Miss Cottier: Independent Bookseller

By Kathryn Mercer

It is late 1888 and Emily Harris is beginning to look for agents who might sell her books of botanical drawings once they are published. In New Plymouth her sisters Kate Moore and Mary Weyergang explore then dismiss the possibility of either their husbands or sons being suitable agents. Reporting back to Emily in a letter, Mary suggests that “it will be best to try the booksellers, either Miss Cottier or Gilmour, your name will be quite sufficient in this place I am sure”.

Reading this in 2020, my interest was piqued: MISS Cottier? When I studied book history I understood that the few women involved in book trade before the twentieth century tended to be widows who were continuing their husband’s business. Yet here was a single woman running a bookshop, and being independently endorsed to an author in need of someone to help sell her work.

So who was Miss Cottier, and how did the Harris sisters know her?

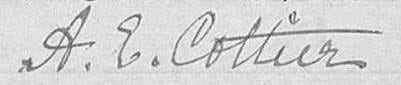

My initial hunch was that Miss Cottier was perhaps a very young woman yet to be married off. But no, Ann Eliza Cottier (1838-1914) was already an established spinster by the time she arrived in New Plymouth in 1874, aged thirty-five – well after Emily had moved away.

Born in Baltimore in the United States, Miss Cottier was the second-eldest in her family and spent most of her childhood on the Isle of Man where her father, James Cottier, and the rest of the children were born. He was a stonemason, said to be employing four men plus two household servants. In 1852 her father migrated to the Southern Hemisphere, leaving his wife and some of the children behind. Where Miss Cottier, then aged about 14, lived between then and her independent travel from Liverpool to New Plymouth via Melbourne I am still itching to uncover.

What we do know is that her mother died in 1863 and by the time Miss Cottier left England most of her siblings had also died. Her remaining siblings in England were now adults and independent – Thomas was working as a printer and Margaret had married two years before. Their father and another brother, William, had moved on from Australia to New Plymouth, where Miss Cottier joined them.

Ann Eliza Cottier was one of some 38,000 immigrants to New Zealand in 1874 – an annual net migration figure not surpassed until 2002. Unlike forty percent of the new migrants, Miss Cottier settled.

But why were they migrating? The New Zealand wars had damaged the country’s international reputation. Moreover, W.H. Skinner, an early New Plymouth historian, says there were no rich people left in Taranaki after the first Taranaki war. This economic hardship bled into the national ‘long depression’ from 1870 to the mid-1890s.

Part of Colonial Treasurer Julius Vogel’s solution sounds familiar today: try to stimulate an economic boom by borrowing overseas funds to pay for major infrastructure projects that create employment. Vogel also borrowed to fund mass immigration and to open up new land for the settlers. United Kingdom migrants were particularly favoured, with travel to New Zealand initially subsidised at just £5 per adult. In 1873 (the year Miss Cottier set off) the government went even further, offering free travel.

Existing New Zealand residents could nominate friends and relatives to join them: perhaps her brother William and her father James were influential. Advertising campaigns in the United Kingdom specifically called for single women of good character to work as domestic servants. It is perhaps understandable then that Miss Cottier’s first iteration of her business in New Plymouth in 1875 was the establishment of a Registry Office for Servants. This enterprise also marked the start of a long-term advertising relationship with the Taranaki Herald newspaper.

Spinster businesswoman she may have been, but this did not stop her entering and winning the girls running race as part of the festivities when the Governor came to inspect the local military Volunteers that year. The same year, the New Plymouth to Waitara railway line opened – one of Vogel’s infrastructure projects.

The availability of new books to New Zealanders had increased rapidly from the 1840s, and school attendance for Pākehā children was made compulsory in 1877, potentially increasing the literate population and therefore booksellers’ future markets. However, even by 1890 (when Emily was trying to get her botanical series published and distributed) twenty percent of New Zealand’s population lived in only four major centres. Outside of these, the small towns did not have enough turnover to support businesses devoted purely to books, magazines and circulating libraries; most bookselling was an aspect of a broader kind of business.

