By Michele Leggott

With many research materials uploaded to the website 2019-21, our thoughts are turning to plans for a book about Emily Harris and her world that might utilise some of these online resources. I would like to write a book about Emily that introduces her work to a general audience, rather as she herself wanted to show the botanical treasures of Aotearoa New Zealand to as wide an audience as possible. The aim of such a book would be to present Emily’s art and writing to contemporary readers with context-rich excursions into the stories of colonial hope and ruin that form the background to her work across the nineteenth century and into the early years of the twentieth. Such a book might also include a range of contemporary creative responses to Emily Harris’s work. At very least it would represent her art and writing as essential components of a practice that deserves attention outside of the archives and museums that currently house its material traces.

Here is one such plan, centred on the importance of family narratives and open to inclusion of artwork by Emily, Edwin and Frances Harris.

Groundwork: Emily Cumming Harris, Artist and Writer

A trans-genre project designed to restore the visibility of an important forebear for women who write, draw and paint in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Twelve panels, conceptualised as interlocking essays and visuals that will tell the story of Emily Harris and her family in Taranaki and Nelson 1841-1925. The effect might be of walking past room-sized canvases entertaining fire and sword, chaos and ruin, black ants and rats in a settler colonial dwelling that also houses redemptive memory and hope of a time to come.

Six creative works by New Zealand women addressing a particular work by Emily Harris. If her poems have disappeared, we may write to or around the poet herself. If her delicate renditions of native flora have been forgotten, we may bring them back. If her vibrant letters and diaries kickstart a reevaluation of the single woman artist and her struggle to earn a living, we may reach a hand across time and place to where she stands listening for news.

The Panels / Stories

#1 This is the story of the fine girl

Sarah Harris remembers a daughter born on the voyage to New Zealand and buried at sea five days later. The child has no name but remains in her mother’s memory for 30 years, written and re-written as an absent presence among six living daughters.

#2 This is the story of mapping and painting

Edwin Harris surveys the Paritutu line, Waiwhakaiho River and Mangorie Stream with a party from Ngāti Te Whiti. The lines going down on the map retrace in part an earlier survey of the rohe and extend south and west to cover land wanted by settlers anxious to increase their purchase on rural sections in the New Plymouth area. But what contexts can be spoken for the whenua by its guardians past and present?

#3 This is the story of aunt Emma

Emily Harris’s self-education in Taranaki and Hobart owes much to the long-distance tutelage of her aunt Emma Jane Hill. Miss Hill taught at a boarding school for girls in Cornwall and collected the family letters from New Zealand for 25 years, encouraging her nieces to practise their powers of style and expression when they wrote to her. Following in the family pattern, Emily and her sister Kate became teachers in their mother’s schools in the Hurdon district in the 1850s.

#4 This is the story of the lighted windows

Emily Harris writes an elegy for her brother Corbyn who was killed in ambush on the beach at Waitara in July 1860. Edwin Harris memorialises his son in a haunting optical amusement in which light shines from windows and doors in wartime New Plymouth, a view that includes St Mary’s and the churchyard where Corbyn lies buried.

#5 This is the story of Holbrook Place

What opportunities might a nursery governess and housekeeper have to learn drawing and painting? Emily Harris spent four years working for the wealthy Des Voeux family in Hobart, writing poems and letters and perhaps receiving her first formal art training.

#6 This is the story of 34 Nile St

When Emily returns to New Zealand in 1865, her family has resettled in Nelson. Edwin sketches, paints and teaches drawing at a local boys’ school. Emily and her sisters Frances and Ellen become artists and later teachers themselves in the school that ran for almost 20 years close to the family home in Nile St. To what extent may a Victorian papa recognise and support the ambition of talented daughters?

#7 This is the story of Frances Harris

Frances Emma Harris, who loves poetry as well as painting and music, makes an ascent of Mount Taranaki with a party of six. She is the only woman of the party to reach the summit. Her journal of the expedition traverses alpine and sub-alpine habitats and is illustrated by watercolour and ink sketches of the route.

# This is the story of the missing work

On her return from the Melbourne International Exhibition of 1880, Emily Harris begins painting native flora on satin screens, mantel drapes, fans and table tops in the fashion of the Arts and Crafts movement. These items sell well but not a single example survives to show what they looked like. Their ghostly presence haunts Emily’s diaries and joins the lacuna that is her poetry of the same era. Then there is James Upfill Wilson of Motueka, the memory of whom Emily carries for years beyond his early death in 1878.

#8 This is the story of New Zealand Flowers, Berries and Ferns

Emily’s decision to produce an affordable publication to introduce general readers to New Zealand native flora is recorded in her diary of 1888. The development of the project, its underwriting by Nelson bookseller HD Jackson and the production of the lithograph books in London comprise a running thread in the diary 1889-1890. A few years later Emily began hand-colouring and signing sets of Flowers, Berries and Ferns, painting 36 plates and three title pages each time.

#9 This is the story of New Zealand Mountain Flora

A camping trip to the lower slopes of Mount Taranaki draws Emily’s attention to the ephemeral beauty of alpine meadows and she begins working on a book of 30 watercolours. The project founders for lack of money to reproduce the paintings in colour and the artist’s book, with botanical notes and poems, is lost and found again in England before returning to New Zealand in 1970.

