest Gilbert, [Francis] Washbourn, Arnold & Harold Kempthorne.

Gentlemen: Mr Wright, Mr Washbourn, Mr Arthur Washbourn, Mr Caux, Mr Bertie Mabin.

Ralph Catley was to ride out later in the day & bring Miss Alice Rochfort who could not come with us. Miss Marsden was also going to drive out in the afternoon. I must not forget to mention Fred Wright état six months, a very important personage. The Rev. Mr Kempthorne was coming out sometime during the week and perhaps Miss Branfill.

It was quite new country to me when we got to Happy Valley. When it first received that name it must have been a lovely valley, but now with so much bush cut away much of the beauty is gone, in my eyes. We passed many nice farms & comfortable looking houses, & a newly erected pretty church. Most of us got out & walked for some way when we came to a long hill. Soon I began to notice a little more of the forest remaining, then we crossed a river, & a little after passed a gate across the road, which was the division between Happy Valley & the Maori land rented by Mr George Sinclair. Mr Sinclair & Mr Martin of the Maori Pah had most kindly given Mr Wright permission to camp anywhere he liked there or on Pepin Island.

There were some miles of territory to choose from, so Mr Wright rode out one day all over the country to find a suitable spot. He fixed upon a lovely spot not many minutes’ walk from the gate. A grass grown spot, near to the winking river, where the forest had not been cut down.

We were all very glad to get out of the bus and were soon scattered in all directions, having a look at our new abiding place, viewing it from various points. We were especially charmed with the river.

After a while we began to subside into little groups under the trees, some reading, some talking and some trying to sleep, myself among the latter, for we were all more or less tired with the exertion of the last week. I was quite done up & had got a violent headache, and it seemed to me that wherever I moved my shawls & lay down a ray of sunshine would pierce through the trees & shine on my head. While we were resting in the shade the gentlemen were all hard at work putting up the tents. On the right hand under some tall Tawa trees were four tents erected for the ladies & children. On the left hand under the trees two tents were put up for the gentlemen & boys.

On a large open space of ground between the two camps was erected a fly tent to have our meals under. In front of that a large fire was made, strong stakes were driven into the ground & a pole fixed across to hang the billies of water for making tea or coffee. As the tents were put up, the boys were kept hard at work cutting fern, thick layers of which were put all over the floor of the tents to make the beds on. Meanwhile there was a great unpacking of baskets, hampers, tins & opening of bags etc. before our first al fresco lunch could be had, after which there was a general repacking, selecting and sorting up of everything, putting away in secure shady places what was not required for immediate use. Fresh meat was securely tied up in bags and hoisted with ropes half way up a large tree, to be secure from the flies, and everything else had to be kept very carefully covered up. Sand flies and mosquitoes and blue bottles appeared to suppose that we camped there for their especial benefit. I would like to know what they found to subsist upon before we went there!

Frances set to work to [sketch] a lovely bit of the river. Now it is finished it is a lovely little picture. I did not feel able to sketch, not even the next day.

After the lunch things had been put away, there was a great deal of discussion about what tents the different ladies were to occupy, and then their carpet bags & bedding had to be carried into the tents before the dew fell.

We had dinner & tea together at the same time at six o’clock, then those who wished strolled about until it was dark, when all assembled round the campfire for a concert. Most of the party were musical so there were plenty of choruses and scraps of songs and duets, finishing up with some beautiful hymns before we retired to our various tents. We found a large fire burning brightly in front of our tents.

What a making of beds there was to be sure & searching for lost things. As ours was to be the inside bed we went a little before the others came & made it. We were in want of a candle stick, so Mr Washbourn (who seemed to be able to make everything we asked for) made out of supplejack a stick, & stuck in the floor of the tent it did splendidly. It was late before everyone finally settled themselves to rest, I was going to say to sleep, but that appeared far from the minds of the young ladies. Their powers of laughing, talking & telling stories seemed inexhaustible so that it was long before we slept. We slept well when we had the chance, which was very fortunate as it was certainly by a rule of the camp that, ‘The best of all ways, To lengthen your days, Is to steal some hours from the night my dear.’

The birds & the sunshine awoke us next morning. If six ladies going to bed in one tent found it rather awkward it was certainly worse getting up. We had a large piece of forest and a portion of the river allotted to us as strictly our own for the time being. So one after the other with towel, soap & sponge we wandered off to the river to perform our ablutions. When my sister & I were ready for breakfast we found that the gentlemen had done all they could towards getting it ready. We found a number of our party with forks about four or five feet long, made of supplejacks, toasting mutton chops before the fire, and let me add that mutton chops done that way are more delicious than any other way.