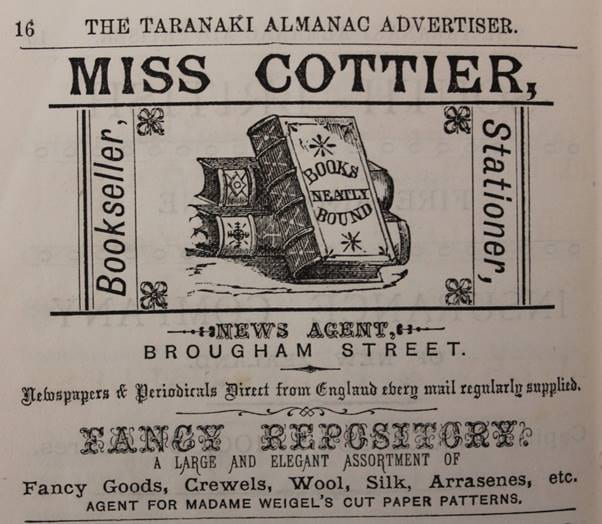

So, for example, Emily knew her Nelson publisher, H.D. Jackson, not only as a bookseller and stationer, but as a fancy goods importer, where she shopped for wool. Miss Cottier’s establishment developed along similar lines. By 1876 she was starting to diversify her business, arranging a London agent to supply a large quantity of the most recent English newspapers – available in New Plymouth two to three months after publication.

Another year on and we have the first evidence of her business diversifying further into books. The Taranaki Herald reports being given a pamphlet, The Policy of the Future, not Class against Class, by Sir George Grey. At the end of their review, the writer notes that, “The pamphlets may be obtained from Miss Cottier and as we presume Sir George Grey considers that anything paid for will be more highly valued than if given away, he charges the modest sum of one penny for the publication” (14 Nov 1877: 2). It would appear that Miss Cottier was business savvy enough to give selected materials to the local media for review, a practice she was to continue – thankfully for researchers!

By 1878 she was advertising as an agent for servants, a bookshop, stationer and ‘fancy repository’, not to mention being an agent for Tucker’s Tongue Sweepers produced by a chemist in Waitara. Another side-line Miss Cottier dabbled in over the years was taking orders for various merchants, the unlikeliest being R. Levett’s headstones and other monumental work; samples were on display across the road between the Town Hall and the Masonic Hotel.

Unfortunately, before Vogel’s plan of a sustainable boom gained a firm hold, further overseas borrowing was cut by an international financial crisis triggered by the October 1878 collapse of the City Bank of Glasgow.

In 1879 the New Plymouth Mechanics Institute, which incorporated a library, had fallen into debt and shut down. Shortly afterwards the secretary of the Institute’s Book Committee announced the formation of the New Plymouth Book Club funded by subscriptions out of Miss Cottier’s premises, describing her as the Club’s librarian.

