By Michele Leggott and Brianna Vincent

Unnamed Daughter

7-12 March 1841

Before my confinement I felt very unwell for some weeks, I wanted the frequent doses of Castor Oil as was my custom in England, but from the scarcity of it on board I could not have it, so I was induced to take two pills Emma gave me marked strong aperient; it brought on diarrhoea from which I suffered violently for eight days; the surgeon said nothing but bringing on the labour would save my life; in less than an hour after a fine little girl was born. (Sarah Harris to father William Hill and sisters. Off the shores of Taranaki, 20 April 1841)

Sat 6 Mar 1841: ‘Feel annoyed at Mrs Harris, who being very near her confinement, has brought on a dangerous illness by taking Morrisons Pills.’

Sun 7 Mar: ‘Mrs Harris confined with a girl and doing better than I could expect. No service this morning, the parson acting as midwife.’

Fri 12 Mar: ‘Mrs Harris’s infant which was prematurely born on Sunday died this morning – of no apparent cause.’

Sat 13 Mar: ‘The infant was dropt into the sea this morning at six, sewn up in a piece of canvas.’ (Dr Henry Weekes, Journal of Common Things. Puke Ariki. ARC2001-129)

Sarah Harris was pregnant with her fourth child when the William Bryan left Plymouth for New Zealand 19 November 1840. Corbyn (5) and Katie (18 months) were both dangerously ill on the voyage; Emily (3) was by her mother’s account well all the way. Sarah’s confinement, brought on by injudicious use of some strong laxative pills given to her by her sister Emma Hill, marked the start of a disastrous week for the Harris family. Sarah was ill and unable to feed her newborn daughter, who died six days after birth. The child was never forgotten by her mother, whose accounts both in 1841 and 1871 testify to the impact of losing her unnamed daughter and to her horror of the burial at sea recorded by ship’s surgeon Dr Henry Weekes. Weekes’ journal supplies not only references to the birth and death of the Harris child but other comments on ship life plus celestial and marine observations. From his noting of the ship’s latitude and longitude before and after the child’s birth and death, it is possible to calculate roughly where the burial of Saturday 12 March 1841 occurred as the ship approached New Zealand from southern latitudes below Tasmania.

From Sarah Harris’s writing about her unnamed child:

The weather was very warm before and after crossing the Line and dear Corbyn suffered much from it, he was taken ill about the 7th Dec. of a slow fever and continued very ill for more than a month. I was fearful he would be starved as he did not eat anything for 8 or 9 days, but it was favourable to the disorder; as soon as he was better, baby was so ill as to cause everyone to think she would not survive the voyage. Change of food recovered her, but she was ill to the end of the voyage & I was from my own illness obliged to give her up to the woman who attended me all the time. She proved a mother to her.

Before my confinement I felt very unwell for some weeks, I wanted the frequent doses of Castor Oil as was my custom in England, but from the scarcity of it on board I could not have it, so I was induced to take two pills Emma gave me marked strong aperient; it brought on diarrhoea from which I suffered violently for eight days; the surgeon said nothing but bringing on the labour would save my life; in less than an hour after a fine little girl was born my illness continued, the ninth day after everyone thought I was dying two women remained with me at night, and on that night Mr Weeks gave me up. About the middle of the night the nurse sent for him I felt as if I was going fast I prayed I might be restored and by the tender mercy of the Almighty I was so.

The surgeon gave me Port Wine with little water, I was very ill for a month and during the time we lay in Cloudy Bay I was too ill to get out of bed and remained on board for several days after all had landed. Edwin and the children went on shore.

We sleep in a place that many English would not put their horses in, with the rats running over our heads. I began to recover as soon as I got on shore and poor Kate also; I could not nurse the baby but a Mrs Crocker did for me, but for want of proper nourishment died five days after her birth & was buried at sea poor little thing she only wanted a mother’s care. (Sarah Harris to father William Hill and sisters. Off the shores of Taranaki, 20 April 1841)

I was taken very ill with Diarrhoea just before I expected my fourth baby. My illness was fearful & the weather was very stormy. I clung with all the strength I could get to prevent myself from being thrown out on the floor. In the midst of dreadful suffering my babe was born, a fine Girl. The Dr said nothing could save me but the birth of the child. Four days after I had by my wish the babe brought to me for the first time. I caressed her with the fondest affection when she began to seek for the natural nourishment, but alas there was none & I gave her back to the nurse. I was looking at her on the nurse’s lap when I heard her tell someone to send the Dr. He came & said the child is convulsed & was dying. Oh God had I killed my baby with too much love, or was it the want of food (for there was a great scarcity). Such thoughts as those dwelt on my mind so much that all hope of my recovery seemed hopeless.