After breakfast there were grave discussions about the Commissariat department & so on. Then it was decided that we should take our lunch and walk to Cable Bay. Miss Marsden drove two of the ladies & the baby in her pony carriage. It was rather a rough walk and very warm, but the ferns & trees were beautiful. Mr Wright pointed out a very lovely scene that he hoped I would sketch. We found Cable Bay a very picturesque place, & very civilised as far as the houses & gardens went. We went beyond the Station to the uncultivated part by the sea, there we amused ourselves for a few hours, had our lunch. Frances and Nina Jones sketched, but I could do nothing.

On our return we visited the Cable House. The young men were most kind in explaining and showing us all the wonderful machinery. I had heard many descriptions of the different apparatus and had seen it working on board the Cable ship Hibernia when the cable was first laid, but to most of our party it was quite new and strange. We were noticing the intensely bright flashing of electric light and found that a message had been sent to Sydney, that ‘there were ladies in the room.’ A few more flashes and back came the reply: ‘We wish them a Happy New Year.’ Soon it was time to leave so after thanking the gentlemen and cordially inviting them to our camp, we began our march home. We enjoyed our tea dinner very much. In the evening we had our novel vigorous concert, enlivened by the addition of one or two Cable Bay gentlemen.

Next morning being Sunday, after various plans had been proposed we decided, all but one or two who had to remain in camp, to go to the Maori Pah Church. We had our own clergyman Mr Caux & could have had service in camp but it was certainly better to go to church. It was a long, hot walk & rather rough over the mud flat part. The Maori church was a well built wooden building on a piece of rising ground, before you come to Mr Martin’s house or the Maori Village. A few Maories came to church but as the service was to be in English we did not expect many. Mrs Sinclair and her two children came. After we were all seated some of the gentlemen had to take out the large fern leaves which had been used for Christmas decorations, the leaves were covered with seed and those who sat near were plentifully besprinkled with golden brown dust. Our very youthful looking clergyman gave us a good sermon on prayer. It was the last Sunday in 1888 and to me the service was very impressive from its very simplicity. The walk back was very hot. We were glad to rest when we got to our camp. Round our fire in the evening all the hymns were sung that the singers could remember the tunes of.

On Monday morning, after breakfast, Frances, Nina Jones and I set off to sketch the view from the Cable Bay Road. As we could not sit down on the road, we had to climb up the bank and managed each to find a seat more or less uncomfortable and inconvenient, but the scene was so lovely that we could not give it up, so set to work in real earnest. After an hour’s work I announced my intention of absconding as I could not stand the sun any longer. On our way back I was very much struck by a tall dead tree, where some bush had been felled by the side of the road. I had wandered on by myself so I sat down & began a sketch of that, & got in a good bit before the other two came up.

In the afternoon I began to sketch a fantail’s nest that Mr Wright had found the first day he came. The young people meanwhile were off upon excursions in various directions, it seemed wonderful the amount of walking they could [do], but whatever we did or did not do, the time appeared to fly.

In the evening, New Year’s Eve, the concert was prolonged to a very late — no, early hour of the New Year, but I was too tired to see the Old Year out this year, although if I had been in town I should no doubt have attended the midnight service at the Cathedral. The Rev. Mr Chatterton came out in the afternoon, he brought word that the Bishop & Mrs Suter were coming out the next day.

New Year’s Day, 1889 [Tuesday]. It was suggested at breakfast that if we were to have distinguished visitors, that the camp should put on a festive appearance, so the young people set to work to sweep and tidy everything. They tied large fern leaves to the corners of the fly tent and covered the floor with fern leaves. A log was pushed into position and covered with an opossum rug as a special seat of honour for the Bishop & Mrs Suter. Then they all went off and sooner than we expected the visitors came. I was painting when I heard the carriage. I looked round for Mrs Wright but she was nowhere in sight, only Mr Wright, so we went to receive them and did our best to show them all we could & entertain them until Mrs Wright appeared. By degrees the rest of the party began to appear.

I think the Rev. J. Kempthorne came out that morning, & with Miss Harrison, Mrs Suter’s niece, & Mr Chatterton we mustered a goodly number at lunch. We had kept a plum pudding in reserve for New Year’s Day & Mrs Kempthorne had sent one out. Mrs Suter had also brought some good things, so altogether we had a feast fit for the occasion. I looked after the Bishop & Mrs Suter & I am sure they enjoyed their lunch, they seemed very amused at the scene.

In the afternoon, the Suters, with two or three of the ladies from our camp (Frances was one of them), drove on towards the Maori Pah. On their return they had some tea, & then set off for town. The Bishop told me that ‘it was a long time since he had been to a picnic but he had enjoyed this one thoroughly.’

The next morning some of our gentlemen had to leave, as office work began again. I intended to paint all the morning but Mr Kempthorne asked Frances, Milly Boor & me if we would like to walk to the Bishop’s Peninsula, so we went. To our great surprise when we got there we found old Mrs Worsley, with her daughter Miss Worsley, & her two sons Mr Hankison & Mr Worsley, just coming away. They had driven out from town. It seemed to me wonderful for an old lady of 81 to be able to take such a long drive. I told them to be sure to call at our camp on their way back.