#10 This is the story of Harry Moore

Emily Harris’s nephew Harry Moore left Taranaki for New South Wales and did not return to live in New Zealand. Harry married and had six daughters, the eldest of whom, Dorothy, became a point of reference for family history and connection back to her New Zealand aunts and uncles. What happens to letters and art works when trans-Tasman dispersals enter the picture? Who keeps the record and how does it travel between generations?

#11 This is the story of 23 Fulford St

When Emily’s nieces Constance and Ruth Moore purchase their own house in New Plymouth, it becomes a home for women in the family made single by separation or widowhood. The house is also the location of family papers, mementos and paintings cleared from Nile St after Emily’s death in 1925.

#12 This is the story of the active verb

‘I am like the active verb to be and to do,’ Emily Harris tells her mother. ‘I am too necessary an appendage to be left out.’ She is commenting on being burdened with menial duties by her lady employer. But we might take the comment at face value and ask how the creativity and ambition of Emily Harris was almost lost and why it is important to recover the art and writing of female experience across the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. A set of 12 paintings commissioned for the 1906 New Zealand International Exhibition in Christchurch shows the scale and quality of Emily Harris’s work and may be read as a case study for recuperation and reconsideration.

The creative works may include:

- Michele Leggott. Poem ‘Dark Emily.’

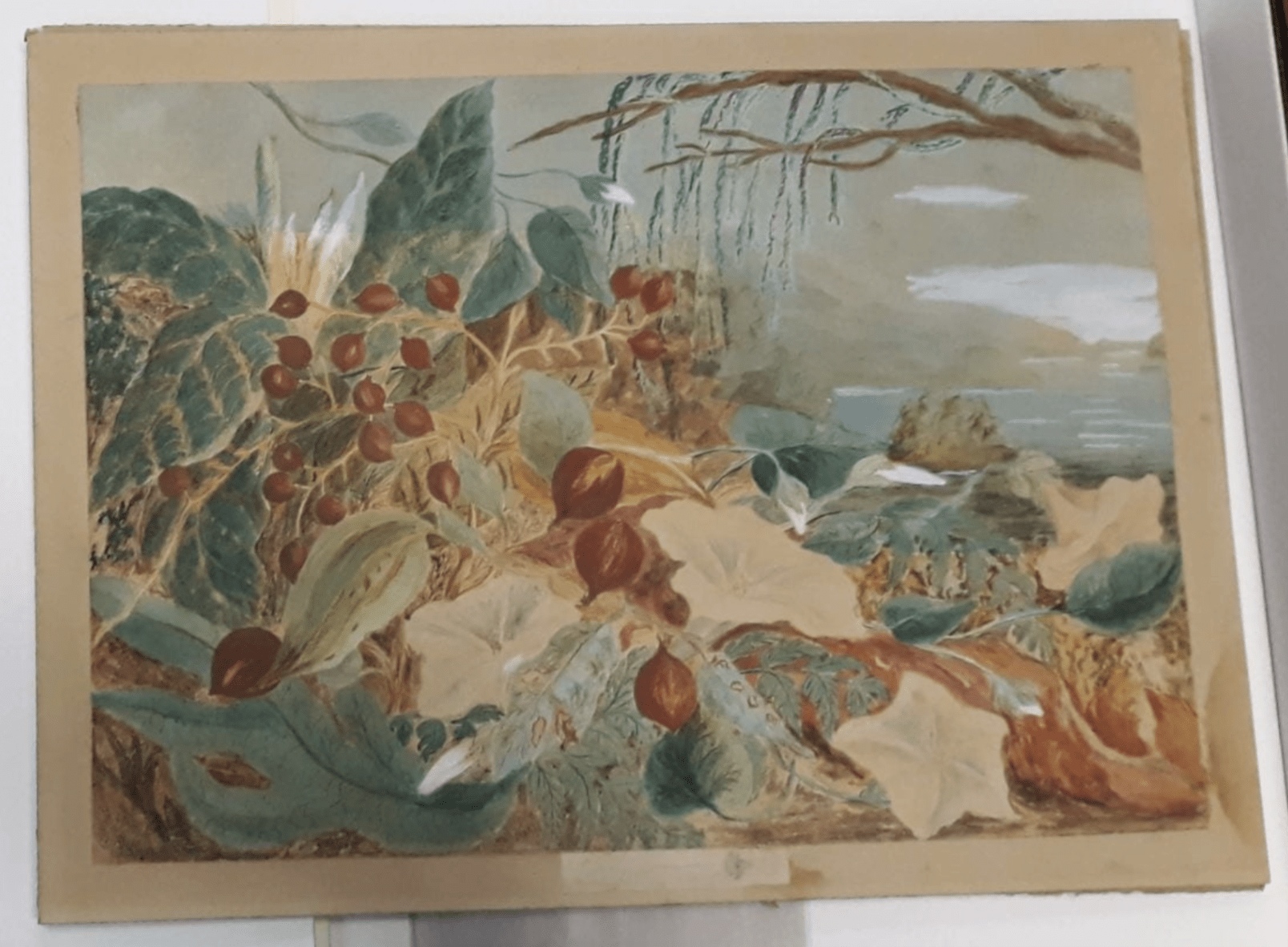

- Emily Harris painting: Titoki berries and white-flowering convolvulus). Undated. Watercolour, 250 x 350mm. Puke Ariki:

- Emily Cumming Harris, White-flowering manuka and pohutukawa. 1906. Oil on straw board, 810 x 520mm. Galpin collection:

Lead Writer: Michele Leggott