The second night my dear husband was sitting by my bed holding my hand. We were both quiet, for some time there when I said, There, did you not hear? They are consigning our darling to the deep. No, he said, they are not, the baby is laying on the bed the nurse sleeps in. (Sarah Harris to father William Hill and sisters. New Plymouth, May 1841)

Notebook (90-91): ‘The dear baby was a fine healthy child & the great trouble was how was she to be nourished. I had none & baby’s food was not to be found among the ship’s stores & there was only one kind friend who had been nursing her child more than twelve months offered to nurse mine twice a day. It was gratefully accepted & on the forth day after she was born I had her brought to me as I had been too ill to have her before scarcely expected to recover. To have her in my [arms] to caress and admire with all a mother’s love was joy unspeakable, but saddened by the knowledge that the nourishment she sought could not be found. On giving her back to the nurse, I was shortly afterwards struck by the look of alarm the nurse gave. She sent for the Dr who said when he looked at her she is convulsed & was dying.

[the rest of this page features crossed out sentences, and pen has been written over pencil]

The death of a baby is always a great sorrow to a mother but the knowledge that my sweet babe was to be consigned to the deep intensified my grief so much as to throw me back so much that little hopes of my recovery remained

but the knowledge that my sweet babe was to be buried at sea intensified my grief & threw me back that there was little hope of my recovery. (Notes, Sarah Harris to father William Hill and sisters. New Plymouth, May 1841)

Image 1

Image 2

Image 3

According to the dates and (often partial) coordinates in Henry Weekes’ diary, the William Bryan would have been travelling along the 44 degree line of latitude, visible on this map underneath Tasmania, on 27th February. Sarah’s unnamed daughter was born on the 7th of March. On the 10th of March the ship was further south of Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) but no coordinates are provided. On the 12th, the unnamed Harris daughter passed away and was buried at sea on the 13th. The closest coordinates given are several days later, on the 16th and 17th (pictured), approaching the top of the South Island.

Dr Henry Weekes (1804-94) made several manuscript versions of his voyage to New Zealand and the year he spent in the New Plymouth settlement. When the diary was published in 1940 as part of The Establishment of the New Plymouth Settlement in New Zealand, editors Rutherford and Skinner presented the passage from late February to the sighting of land in Mid-March 1841 as follows:

27th. [Feb] (Therm. 53 degrees, lat. 44 degrees S.) [101 days out from Plymouth.]

March 2nd. The “Southern lights” (Aurora Australis) have been playing beautifully this evening. It was cloudy at first and appeared like moonlight, but as soon as it cleared up we could see the broad sheets of electricity flickering up from the south with a pale yellow light.

7th. (Sunday.) One of the passengers is now in great danger from taking a quantity of Morrison’s pills; and for dysentery too! Mrs. Harris confined with a girl and doing better than I could expect. No service this morning, the parson acting as midwife. The sea is beautifully luminous, a long streak of phosphorescence being left in the ship’s track. Every now and then a large ball of white light passes the ship on either side. These are phosphorescent medusae or blubber fish.

10th. We are now off Van Diemen’s Land, but are too far south to see any part of it.

12th. Mrs. Harris’s infant, which was prematurely born on Sunday, died this morning – of no apparent cause.

13th. The infant was dropped into the sea this morning, sewn up in a piece of canvas.

16th. (Therm. 62 degrees, lat. 40 degrees 38 minutes, long. 169 degrees 42 minutes.) We are now all anxiously expecting to see land tomorrow morning at day-break. Indeed, I distinctly smelt a peaty odour about 4 p.m. and a little terrier on board has been capering about and sniffing in the breeze from over the ship’s side with evident delight. A change is now desirable, for all our stories, riddles, and puns, are become exhausted, the new ones being generally very bad indeed; but perhaps the bad ones served the purpose better, for they raised a louder laugh. We have all endeavoured to study something useful, Mr. King and myself have learnt some Spanish grammar and some geometry, but it is impossible to do much in a rolling ship, the mind being as much unsettled as the body. We have continued our after-tea rubbers without an interruption (Sundays ex.) since our departure – Saturday nights as usual.