We had our lunch with us so we did not hurry back, but did a little exploring for ferns. On our return we found a lot of visitors at the camp. Mr Hugh Burnett had driven out his mother, Mrs William Atkinson & Mrs G Blackett. Mrs Boor & Mrs Kempthorne also came out to take Milly back with them, and so by degrees our numbers were decreasing.

It seems that some of these last visitors pronounced our camp very untidy & forlorn looking, a remark that struck me with some surprise as it was a thing I had never [thought]. Certainly when I looked at the camp in that light it did look untidy; all yesterday’s decorations had withered with the sun & the fire, & things were lying about rather. Among thirty people, men, women & children, there were sure to be a few careless ones and it was no one’s business to walk round & keep everything in order. Indeed it could not be done, things had to be put wherever it was most convenient to put them. We were all out there for a holiday & rest from work & the less we could do with the better. Still the fact remained that to provide breakfast, lunch, dinner & supper for so many, even with many helpers, was no small work. If we had intended to remain some weeks, things would have been arranged in a more shipshape manner but as it was as long as we engaged ourselves it mattered little.

Mr & Mrs C. Jones drove Miss Stoddart (Artist from Christchurch) out to the Maori Pah, & on their way back took Miss Nina Jones with them. Our concert this evening was better as we had Mr Kempthorne. Before it commenced Miss Marsden told us some of her experiences as one of eleven Red Cross Sisters who were with the Russian Army when fighting with the Turks. Most thrilling & ghastly stories coming from an eye witness and participator affect one in a way that no printed records ever can.

Thursday. In the morning Miss Marsden drove into town & took Mrs Washbourn with her. I went ferning with Mr Kempthorne, he having offered to take the plants into town with him. In the afternoon the Cable Bay young men sent a buggy for some of the young ladies & Mrs Wright, to go to Cable Bay for tennis & afternoon tea. Frances & I went on with our sketches. Mr Kempthorne left in the afternoon. Our evening’s amusements were prolonged until a very late hour, no one wanted to go to bed because it was the last night. Auld Lang Syne, Rule Britannia & God Save the Queen quite failed to close the proceedings. There was a great talk about staying on until Monday. Mrs Wright came to ask me what I thought, she thought that, as everything had gone on well, it was better to leave on the day appointed. Mr Wright would have to leave on Friday & she did not quite like being left sole guardian. I agreed with her, although we would have been most glad of a little more sketching.

Friday. In the morning Mrs Corrigan, Nelly Rochfort & Julie Wright went with me along the road to Cable Bay, & I did a little more to my sketches. In the afternoon three of us went to have a farewell bathe in our lovely river.