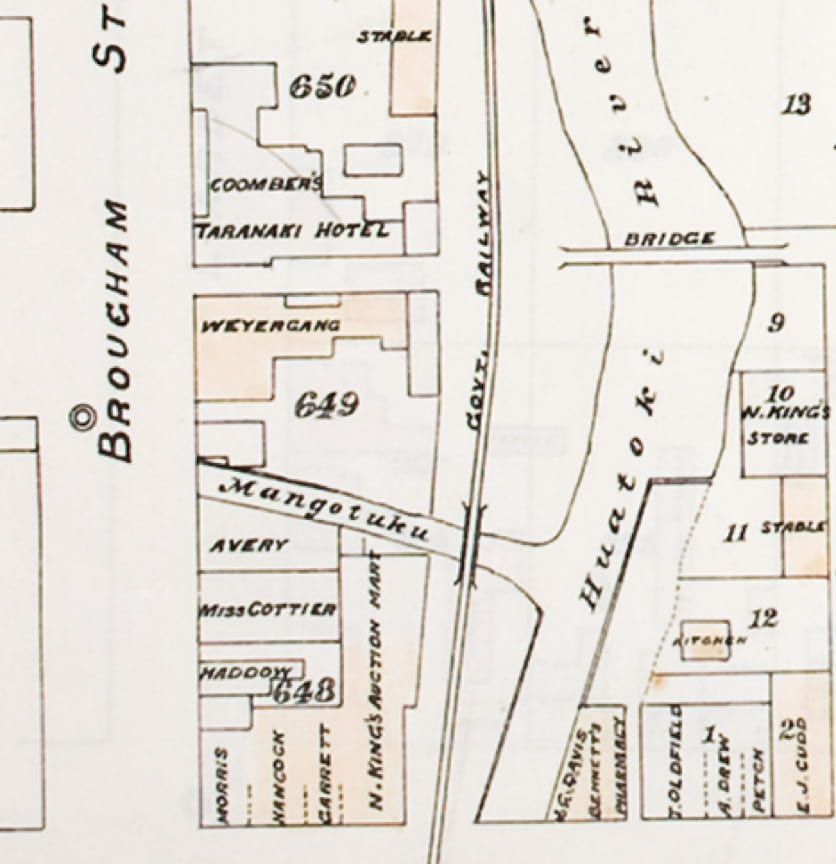

The Institute had occupied the ground floor of the Borough Council Town Hall in Brougham Street, and when the Institute shut down, the Council retained the reading room with a meagre collection of rather disorganised books with an untrained librarian who doubled as the registrar of dogs. Frustratingly for researchers, the reading room and Miss Cottier’s library were often referred to using the same names (yes, plural for both). Furthermore, Miss Cottier was known by several names (Ann, Annie, Eliza and Elizabeth), and so was the name of her shop as its emphasis moved with the times.

By early 1880 Miss Cottier had moved her business to Brougham Street, placing her right in the middle of the central business district just across the road from the Council building and its reading room. The same month Miss Cottier was in the news for taking in a Catholic woman: Mary Newbald was in court seeking a protection order after repeated domestic violence.

By August 1884 Mrs Alice Townsend had given up her neighbouring tobacconist shop in order to open the Clarendon House Temperance Hotel. The same month an editorial in the Taranaki Herald put in a plea for a free public library:

It is true there is a Book Club in the place, but the subscription to it is beyond the means of many, and consequently is not of that general character to be called a public benefit. Practically, therefore, the young men of New Plymouth [apparently the editor thought the young women didn’t matter?] who may be imbued with a taste for reading must either content themselves with cheap novels of a third-rate kind or incur the cost of buying expensive books for their own use. Owing to the difficulties there exist in the place for young men to improve themselves, they resort to frivolous or questionable amusements. Night after night they may be seen loitering or lounging about the streets as if life were given to them for no purpose but to waste it. (Taranaki Herald 18 Aug 1884: 2)

The idea dragged on, with a fundraiser in 1886 eliciting a letter to the editor by Mr A.C. Fookes, who ran the business on the other side of Miss Cottier’s shop:

The establishment and maintenance of a library in this town of a good library free of access to all classes is a matter of the greatest importance, and a benefit directly or indirectly to every man, woman and child in the place; but strange to say, even this profit is, it seems to have its [unnamed but female] opponents. (Taranaki Herald 19 Nov 1886: 2)

In June 1881 the Taranaki Herald reported that the Taranaki Book Club had received “an admirable selection [of books], including most of the latest novels’ from Mudie’s Library (15 June 1881: 2). As the Taranaki Herald explained, “Mudie’s library … is one of the largest circulating libraries in London” (6 September 1882: 2). By 1890 it had some 25,000 subscribers. Charles Edward Mudie’s influence on the publishing trade and in promoting Victorian culture and standards was massive – having a novel listed in Mudie’s catalogue was the best advertisement a commercially minded publisher could hope for. In his 1860 catalogue he states:

This Library is designed to promote the circulation of the best New Works in every department of Literature. The present rate of increase exceeds One Hundred and Twenty Thousand Volumes per Annum of Works of History, Biography, Religion, Philosophy, Travel and the Higher Class of Fiction.

Cheap reprints, Serials, Costly Books of Plates, Works of merely Professional or Local Interest, and Novels of objectionable character or inferior ability, are almost invariably excluded.

In September Newton King, a neighbouring auctioneer, sold without reserve the Book Club’s old collection of books pre-the Mudie shipment. This “large quantity of books” “sold remarkably well” (Taranaki Herald, 2 Sept 1881: 2 and 10 Sept 1881: 2). Periodic auctions of the club’s ‘old’ books continued through the life of the club.

Between receiving Mudie’s books and auctioning the old ones, Miss Cottier’s father ‘expired’. They had been living together for several years. The report on his death in the Wanganui Herald was preceded by a report on Māori again obstructing the building of the road close to Parihaka, “because the Government are encroaching upon their land, and they will not suffer it.” (Remember Vogel’s plan to open up new areas for settlement?)

