By Dasha Zapisetskaya

Then as we neared our camping ground the branches of the trees were draped with greenish grey moss, which gave the forest a most weird appearance, as if the whole place had been dipped into the depths of the sea & had come up covered with seaweed. (Drawing Lines, 21 Jan 1890)

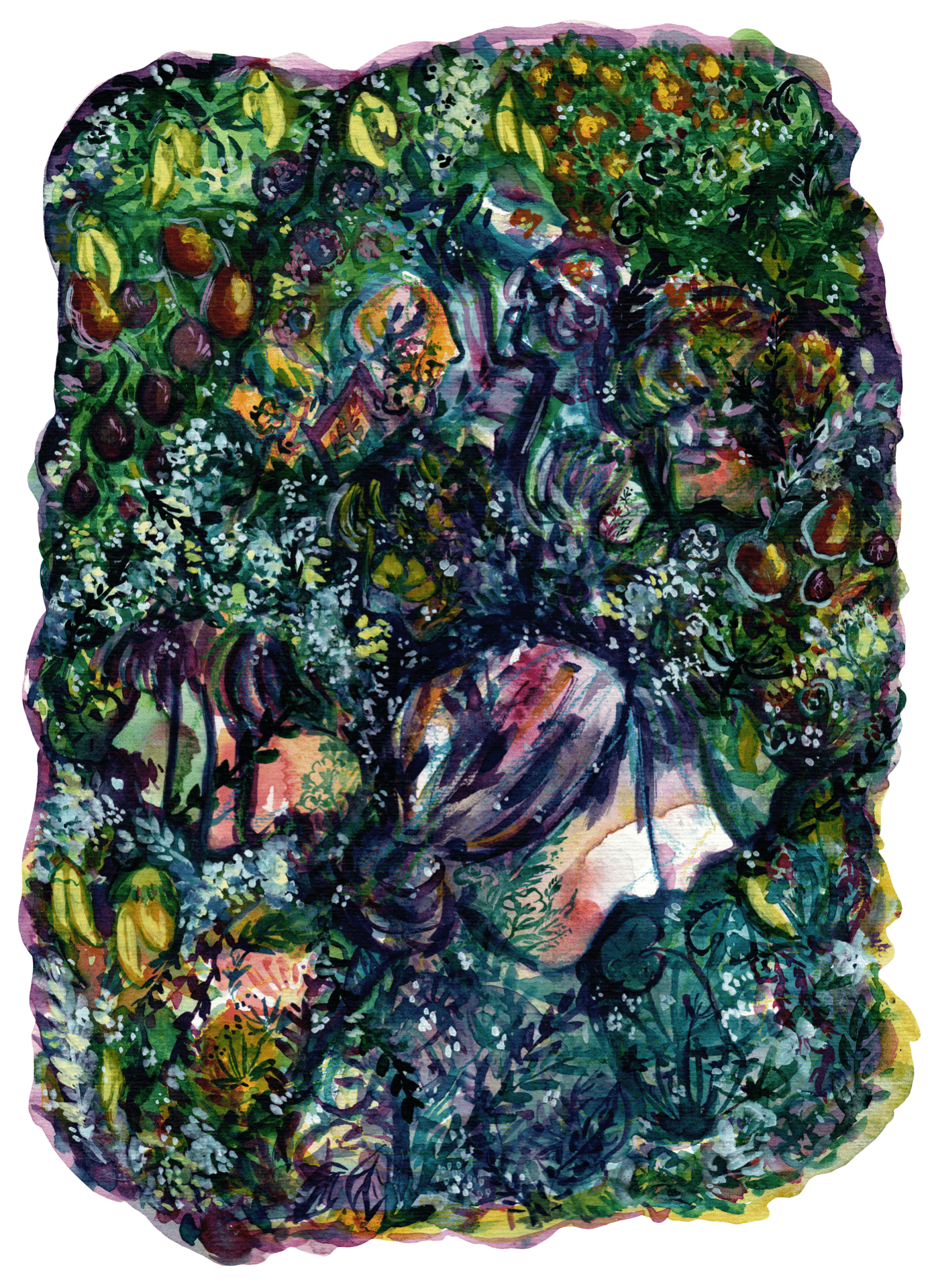

Emily Harris chronicles the natural world around her in a beautiful, atmospheric style, and this fanciful image of a forest dipped in seaweed, describing part of her trip through the Egmont ranges, is one I often return to. While reading Michele Leggott’s new poem ‘Dark Emily’, Michele’s ethereal natural images – “stems and leaves in your eyes… tendrils in mine” – made me think again of Emily’s fairytale forest.