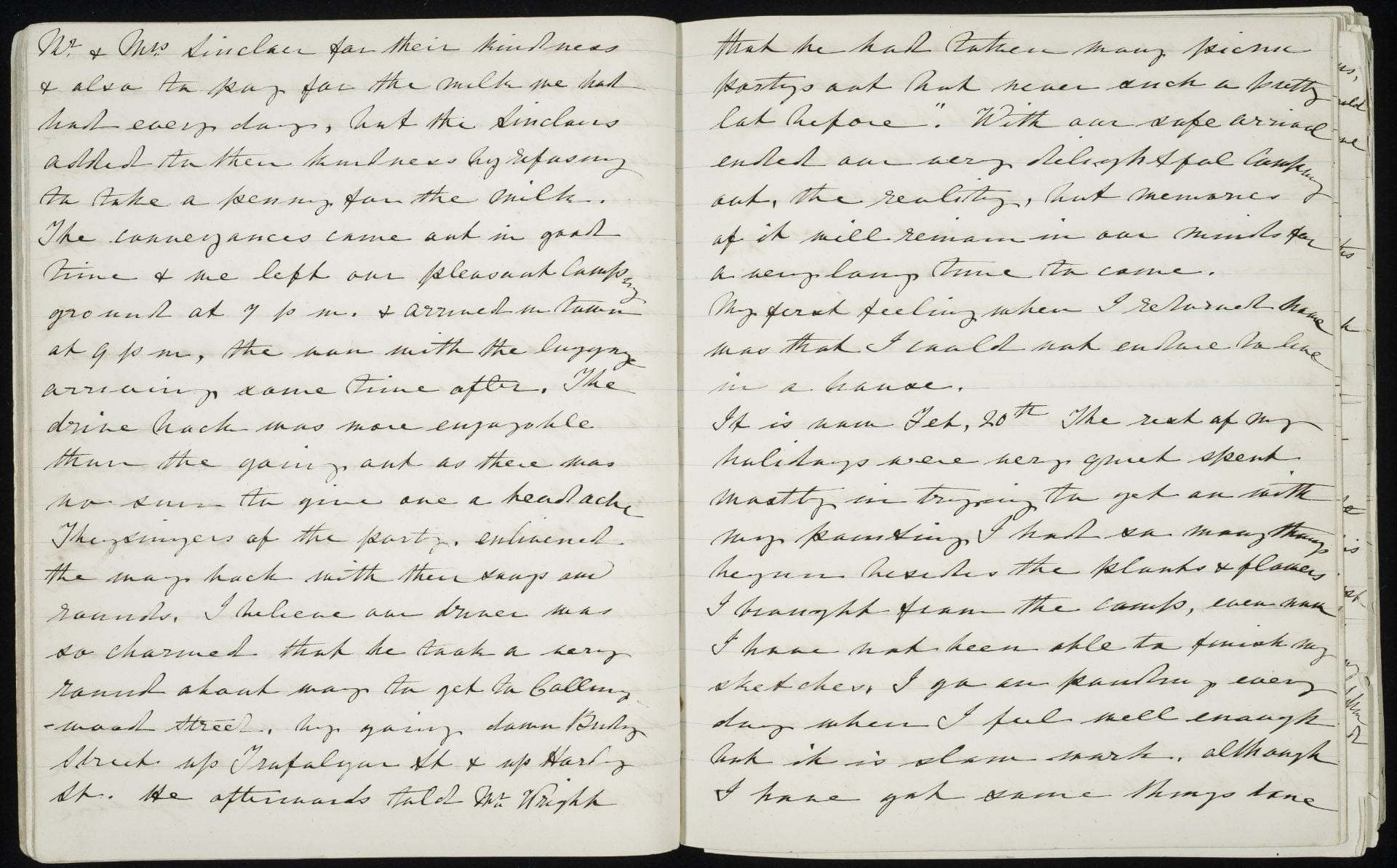

Our camp was soon a scene of packing up, people rushing about to collect their own things, pack them up in baskets & bundles. Mr & Mrs Wright went to thank Mr & Mrs Sinclair for their kindness & also to pay for the milk we had had every day, but the Sinclairs added to their kindness by refusing to take a penny for the milk. The conveyances came out in good time & we left our pleasant camping ground at 7 p.m. & arrived in town at 9 p.m., the man with the luggage arriving some time after. The drive back was more enjoyable than the going out as there was no sun to give one a headache. The singers of the party enlivened the way back with their songs & rounds. I believe our driver was so charmed that he took a very round about way to get to Collingwood Street, by going down Bridge Street, up Trafalgar St. & up Hardy St. He afterwards told Mr Wright that he ‘had taken many picnic parties out but never such a pretty lot before.’ With our safe arrival ended our very delightful camping out, the reality, but memories of it will remain in our minds for a very long time to come. My first feeling when I returned home was that I could not endure to live in a house.

Notes

Jan 9th, 1889 [Wednesday]. Christmas has come and gone

Emily reviews end of year events, including a school break-up and the camping out party she and Frances went on with friends and neighbours 27 Dec 1888-4 Jan 1889. See ‘Camping out beyond Happy Valley’ (19 Mar 2020).

Miss Edgeworth’s little play of Old Poz

Maria Edgeworth (1768-1849) was an Anglo-Irish novelist and educationist who defended female education and wrote stories and plays for children. ‘As the author of six plays for children, Edgeworth is a pioneering figure in the field of Theatre for Young Audiences (TYA). Two of her standout plays for children are 1797’s Old Poz (set in England), with its highly memorable cast of characters, and 1801’s The Knapsack (set in Sweden), in which Edgeworth tries – as in so many of her works – to convince people from all social classes to show greater civic responsibility.’ (Classic Irish Plays)

Birdie Moore offered to take Mabel’s place & learn the part

See section 4 for an earlier reference to Mabel Gully. Ethel Mary (Birdie) Moore (1876-1939) was the daughter of Emily’s neighbours Ambrose and Sarah Moore. She and Mabel were cousins and grand-daughters of John and Jane Gully.

Chummy Levien said to his mother, ‘Do give me some flowers for Miss Harris […]’

Solomon Cecil Levien (1878–1955), sixth son of Robert and Henrietta Levien. James Harkness, retiring headmaster of the Bishop’s School, identifies Chummy in a farewell speech: ‘Amongst the first boys he remembered Nelson Levien as about the first scholar, and all the boys of that family had passed through the school, the youngest — he was almost going to call him “Chummie” (laughter)— having only very recently left to enter an office.’ (Nelson Evening Mail 28 Aug 1895: 2)

Then Charlie came to say that all our things were to be carried over to their house

Surveyor William Charles Wright and his wife Clara moved to Nelson after the death of their eldest son Henry Frederick, aged five years, in Christchurch in 1882 (Star 3 Aug 1882: 2). The Wrights lived in Collingwood St and organised an earlier camping party at Christmas New Year 1887. Their older children Charlie and Clara appear in Emily’s list of campers, along with three younger siblings, Julie, Winifred and Dorothy.

