‘Emily Harris in Full Bloom’

By Catherine Field-Dodgson

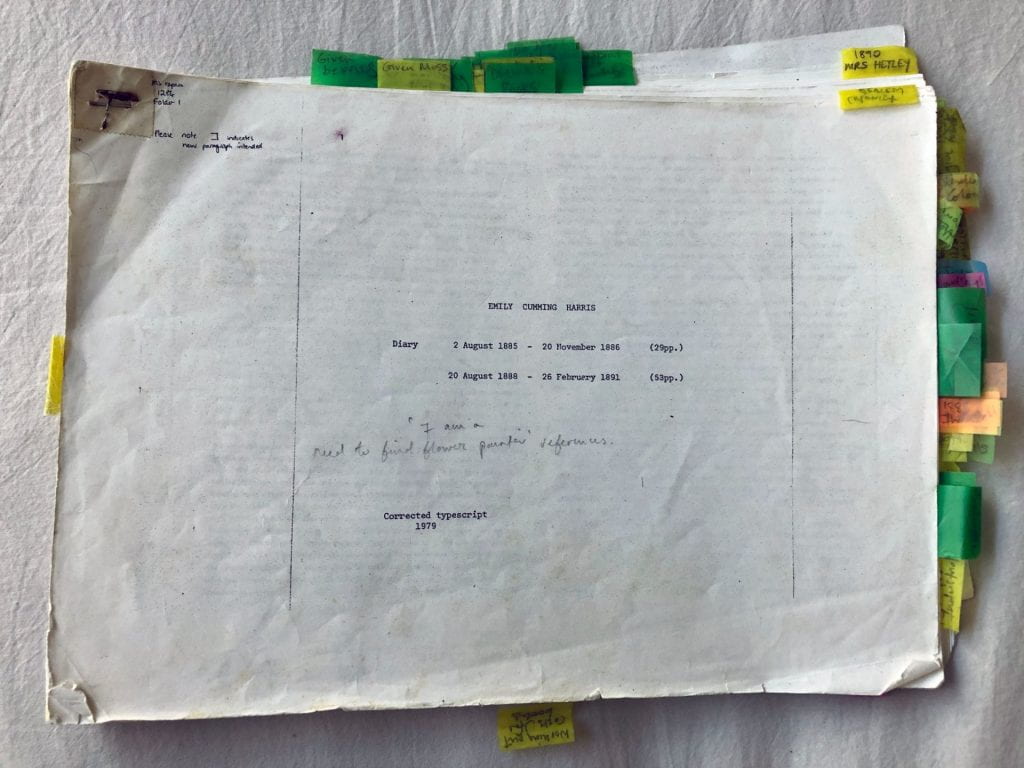

When I was working on my 2003 thesis ‘In Full Bloom: Botanical Art and Flower Painting by Women in 1880s New Zealand’, Emily Harris quickly became my favourite botanical/flower painter to research. Of all of the notes and research material I compiled 18-odd years ago, the only item I’ve kept is the transcript copy of Emily’s diary – well worn and covered in post-it notes! Like many others who read her diary, I was able to get a real sense of Emily’s personality as she recorded her personal hardships, domestic chores and her determination to be taken seriously as an artist. But my favourite parts of her diary are the entries where she describes the natural world around her – she had such a keen eye and obvious passion for Aotearoa’s natural history. Emily writes about her fern-gathering expeditions, and how visitors brought her sprigs of blossom, orchids, nīkau berries and baskets of moss to draw and paint. She records a trip to the Nelson Port Hills to watch an eclipse of the sun, and mentions that people heard the Mount Tarawera eruption in Nelson. One of my favourite paintings of Emily’s is an oil painting in the Nelson Provincial Museum, of a white comet’s tail streaking against a dark night sky (possibly the double-tailed comet ‘Viscara’ in 1901).

