By Dasha Zapisetskaya

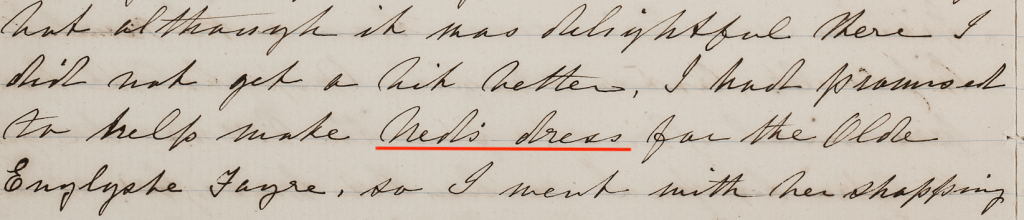

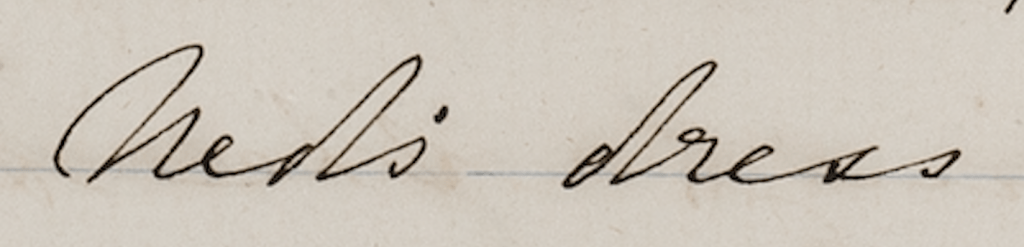

Transcribing a handwritten diary is like doing maths homework; you might whizz through three or four pages before becoming completely stumped by one little problem. This is exactly what happened as I worked through Emily Harris’s account of her visit to a friend in November 1885. ‘I stayed a few days with Mrs Buckeridge,’ Emily writes, ‘but although it was delightful there I did not get a bit better, I had promised to help make…’

Then things stopped adding up, and the next word was a complete mystery. It was clear that Emily had promised to make somebody’s dress for the upcoming Olde Englyshe Fayre, but whose? The 1979 transcriber who worked on Emily’s diary before me had written ‘Bet’s [?]’; forty years on, and I had little to add except another question mark. Tentatively, I tried ‘[bed’s?]’ and moved on, hoping that someone else would know or that an answer would present itself later in the diary.

The word, which morphed further into a cryptic squiggle the more I looked at it, was also an enigma for the rest of the team. We decided that, instead of using the name as a clue to the person, we would use the person as a clue to the name, and I began my search for the Buckeridge family.

I found George and Elizabeth Sarah Buckeridge, the former conveniently appearing on the Nelson electoral roll for 1885-1886. One of their daughters, Frances Isabella Buckeridge, born in 1860, seemed a potential candidate, if we decided that Emily had written that she had ‘promised to help make Bel’s dress for the Olde Englyshe Fayre’ in 1885, when Frances Isabella was 25.

This was pretty good going. Then we encountered the problem of young Lee Buckeridge, who appears in the diary in October the following year, going on a picnic with Emily and others:

We gave ourselves one holiday, I got up a picnic to get some clematis, our party consisted of Mrs S.B. White, Miss Branfill, Clara Wright, Myra Mabin, Frances & self. I almost forgot Lily Burton. The ladies were to go at eleven a.m. & the gentlemen to follow at two p.m. as they could not come before. They were Mr Redgrave, Mr Worsley, Mr F. Smith, Emerson Mabin & Lee Buckeridge. (17 Oct 1886)

Who is Lee Buckeridge? George and Elizabeth had two sons, Edward William and George Henry, who would have been 22 and 19 in 1886, old enough to be considered gentlemen, but, however you look at it, neither name quite shortens to Lee. Either we had the wrong family, or there was another set of Buckeridges in Nelson.

A look into George Buckeridge’s history uncovered a younger brother, Henry John Buckeridge, and his son, Leopold Buxton Buckeridge, born in 1867 and 19 at the time of the picnic! We assumed that Leopold (Lee) Buckeridge was visiting his uncle George in 1886, and happened to also come along on the picnic, as his father, Henry John, did not appear on Nelson electoral rolls of the period.

But things were still not falling into place as we had hoped. Our attempts to decipher the name of the owner of the dress Emily helped make produced different results each time someone looked at the passage. The suggestions still included ‘Bet’ (George and Elizabeth had a daughter called Elizabeth Anne, but her birthdate was elusive). ‘Bel’ was still on the table, though the initial letter did not look much like an uppercase B, and the last letter was more like Emily’s d’s than anything else. This is why I initially hazarded ‘bed,’ which of course does not make sense. ‘Ned’ seemed orthographically plausible, but since we were dealing with a 19th-Century English colonial settlement, we assumed we were looking for a little girl or a young woman. Could she be Bet, Bel, or perhaps Bid (short for Biddy, a diminutive of Elizabeth)?

Another problem was holding us back. On 24 May 1886 Emily had written: ‘I went with Mrs Buckeridge & her three sons & a few others for a picnic up the Dunne Mountain line just above the Glen.’