Mr & Mrs Washbourn & Mr A. Washbourn

Henry Philip Washbourn (1846-1937), his wife Clara Emily née Caldwell (1856-1935) and younger brother Arthur Joseph Washbourn (1849-1933). The Washbourns were married in 1874. Their eldest sons, Henry (born 1875) and Francis (born 1877) are among the boys on Emily’s list of campers though she has not remembered their first names, which have been added here.

At last we were off, ‘All agog to dash through thick and thin.’

Emily quotes William Cowper’s comic poem, ‘The Diverting History of John Gilpin’ (1782). It begins:

John Gilpin was a citizen

Of credit and renown,

A train-band Captain eke was he

Of famous London town.

John Gilpin’s spouse said to her dear,

‘Though wedded we have been

These twice ten tedious years, yet we

No holiday have seen.

‘To-morrow is our wedding-day,

And we will then repair

Unto the Bell at Edmonton,

All in a chaise and pair.

‘My sister and my sister’s child,

Myself and children three,

Will fill the chaise, so you must ride,

On horseback after we.’

He soon replied, ‘I do admire

Of womankind but one,

And you are she, my dearest dear,

Therefore it shall be done.

‘I am a linendraper bold,

As all the world doth know,

And my good friend the calender

Will lend his horse to go.’

Quoth Mrs Gilpin, ‘That’s well said;

And for that wine is dear,

We will be furnish’d with our own,

Which is both bright and clear.’

John Gilpin kiss’d his loving wife;

O’erjoy’d was he to find

That, though on pleasure she was bent,

She had a frugal mind.

The morning came, the chaise was brought,

But yet was not allow’d

To drive up to the door, lest all

Should say that she was proud.

So three doors off the chaise was stay’d,

Where they did all get in,

Six precious souls, and all agog

To dash through thick and thin.

Smack went the whip, round went the wheels,

Were never folk so glad,

The stones did rattle underneath

As if Cheapside were mad.

Married ladies: Mrs Wright, Mrs Corrigan, Mrs Washbourn

Emily’s list of campers follows social protocols of the day by prioritising married women, then unmarried women, girls and children. She then turns to the boys and gentlemen of the party. Deborah Corrigan and her daughter Beatrice Alice, born in 1876, are listed without Trissie’s father Cornelius Fooks Corrigan, who was convicted on forgery charges in 1884. He was sentenced to three years in prison and thereafter appears not to have lived with his family. Mrs Corrigan lived with her two children in Nelson in the 1880s. She died in 1894, aged 46. See section 8 for her dealings with the Harris sisters’ dancing class.

Miss Stephens, Miss Harris, Miss F. Harris

Miss Stephens, grouped with Emily (born 1837) and Frances (born 1842), is one of the older woman of the camping out party. She is perhaps Sophia Elizabeth Stephens (c.1836-1901), who died in Nelson some years later:

STEPHENS. — On the 8th inst., at the residence of Mrs Wright, at Auckland Point, Sophia Elizabeth, daughter of the late John Stephens, of London (formerly of Ryde, Isle of Wight), and sister of James Stephens, of the National Bank, Wellington, aged 65. (Colonist 10 July 1901: 2)

Girls: Clara Wright, Milly Boor, Nelly & Mabel Rochfort, Nelly Burnett, Nina Jones

Young women in their teens or early twenties. Millicent Arnold Boor ((1870-1963) was the fourth and youngest daughter of Dr and Mrs Boor. Eleanor Mary (Nelly) Rochfort (born 1872) and her sister Mabel (born 1873) were younger daughters of John and Amelia Rochfort.

Helen (Nelly) Burnett (1866-1944) was the daughter of James and Martha Burnett. Nina Lucy Mary Jones (1871-1926), was the youngest daughter of Charles and Eliza Jones. ‘An amazingly accurate watercolourist, she painted nearly 200 pictures of native flowers and fruits – 30 of which formed part of the New Zealand exhibit at the Wembley Exhibition of 1924 – 25 and most of which are now in the Provincial Museum. She enjoyed painting and sketching with Margaret Stoddart and J H Nicholson and took a keen interest in the Bishopdale Sketching Club (later the Suter Art Society) by serving as Secretary from 1889 – 1925). In addition to this secretaryship, for nearly twenty five years she was Secretary to the Bishop Suter Art Gallery Trust Board.’ (Neale 11)

Children: Julie, Winifred & Dorothy Wright, Trissie Corrigan

Younger sisters, perhaps up to the age of 12.