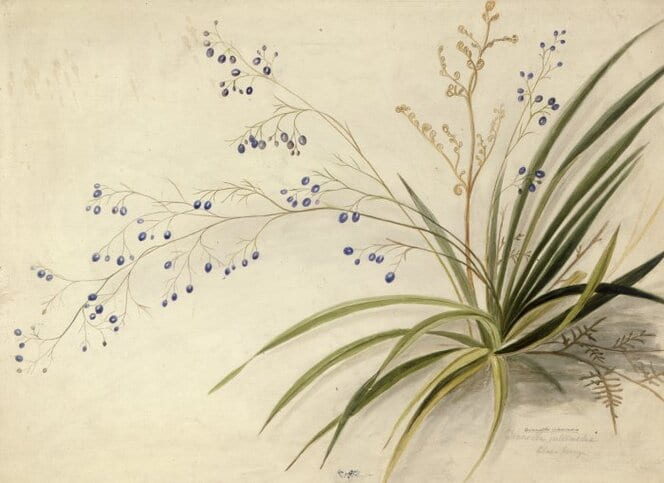

Another of my favourite works of Emily’s is her watercolour painting Dianella intermedia (Blue berry) (1890s? C-024-011, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington). I remember thinking ‘how stunning’ when I first laid eyes on it. Dianella/Tūrutu is a loose tussock native plant with long green leaves, that produces blue berries at the end of summer. Emily renders the little berries and their delicate stalks so beautifully in her watercolour. I’d never heard of this plant prior to seeing Emily’s painting, and now they’re my favourite plant to spot while out walking in the bush and I’ve planted several in my garden.

I was incredibly fortunate to have Roger Blackley as my thesis supervisor at Victoria University of Wellington, and was one of his first MA students. He possessed an absolute wealth of knowledge about colonial New Zealand. Roger had copies of many of the colonial exhibition catalogues in his office, and would point me in certain directions to go researching. I spent many happy hours in the dimly-lit basement of the National Library looking at newspapers on microfiche, ‘treasure hunting’ for advertisements and exhibition reviews, in the pre-Papers Past era.