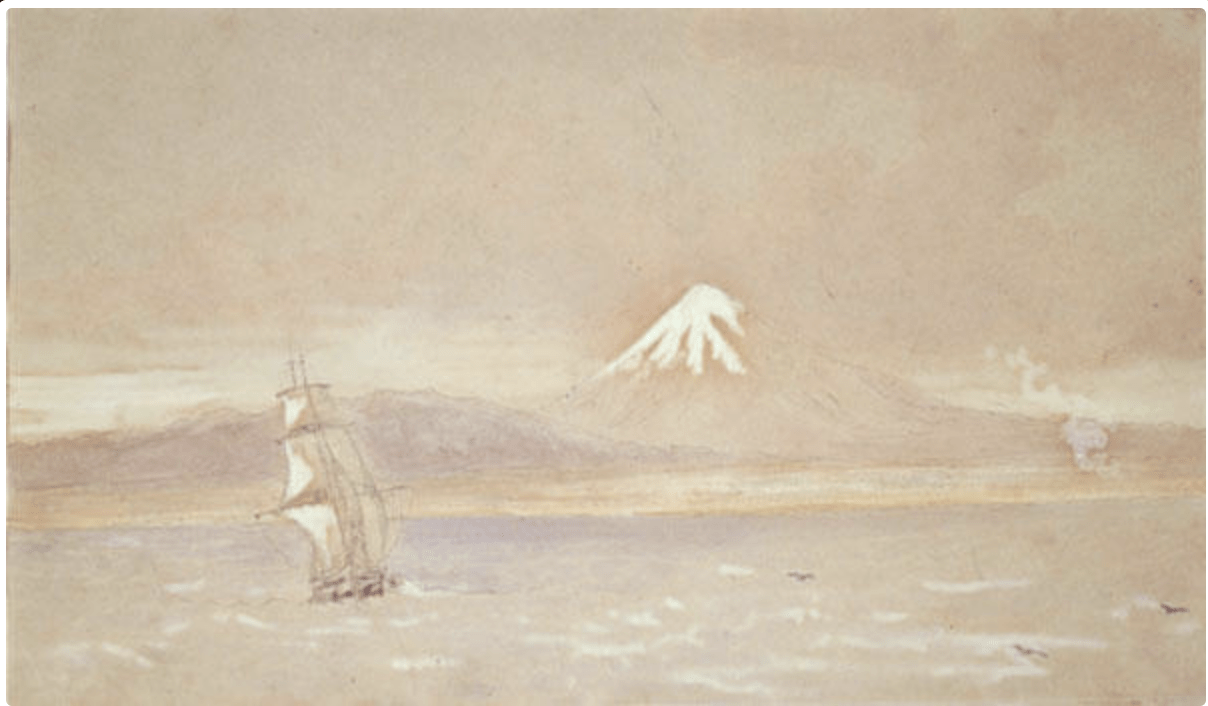

17th. (Lat. 40 degrees 27 minutes, long. 173 degrees 4 minutes.) A cry of “Land on the starboard bow” and a few raps at my cabin door with the mate’s heavy knuckles, soon awoke me from my dreams of home, and slipping on my trousers and great coat I hastened on deck. Daylight had just begun to dawn and a knobby outline of a grey colour was perceptible against the eastern sky. Nothing has ever given me so much pleasure as this sight of land; for excepting a distant view for a few minutes of the Is. of Brava, we had seen nothing but the broad ocean for four months. (Dr Henry Weekes, ‘VOYAGE IN THE BARQUE “WM. BRYAN” FROM PLYMOUTH TO NEW ZEALAND 1840-41,’ 35-36)

Further Reading

The unnamed daughter appears in two creative works associated with our project:

‘Sail Walk Drown’, a piece developed from the archival materials of the family letters that make up ‘the Family Songbook’, written and performed by Michele Leggott, Makyla Curtis, Betty Davis and Ruby Porter and directed by Makyla Curtis.

‘Emily and Her Sisters’, a poem by Michele Leggott published in Vanishing Points (AUP, 2017) and now also available on our website.

Sisters at a Glance: Navigation

#0 Introduction

#1 Emily Cumming Harris

#2 Catherine Harris

#3 Unnamed Daughter: Here

#4 Frances Emma Harris

#5 Mary Rendel Harris

#6 Augusta Harris

#7 Ellen Harris