Boys: Charlie Wright, Ben Gully, [Henry] Washbourn, Ernest Gilbert, [Francis] Washbourn, Arnold & Harold Kempthorne

Benjamin Philip Gully (1872–1959), was the son of Philip Lewis and Mary Elizabeth Gully and older brother of Mabel. Ernest Gilbert was probably a grandson of Thomas and Ann Gilbert, who had six sons when the family arrived in Nelson in 1860 as refugees from the war in Taranaki. Henry Everley Arthur Washbourn (1875-1947) and his brother Francis Irvine (1877-1951) were the eldest sons of Henry Philip and Clara Emily Washbourn (the diary gives only a blank before the last name of each brother). John Arnold Kempthorne (1879-1937) and his brother Harold Sampson (1880-1918) were the eldest sons of Archdeacon John Pratt and Mary Louisa Kempthorne.

Gentlemen: Mr Wright, Mr Washbourn, Mr Arthur Washbourn, Mr Caux, Mr Bertie Mabin

Rev Howard Percival (Percy) Cowx (b. 1866) was an evangelical preacher who married Helen (Nell) Hammond Branfill at Bishopdale, Nelson, in November 1891. The family name was spelled variously Cowx, Caux and de Caux. Frederick Burton (Bertie) Mabin (1870-1961) was the son of Nelson auctioneer John Row Mabin and his wife Fanny Jane, and younger brother of Emerson Mabin.

Ralph Catley was to ride out later in the day & bring Miss Alice Rochfort

Ralph Catley 1867–1949 was the son of James Thomas Catley 1831–1909. and Mary Anne Elizabeth Martin 1838–1880. His sister Maud married Arthur Ashton Scaife in Nelson in 1889. See section 8.

Alice Susan Rochfort (1870-1917) was the eldest daughter of surveyor John Rochfort (1832-1893) and his second wife Amelia Susan Lewis (1844-1942). Younger daughters Nelly and Mabel Rochfort were also part of the camping out party. Alice Rochfort became a qualified nurse whose career included appointments to several hospitals in the North and South islands. In 1906, she resigned her appointment as matron of the Waikato Sanatorium to study maternity care at Clapham Hospital in London for three months under lady doctor Miss McCall. She was a founding member of the Women’s Patriotic league:

To Cambridge ladies belongs the honour of having- inaugurated a movement having for its object the raising of a fund by the women of New Zealand towards the cost of the Dreadnought which Sir Joseph Ward has offered, in the name of the Dominion, to present to the Empire. Miss Rochfort, who is the prime mover in the matter, in the course of a spirited address at Cambridge last week, said that whatever their doubts as to the wisdom of the gift, she believed the women of New Zealand, and men too, would stand shoulder to shoulder and see that the gift, in which their national honour was involved, was given whole-heartedly. The step New Zealand had taken might be far-reaching in the good it would do, and it rested with them all that this patriotic feeling, which prompted Sir Joseph Ward, should be reflected through them, and thus lead up to national good. She hoped that every woman and girl in New Zealand would have an opportunity of showing their interest in this national movement, by subscribing something towards defraying the cost of the ship. It was decided to form a league to be called the Women’s Patriotic League, with Lady Ward as president, and Dr. Mason, Chief Health Officer, central treasurer. The Mayors of the various cities and boroughs, and chairmen of local bodies will be asked to convene meetings of women and girls, and the subscriptions asked for are to be from 1s to 2s. It was also decided to ask editors of newspapers to act as local treasurers, but, while sympathising fully with the object of the League, we would suggest that it might be better to have the movement conducted entirely by women, so that it may be in fact as well as in name, a Women’s Patriotic League. Miss A. S. Rochfort, of Cambridge, is the honorary general secretary, to whom we refer those interested for further information. (Taranaki Herald 13 Apr 1909: 4)

Miss Marsden was also going to drive out in the afternoon

Kate Marsden (1859–1931) was a British missionary and nurse. ‘In 1891 she trekked thousands of miles across Russia to help Siberian leprosy sufferers. On her return she became one of the first women to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and for a while was feted for her adventures and able to raise significant funds to aid the plight of the lepers. But the veracity of her journey was called into disrepute, as well as her management of the funds she was raising, and as a result of a smear campaign led by American translator Isabel Hapgood, KM was unable to ever really restore her reputation or succeed at any other philanthropic projects she initiated.’ (Kate Marsden Victorian explorer Extraordinaire). Miss Marsden was in New Zealand 1885-1889, where her professional activities were at first commended and then called into question after her Siberian journey. An early newspaper report introduces the woman Emily Harris and her fellow campers listened to with rapt attention at Happy Valley:

The Colonial Secretary has, on the recommendation of Dr. Grabham (Inspector of Hospitals), appointed Miss Kate Marsden to the position of Lady Superintendent of the Wellington Hospital, vacant by the retirement of Mrs. Kissling. Miss Marsden is a young lady aged 26, who recently arrived in Auckland from England, and possesses the highest testimonials of qualification for the office to which she has been appointed. She was trained at the London Evangelical Deaconesses’ Institution at Tottenham and at the Westminster Hospital. She served as a nurse in the Institute’s detachment during the Russo-Turkish war, and was four months in Bulgaria at that time. She has since filled the position of assistant superintendent of the Woolton Convalescent Institution, and on resigning that office was the recipient of a very handsome present and testimonial from the authorities and officers. (Evening Post 1 Apr 1885: 3)