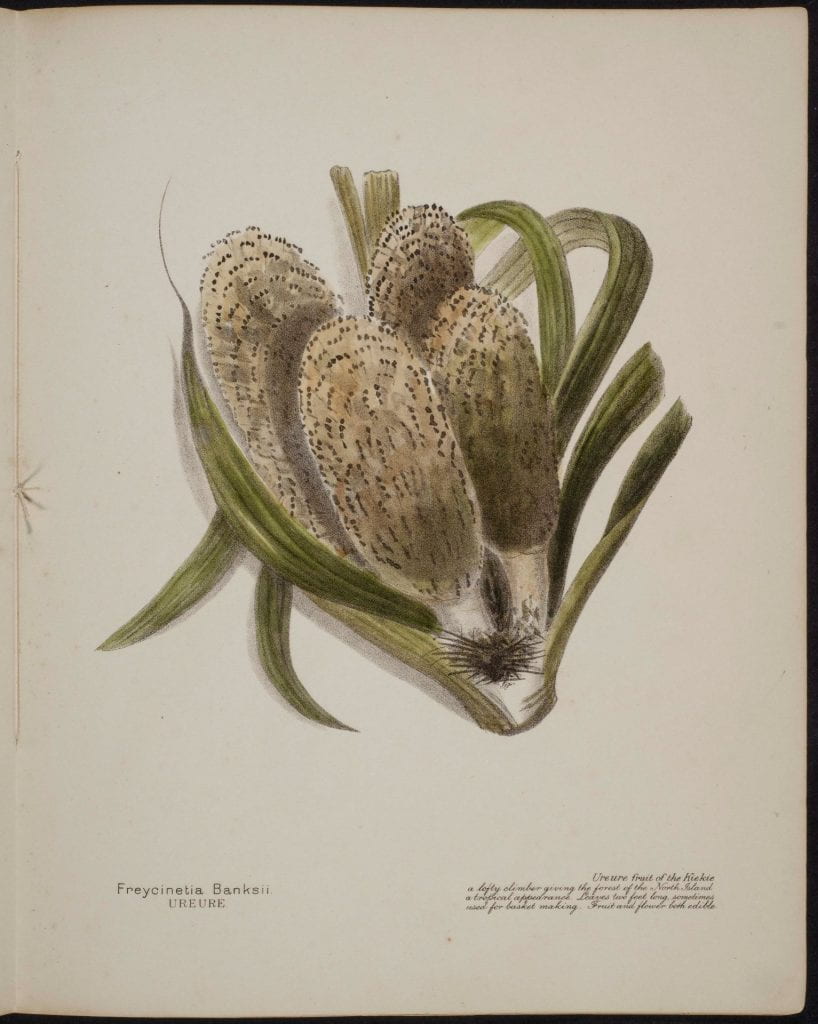

Roger and I used to speculate about what might have happened to Emily’s artworks, particularly her decorative art objects, such as her painted screens and table-tops. What happened to the lithographic stones her books were printed on in London? (We guessed they were probably cleaned and re-used). When I was looking at one of Emily’s works Freycinetia banksii (Ureure), Roger delighted in telling me what the word ‘ure’ meant in Te Reo Māori, and cackled as he said he’d also once mentioned this to a group of elderly Pākehā women in an art gallery.

Part-way through my research phase, Roger met a couple at an art function and discovered they had one of Emily’s books in their possession. They kindly invited us to their house in Kelburn for afternoon tea, where we ate fruitcake and had a chat about Emily and her works, and they provided me with a rare opportunity to see one of her uncoloured book editions in a private collection. Roger sadly died last year, and I know he would have loved this project and been fascinated to learn about all the different collections around the world that house Emily’s artworks and books.

Roger taught me research skills that have been invaluable for unpacking several family history mysteries in my own whānau, and recently we have re-established links with our Rongowhakaata iwi in Tairāwhiti/Gisborne. Roger’s book Galleries of Maoriland (Auckland University Press, 2018) and my research into my 2x great-grandmother, who – under duress – sold the land that the city of Gisborne was founded on, has recently got me re-thinking about Emily and her contemporaries: Emily was part of a Pākehā colonial community that ‘settled’, surveyed and cleared a landscape that was already inhabited. She occupied a critical moment in the history of Aotearoa, where the landscape literally and figuratively changed before her eyes. Hers is a history built on top of displacement and dispossession of tāngata whenua, the impact of which continues today, and it is important to acknowledge that.

I remain curious about Emily’s knowledge of Māori plant use and Rongoā Māori (traditional Māori medicine) practices, in relation to some of the plants she collected. She displayed an awareness of the useful properties of some of the plants, such as the berries of the Karaka:

‘Fruit bright orange colour, pulp edible, the kernel poisonous until steeped for a long time in salt and water, formerly much used for food by the Maories’ (Emily Cumming Harris, New Zealand berries, Nelson: H. D. Jackson, 1890, p. 4)

And the fern Marattia fraxinea in New Zealand ferns:

‘Edible fern. A very handsome plant growing inland in the North Island. It is prized for gardens and green houses. The root resembling a horse shoe, is baked and eaten by the Maories’ (Emily Cumming Harris, New Zealand ferns, Nelson: H. D. Jackson, 1890, p. 3)

This is another intersection that would be interesting to explore: where/how did Emily learn about these plant properties and their relationship to Māori? As noted in the present project’s description, these sorts of juxtapositions, intersections and examinations of a wider context offer “… a richer understanding of the conditions of time and place that ultimately connect with our decolonising but forgetful present.”

Catherine Field-Dodgson has a master’s degree in art history from Victoria University of Wellington, supervised by Roger Blackley. She’s previously worked as a press secretary and events organiser, and lives in Lower Hutt with her partner and their two children. Catherine is currently researching her 2x great-grandmother Keita Halbert/Wyllie/Gannon (Rongowhakaata).