Three sons? This did not fit Elizabeth Sarah Buckeridge, for whom we could find only two sons, and it seemed unlikely that Emily was mistaking Lee for a third son. Which Buckeridge family was Emily friends with, and whom did she help with the dress for the Fayre? Henry John and Matilda didn’t have even one daughter who could be Bet, Bel, or Bid. They did however have three sons. Did Emily know one Buckeridge family or two? The search had to continue.

Leopold, who was our first hitch, led us to the solution. He had two siblings — an older brother called Henry, born in 1866, and a younger brother called Edmund. Here was our Ned, born in 1877, aged 8 at the time of the Olde Englyshe Fayre, and young enough to wear a traditional children’s smock costume. In other words, a ‘dress.’

Having found Ned Buckeridge, we began to work backwards in our story. It must have been Matilda Buckeridge with whom Emily was staying in November 1885. It was Matilda’s son who wore the dress Emily helped make while she was staying there. It was Matilda and her three sons who picnicked with Emily in May 1886. Then we discovered why Henry John Buckeridge did not appear on the Nelson electoral rolls for 1886 alongside his brother George.

In early 1881, Henry John Buckeridge drowned near Moutere while trying to save his son, Leopold Buckeridge. Newspaper reports detailed the tragedy:

Yesterday afternoon several members of the family went on a little boating excursion, and on their return all safely landed with the exception of one of the boys, Mr Buckeridge’s second son we learn, and who would be about thirteen years old, tried to pull the canoe ashore, but the waves washed him off his feet, and he was carried out a little way, clinging to the boat all the time. He then managed to get into her. Mr Buckeridge, who, we believe, was a good swimmer, at once entered the water and swam after the boat, but all his struggles to overtake and rescue his son were futile. He persevered however till his strength gave out, and he had to succumb.

[…]

Since writing the above we learn that the body of Mr Buckeridge was recovered two hours after the accident, and that although efforts to restore animation were continued for four hours, they were unavailing. (Colonist 27 Jan 1881: 2 sup)

Matilda Buckeridge and her sons Edmund, not quite 4, and Henry, almost 15, watched helplessly from shore as Henry Senior disappeared and the boat carrying Leopold was swept into rough waters. Henry Junior begged the men who had recovered his father’s body to rescue his brother. Three men volunteered to go and look for the drifting boat and Leopold was saved:

At a quarter to four that afternoon they discovered the object of their search, having sailed straight to it. The canoe was some fourteen or sixteen miles from land, opposite Pepin’s Island. After using the utmost caution, they succeeded in getting the boat alongside the canoe, and threw a rope right over the boy, to which he clung most tenaciously. After hauling the boy into their boat, the weather was so tempestuous that they were obliged to let the canoe go adrift. The brave boy, although only some twelve years of age, while in the canoe had been trying to make himself some paddles out of a piece of wood, also to mend the rowlocks of the canoe. In doing this work he had lost a costly pocketknife, and he expressed to his rescuers a fear that his father would be displeased thereat. Poor little fellow, he did not know then of his far more serious loss, that he was fatherless. (Colonist 27 Jan 1881: 2 sup)

Leopold’s heart-breaking anxiety is just as poignant now as it was then, and our knowledge of Matilda’s loss gives a new significance to her appearances in Emily’s diary. Although little detail is given about her situation, she was clearly a key figure in Emily’s social life in Nelson. On 21 May 1886, Emily reports: ‘Frances & I went to a dance given by Mrs Buckeridge,’ and within a week Mrs Buckeridge and her sons join Emily and others for the Dunne Mountain picnic already mentioned. In the years after her husband’s death, Matilda Buckeridge built a life for herself and her children that was full of friends, neighbours, and community activities.

The Olde Englyshe Fayre was one such activity. Emily writes that ‘the Maypole dance [which she and her sisters organised] was without doubt the greatest attraction, it had never been seen in Nelson before.’ ‘Master Buckeridge’ is listed in a newspaper report quoted by Emily as one of the ‘little people all arrayed in the prettiest of costumes’ in the dance. Emily and Matilda’s work has paid off. Emily continues quoting the Nelson Evening Mail of 2 Dec 1885:

Of the dancing, which commenced with Sir Rodger de Coverley, it is impossible to speak in too high praise, for it was simply perfect. In all there were twelve figures, some of them most intricate & complicated and all were gone through without the slightest hesitation or a single mistake. Colonel Pitt & Major Webb have received, & deservedly so, much kudos for the efficiency which the Nelson Volunteers have attained in battalion drill, but we may fairly say that no movements were ever executed in the Botanical Reserve with greater precision than were those around the Maypole last night under the direction of the Misses Harris . . . The applause was frequent & enthusiastic.

There is an undated photograph in the Tyree Studio collection at Nelson Provincial Museum labelled ‘Unnamed Maypole Dancers’ and showing a group of children in costume with two women who could be their instructors. The woman in dark clothing on the left looks like Emily Harris. There is a boy in the front row in a farmer’s smock who could be Ned Buckeridge. The children look a little grim in their festive outfits, despite the high praise for their dancing that has recently appeared in the paper. But then, photography of the day required stillness on the part of its subjects as the long exposure time clicked by. The merriest of Maypole dancers would have found it hard to keep a smile looking natural. Have a look for yourself.

Lead writer: Dasha Zapisetskaya

Research support: Michele Leggott, Brianna Vincent, Makyla Curtis, Ricci Van Elburg