See ‘From Happy Valley to Siberia: Miss Kate Marsden’ (7 May 2020)

It was quite new country to me when we got to Happy Valley

Happy Valley is the settlement north of Nelson now known as Hira. Apparently the name Happy Valley was originally an ironic one, given because none of the settlers there could get on with each other. Researcher Anne McFadgen describes the area and some of its history:

From Nelson the road travels northeast along the coastline through Wakapuaka for quite some distance before heading inland to Hira, then across country out to the coast at Cable Bay. Hira was part of a Native Reserve ceded to local Māori, which included part of Pepin Island. Pepin Island is connected by a narrow causeway across Cable Bay to the mainland. Although there were European settlers there, in Emily’s time this area was in tribal ownership, the head of the tribe being a married couple of aristocratic Māori descent – Hemi & Huria Mātenga, also known as James & Julia Martin. Hemi Mātenga would have been the Mr Martin who Mr Wright consulted with. The Mātengas are associated with the rescue of sailors from the ship Delaware, which was wrecked in 1863 in what is now known as Delaware Bay. Julia Martin was particularly praised for her courage and dubbed Nelson’s Māori ‘Grace Darling.’ She was an imposing woman of strikingly handsome appearance. The Mātengas were closely connected to the Church of England – in fact both attended an early school for Māori in Motueka run by the Anglican Church, and they were known for their hospitality. (Email to Michele Leggott 14 Mar 2020)

Hūria Mātenga was born at Whakapuaka (near Nelson) probably some time between 1840 and 1842. She was named Ngārongoā Kātene at birth, but was also known as Ngā Hota and, in later life, as Hūria Mātenga. Of Te Āti Awa, Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Toa descent, she was able to trace her genealogy back to an ancestor in the Tokomaru canoe. Her paternal grandfather was Ngāti Tama leader Te Pūoho-o-te-rangi, a renowned warrior. In contrast, her parents, Wikitōria Te Amohau of Ngāti Te Whiti and Wiremu Kātene Te Pūoho were followers of the pacifist teachings of Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III and Tohu Kākahi. They were the leaders of the settled community at Whakapuaka. In 1858 Hūria made an arranged marriage to Hēmi Mātenga Waipunāhau. There were to be no children of the marriage, but they had one adopted daughter named Mamae. Hēmi Mātenga was the son of Metapere Waipunāhau of Kapiti, and George Stubbs, a whaler and trader, and was a substantial landowner in the Waikanae area. The standing of both families was reflected in the large party of Māori and Pākehā dignitaries who attended the wedding ceremony in Christ Church, Nelson, on 7 or 8 September. (DNZB)

Mr Sinclair & Mr Martin of the Maori Pah had most kindly given Mr Wright permission

George Bell Sinclair (1849-1923), surveyor and farmer, married Rebecca Lee Hodgson (1851-1940) in Nelson in 1875. The Sinclairs had three children: Norman (1875-1876), Kenneth (born 1877) and Isabel Madeline (Madge) (1878-1937). Rebecca Sinclair’s 1932 memoir describes the family’s town life in Nelson and their subsequent move to the farm near Wakapuaka Pā:

We lived happily there for several years but George had an offer to go on the land and as he always got to logger-heads with the chief surveyor Mr Browning, a fussy didactic little man, he decided to try farming.

We went out to the Pah when Ken was about six and Madge a year younger and were there for seven years. George was entirely happy. We both worked from early morning to dewy eve and were worse off when we gave it up than when we started. Prices for cattle and butter were ridiculously low. We never had any money except for absolutely necessary things and yet we were happy. It was a beautiful locality a mile or two from Cable Bay. The Maori Pah proper was about half a mile further on and reached at low tide by a beach track and at other times a bridle track through the glen. […] We got to know and like all the Maoris Including Jim and Julia Martin who were then surrounded by a clan of which they were the heads, and a happy busy lot they were. They were a most intelligent fine set of men and women and our firm friends. George was quite familiar with the Maori language and always talked it with them. They told him he had the Maori tongue. They were most observant of the English people and manners and were quick to comment on any lapse.

‘That the best of all ways, To lengthen your days, Is to steal some hours from the night my dear.’

Emily quotes from ‘The Young May Moon,’ a traditional folk song published by Thomas Moore (1779–1852) in his Irish Melodies.

Then awake! — the heavens look bright, my dear,

’Tis never too late for delight, my dear,

And the best of all ways

To lengthen our days

Is to steal a few hours from the night, my dear!

Then it was decided that we should take our lunch and walk to Cable Bay

The Cable Bay Telegraph Station opened in 1876 when New Zealand was linked to the Eastern Extension Telegraph Company cable connecting Sydney to London. Emily mentions seeing the telegraph apparatus working on board the cable-laying ship Hibernia at the time.