“See how they got a T from the first initial… but see also how it could be a J” writes Michele, reminding me of the mystery of our research process, where one letter could alter the identity of a person in a photograph, which would in turn be the difference between the pieces of a story falling, or not falling, into place. Other sections such as “the copy of a copy,” “there can be two and one invisible… there can be two invisible,” and “this one is too young… this one was never there,” made me think again about the uncertainties of looking into the past, and I started to form a patchworked plan of the watercolour painting I wanted to do.

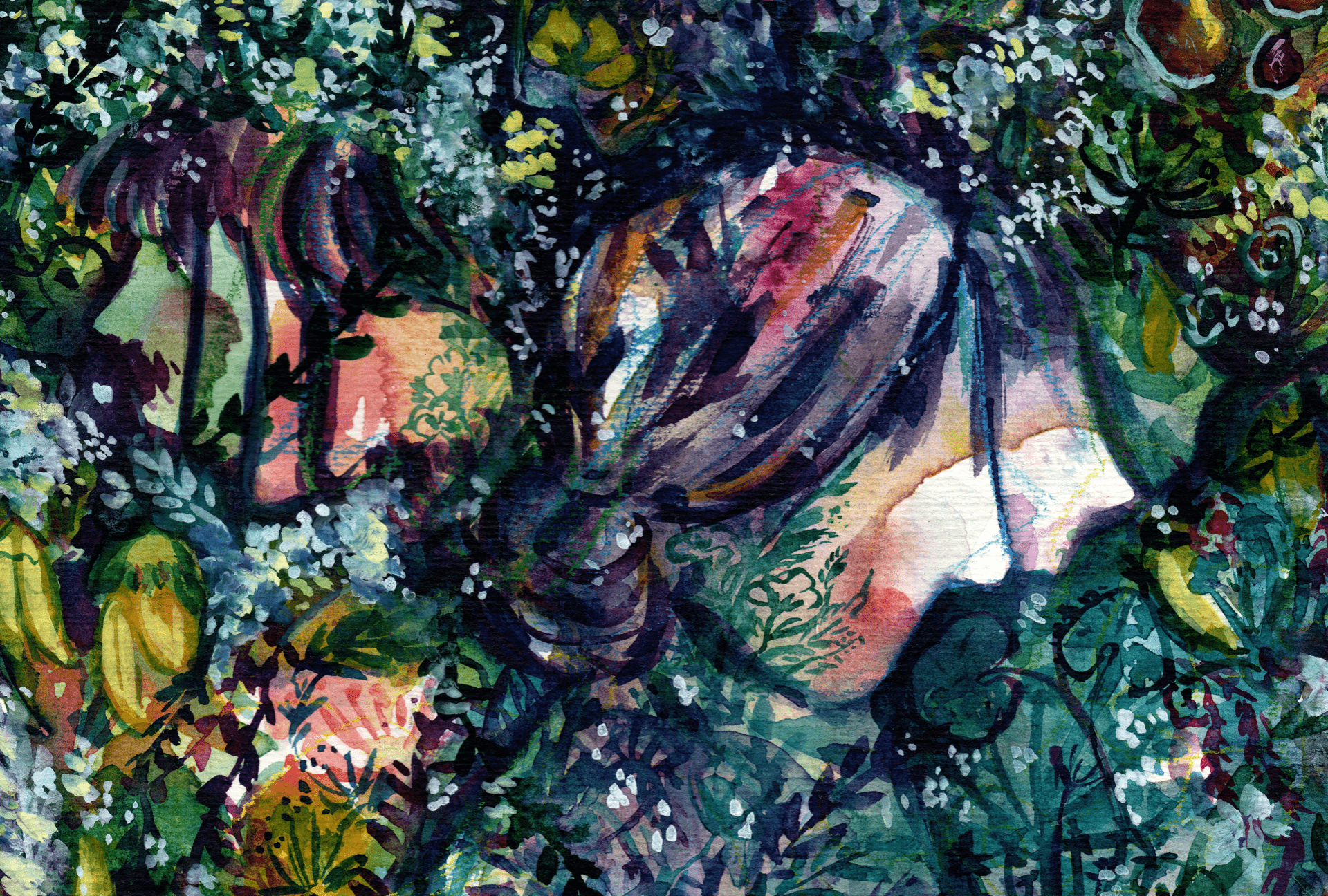

Using Michele’s line “I took my pencil and made marks” as a sort of general instruction, I took my paintbrush, turned on Michele’s audio recording of ‘Dark Emily’, and let the flow of the poem guide the composition. I didn’t make a pencil sketch, and only did one draft version before arriving at the final underpainting; while the completed work does feature many small details, I wanted to ensure that the beginning stage, which would decide the composition and overall atmosphere of the painting, was undefined and fluid. I used whatever colours felt ‘right’ as I listened to Michele read, choosing sea greens and blues (no doubt influenced by the seaweed forest), deep purples, and occasional spots of yellow and orange.

Emily’s own work is very precise and naturalistic, but I was not looking to recreate Emily’s style, nor to illustrate Michele’s poem in any literal way; I wanted to create a kaleidoscope of faces and foliage, memory and approximation, with the faces remaining anonymous and blending into the background, and the details swimming in and out of focus. To quote the line in ‘Dark Emily’ that became the painting’s central inspiration: a “spectral decoupage.”

My painting is populated with figures that could stand in for any of the people in the Emily story, representing the strange familiarity we feel for them after doing so much to uncover their past, combined with the detachment which is inevitable when trying to stitch history together. We might know some of the tale, but we can never recreate an exact picture of a person’s life, and every detail we uncover about Emily or her companions in electoral rolls or old newspapers is, at least at first, always them and not them at once.