Another milestone for Miss Cottier in 1881 was becoming the sole agent for Madame Weigel’s Paper Patterns and Weigel’s Journal of Fashion. Paper dressmaking patterns were already very popular in the United States when Johanna Weigel went on her honeymoon to Australia where paper patterns were largely unheard of. After having her style admired, the couple decided to settle and started the business in 1878, importing specialist tissue printing equipment. The business continued uninterrupted for 90 years, and the patterns are still considered collectable today. The monthly journal started in the 1880s, and “claimed to be the first fashion magazine to be designed, published and printed in Australia. It included illustrated fashion articles, housekeeping hints and serialized fiction.” Described in The Australian Dictionary of Biography as “the woman who clothed the Australasian colonies”, Weigel was extremely influential, particularly in rural areas, and quickly developed a network of agencies throughout Australia and New Zealand, including Miss Cottier. Stocking the fashion journals would have proven helpful for informing Miss Cottier’s selection of haberdashery and fancy goods in her shop.

By the time Emily was trying to publish her books, the Taranaki Almanac for 1888 not only ran an advertisement for Miss Cottier’s bookshop (see the top illustration), but also listed under libraries both the Public Reading Room in the Town Hall Building (with Mr A. C. Fookes listed on the committee) and Miss Cottier’s Book Club and Subscription Library.

While we have no evidence that she ever stocked Emily Harris’s books, we do know that Miss Cottier stocked other New Zealand publications, so it isn’t inconceivable that she sold New Zealand Flowers, New Zealand Berries and New Zealand Ferns.

Miss Cottier attended the Anglican Church, St Mary’s, as did Kate Moore and Mary Weyergang and their families, so the three women must have had at least a nodding acquaintance. Miss Cottier’s approach to life was non-denominational, which can’t have hurt her business but may not have been helpful for her relationship with her brother William. Even as Miss Cottier sold tickets for various churches’ fundraisers, her publican brother sold tickets for a racing sweepstake. The newspaper records Miss Cottier assisting with serving tea at the Boxing Day Temperance Picnic which was attended by at least 1500 people – did William see this behaviour as disloyal? Without access to letters or diaries the Cottiers may have written, we can only guess.

By the turn of the century, Sir Walter Buller in reference to Māori is said to have suggested that the role of Pākehā was to “smooth the pillow of a dying race”. But for Pākehā New Zealand’s economic situation had finally turned around and the country was prospering with refrigerated ships exporting meat and butter from the expanding dairy industry.

In 1901, the British and Foreign Bible Society established a depot in Miss Cottier’s shop. She acted as agent, selling Christian scriptures not only in English, but Māori, French and German with a selection of forty-five different kinds of type and binding. The following year the Society reported no profit, the collection was reorganised and put in a larger case, and the Bibles were sold at the same price as they could be bought in London, “this is a considerable reduction on the price of any other Bibles published.” By the 1904 AGM, the society was well in the black, and they decided to increase the volume of books available through the depot at Miss Cottier’s. Furthermore, “the needs of the Chinese of the district were discussed, and a supply of Chinese testaments is to be obtained for distribution.” (Taranaki Daily News, 9 June 1904: 2). They reported having sold 164 volumes in 1906, with 309 volumes in stock in 1907. Reverend Osborne “remarked on the very efficient and painstaking conduct of the depot, and the care of the stock by Miss Cottier” This was the last year Miss Cottier advertised the depot in association with her shop (Taranaki Daily News, 7 Feb 1907: 2).

Throughout the duration of her business, Miss Cottier also regularly donated books for school prize givings and to worthy organisations such as the New Plymouth Hospital, and for many years she coordinated an annual collection for Dr Barnardo’s English orphanages – all of which was helpfully reported by the local newspaper, which she also sold.

The last year the Book Club was mentioned in the local newspaper was 1888. She still described herself as a bookseller until at least 1893. While I could find no evidence of Miss Cottier signing the Suffrage petitions of 1892 and 3, or of her voting in the 1893 elections, she did appear on the electoral roll for 1896.

Miss Cottier’s Magazine Club ran until at least 1902. In 1904 a new circulating library and magazine club was announced in town run by T. R. Hodder. For Miss Cottier, fancy goods, toys and novelties gradually squeezed out the mention of publications in her advertisements. Eventually she was simply described as a storekeeper.