The settlement at Cable Bay grew as the demand for telegraphic services increased. By 1888 there were 14 staff, including a superintendant, cable and telegraph men. A press man had the job of ‘filling out’ the international press briefs and sending them on to newspapers. A second cable was laid in 1890, by which time 17 staff and their families lived at Cable Bay. By all accounts, the community enjoyed good relations with nearby neighbours, Huria and Hemi Matenga, and there was plenty of on-station fun, with a billiard room, tennis courts and water-related activities. […] The Cable Bay link was re-routed to Titahi Bay in 1917, with an underground cable to the Eastern Extension Company’s offices in central Wellington. The staff from Cable Bay were relocated to Wellington overnight on 22 August, 1917 and it was the end of an era for the small community. (The Prow)

Mrs Sinclair and her two children came

Ken Sinclair, aged 11, and his sister Madge, 10.

The Rev. Mr Chatterton came out in the afternoon

Reverend Frederick William Chatterton (1860-1936) married Anne Hill (1852c-1946) in Nelson in 1899. They had one daughter, Theodora Anna Chatterton (1901c-1970), who married Morgan Douglas Laurenson. From his obituary:

Born at Tamworth, England, in 1860, Archdeacon Chatterton was originally intended for a commercial life and with that end in view entered Lloyds’ Bank, in which he served in London and the provinces for seven years. His call to the Church came, however, after hearing a sermon by Bishop Suter, of Nelson, who was then preaching in England. Prompted by that call he came to Nelson in his early twenties and there studied for the ministry, his first appointment being as chaplain to Bishop Suter. After his ordination Archdeacon Chatterton was appointed vicar of All Saints’ Parish, Nelson, where he served for 18 years. During this ministry he interested himself in the Maori people and worked among them, with the result that although offered the bishopric of Nelson he declined that high office and accepted a call to the charge of the Terau Theological College at Gisborne, where he felt he could do greater service. This position he held for 17 years, and during that period was responsible for training the majority of the Maori clergy of the Church of England, among them being Bishop Bennett, present Bishop of Aotearoa and the first Maori bishop. It was but natural that in such a position as principal of a Maori theological college Archdeacon Chatterton should become an accomplished Maori linguist. He was able to preach fluently in Maori and had probably a greater grasp and understanding of Maori mentality than is given to the majority of Europeans who can speak the language. (NZ Herald 18 July 1936: 15)

Miss Harrison, Mrs Suter’s niece,

Margaret Annie Harrison (1856-1947) was the daughter of Edward Francis Harrison and niece of Amelia Damaris Suter, nee Harrison. She was born in Calcutta, the eldest of 12 children and lived most of her life in England. She visited New Zealand in 1888-89, staying with her aunt and uncle at Bishopdale before returning to England and a nursing career as ward sister at the London Hospital. Margaret Harrison was among those who doubted the credentials of Miss Kate Marsden (p. 328) and her claims to have been a nurse in the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78. Our thanks to UK researcher Kate Marsden for supplying biographical information.

See section 8 for Margaret Harrison’s interest in private theatricals and section 9 for her letter to Emily Harris concerning a portfolio of botanical drawings she was to have shown to Lady Onslow during the Vice-Regal visit to Nelson in 1889.

To our great surprise when we got there we found old Mrs Worsley

Caroline Cust (1808-1891) was the second wife of Henry Francis Worsley (1806-1876), by whom she had two children, Emily Louisa Worsley (1847-1927) and Frederic Worsley. Caroline had three sons from her first marriage, one of whom, Donald Hankinson, married his step-sister Catherine Mary Worsley.

Mr Hugh Burnett had driven out his mother, Mrs William Atkinson & Mrs G Blackett

Hubert Burnett (1861-1941) was the son of James and Martha Jane Burnett, who was widowed in 1872. Hugh married Edith Johnston Boor in 1888. Eliza Atkinson, née Ronalds (1840–1915), was the widow of William Smith Atkinson (1826-1874), whom Emily would have known from Taranaki. Mrs G Blackett may be Elizabeth Charlotte Adams (1853-1916) who married John George Blackett in Nelson in 1879 and was widowed in 1885.

Mr & Mrs C. Jones drove Miss Stoddart (Artist from Christchurch) out to the Maori Pah

Charles and Eliza Jones were the parents of artist Nina Jones, who was 18 at the time of the camping trip. Her friend Margaret Olrog Stoddart (1865-1934) was a noted Canterbury flower painter in the 1880s.

Full Navigation

Section 1: August 1885

Section 2: September-November 1885

Section 3: January-March 1886

Section 4: March-July 1886

Section 5: August-November 1886

Section 6: August-December 1888

Section 7: January 1889: You Are Here

Section 8: February-August 1889

Section 9: September-October 1889

Section 10: November-December 1889

Section 11: January-February 1890

Section 12: August 1890-February 1891