Another element which is central to Michele’s poem is the relationship Emily had with her friend James Upfill Wilson, who is one of the most mysterious figures in the diaries and who lost contact with Emily before being admitted to an asylum where he passed away (‘James Upfill Wilson’, April 2020). We know little of the circumstances of their relationship or parting, but Emily clearly felt deeply sad about how things turned out: “poor James. Alas, life has much sorrow,” she writes (Drawing Lines, 17 Oct 1886). This sense of loss and lingering connection within disconnection, so central to Michele’s poem, is something I wanted to incorporate into my painting as well.

Alongside the smaller faces in the background, the piece has a central female figure to represent Emily. Thinking of James, I added a man behind her, facing away; connected and disconnected. “The world is wide | could be // and he is in it somewhere | couldn’t be.”

To create a “copy of a copy,” I added loose, receding outlines of Emily and James’ faces. Emily has two, in homage to the two sisters, Frances and Ellen, who feature so centrally in her diaries. The painting itself prescribes no fixed identities to any of the figures, and while ideas and memories of these people all influenced my process, the ultimate intention was to represent the feeling of a story only partly told.

Lastly, for reference and inspiration, I looked at Emily’s illustrations in New Zealand Flowers, Berries and Ferns as I painted. Among other plants, you might be able to spot the yellow Kowhai, purple Puriri berries, or rounded leaves of the kidney fern, all of which I got from Emily’s paintings and incorporated into the abstract, fragmented style of my own.

Starting off with painting alongside Michele’s poem and finishing with final touches in gouache to the flowers I plucked from Emily’s books, this painting helped me become further immersed in Emily’s world and reflect on how far our research team has come in reproducing her story. As with much of history, parts of Emily’s life and work will remain an approximation or an outright mystery, but it’s fun to get to know these spectral figures all the same.

Lead writer: Dasha Zapisetskaya