In July 1908, the New Plymouth Carnegie Free Library was finally opened. In 1909 Miss Cottier made her will, and in June announced in the paper “to her old friends and numerous customers that she has disposed of her business,” which was renamed (again) The Fancy Depot under the management of a Miss Weller – with no reference to bookselling at all (Taranaki Herald, 4 June 1909: 3). Miss Cottier had just turned seventy-one years old and had run her business in New Plymouth for thirty-five years.

When her father died in 1881, she was left with two brothers, the hotelier William and Thomas the printing compositor in Lancashire, plus her youngest sister, Margaret (by then known by the more exotic name ‘Margaretta’) Cooley. By 1884 Margaretta and her husband had migrated to Baltimore. By 1905 William too was dead.

Just weeks after her retirement Miss Cottier was off to visit her sister in Baltimore in the United States, a journey that was to go via Fiji to connect with a vessel going to Vancouver. Her intention was to follow up the visit with a detour to England.

Perhaps ironically, just after Miss Cottier left there was a complaint about the Public Library in the Taranaki Herald, saying that it charged subscription fees, was poorly used and held a lot of ‘trashy’ material.

While she was overseas, Margaretta’s husband died: had Miss Cottier known he was ill before she departed? By the time of the US Census in April 1910, the widow Margaretta was in rental accommodation with her two unmarried children: Constance, aged 37 was a trained nurse, and Albert, at 36 years old working as a bookkeeper. Miss Cottier was not recorded. However, a personal advertisement some months later says she left Baltimore on the 6 October 1910 after residing with her sister for about a year. By December she was back spending a little time in Auckland.

On her return to New Plymouth, “she settled down to enjoy her retirement,” (Taranaki Daily News, 24 Mar 1914: 5), continuing to organise sending funds to Dr Barnardo’s Homes for orphans. There was the occasional mention of her in the ladies pages – attending a church social wearing black silk to farewell the Skinner family, and at the opening of the New Plymouth Bowling Club’s green, “wearing a navy coat and skirt [with a] putty coloured hat relieved by magenta velvet” (Taranaki Daily News, 11 Nov 1911: 6). These descriptions of her outfits are as close to an image of her as I have found.

After a short illness in 1914, Miss Cottier died. Her entire estate, estimated as being worth less than £450 (equal to approximately NZ$70,000 in 2019) was left to her “dear sister” in Baltimore, “for her sole and separate use”. Should Margaretta have already died, Miss Cottier’s will was most specific that the estate would then go to Constance. There was no mention of Albert, nor her brother Thomas (although perhaps he was already dead), nor of any of her nieces or nephews descended from William in Taranaki.

The Taranaki Herald paper honoured her with a small obituary. Often obituaries (which were mostly for men at that time) would use terms like ‘greatly respected’, ‘amiable’, and such. Miss Cottier, however, was simply described as “Another of New Plymouth’s old identities …. Who for many years carried on a fancy goods business” (Taranaki Daily News, 24 Mar 1914: 5). She was buried with her father James in the Te Henui cemetery.

Which brings us back to the question: how did the lives of Kate Moore, Mary Weyergang, Emily Harris and Ann Eliza Cottier intersect?

Emily visited New Plymouth the year before Mary’s 1888 letter, probably during her summer holidays, to paint and sketch and catch up with her Taranaki sisters and her 11 nieces and nephews. Frustratingly, her diary for 1887 is lost, so there is little detail about the visit. We do know that Emily would have stayed with one of her sisters (probably Mary) who lived close by each other on Devon St East. By this time the town was laid out with tidy footpaths complete with kerbstones. So while the sisters may have had to wait for a train to cross Devon Street, the walk into town was a ten minute stroll down the hill from Mary’s house (what is now 196 Devon Street East), to Miss Cottier’s shop on lower Brougham Street. The shop was sited roughly where the Bookstop Gallery is today (another bookshop selling a side-line or two).

Brougham Street was regarded as the centre of the town’s business area, forming the divide between Devon Street East and Devon Street West, so it is not unthinkable the ladies would visit there, perhaps stopping to buy some wool or fancy work supplies. A plan examined late in my research shows that this was also the street where Mary’s husband August Weyergang ran his business selling ironmongery with a side-line in liquor, just three doors down from Miss Cottier, bookseller, renowned for her enticing window displays.

Guest contributor: Kathryn Mercer, Information Services Officer | Kaiawhina Ratonga Rangahau

Taranaki Research Centre | Te Pua Wānanga o Taranaki