The Erasure of Mrs Corrigan

By Dasha Zapisetskaya

Recounting the camping trip in late 1888 that has led us to so many interesting discoveries, Emily Harris lists her fellow campers travelling to the Wakapuaka district by coach, among whom are:

Married ladies: Mrs Wright, Mrs Corrigan, Mrs Washbourn. […]

Children: Julie, Winifred & Dorothy Wright, Trissie Corrigan. (9 Jan 1889)

As we had already started piecing together the identities of the other campers, it was now my job to find out more about Mrs Corrigan and Trissie, who we assumed was her daughter.

Emily is clear about Mrs Corrigan being married, so it was unusual to see no Mr Corrigan on the list. I thought perhaps we were looking at someone similar to the widowed Mrs Buckeridge.

My search uncovered two eligible Mrs Corrigans: Elizabeth Corrigan (née Seymour), and Deborah Corrigan (née Blake). Elizabeth’s husband, Hugh, died in 1873, and was buried in Wakapuaka Cemetery, Nelson. The Nelson Evening Mail and the Colonist published numerous reports of Elizabeth Corrigan’s bankruptcy in 1883 and, keeping Trissie in mind, we noted that she had three daughters. Elizabeth had a strong link to Nelson and her family mapped on to the limited clues obtained from Emily’s diary.

Deborah Corrigan had an even more unusual story. She and Hugh are the only two Corrigans buried in Nelson, although they are not in the same plot and marriage records show that they were not husband and wife. Deborah married Cornelius Fookes Corrigan in 1874 and, while with many archival couples there is little else we can find about the course of their marriage, there is much more to the story of this one.

Many results show up on Papers Past for the name Cornelius F. Corrigan. In 1879, the Hawke’s Bay Herald reported Cornelius’ bankruptcy:

Notice is hereby given that the above named Cornelius Fookes Corrigan hath this day filed in this Court at Napier a Declaration of his inability to meet his engagements with his Creditors. (Hawke’s Bay Herald 5 Jun 1879: 3)

Some years later the Grey River Argus and the Press published reports of Cornelius’ conviction for forgery. The former reports on 22nd March, 1884, that he was ‘committed for trial on three separate charges of forging cheques on the Bank of New Zealand at Blenheim,’ and the latter reports on 17th April that the sentence was passed in the Supreme Court of Christchurch and Cornelius was given three years penal servitude for forgery.

In my research, whenever I find a man making the news – for things good or bad – I cannot help but think of his wife, the silent participant in every court case and news story at a time when women relied on their husbands and fathers for financial support. Between the reports of 1879 and 1884, Cornelius appears to have moved about from Hawke’s Bay to Marlborough and Canterbury (there were bad cheques passed in Kaikoura as well as Blenheim). The movement repeats an earlier pattern of newspaper reports in the mid-1870s, from locations as diverse as Balclutha, Whanganui and Kakaramea in southern Taranaki. Sometimes Cornelius is engaging in professional activities as an accountant, sharebroker or a stock and commission agent, sometimes he is being pursued by the law for infringements of trust. There is no sign of Deborah in any of these locations except for Balclutha, where the Corrigans were living in the early days of their marriage.

Cornelius and Deborah were married 17th January 1874, probably in or near Thames, where Deborah’s parents lived. The Corrigans’ first child, a son, was born in Balclutha in the third quarter of 1874, indicating that Deborah was probably pregnant when she married. Their second child, a daughter, was born 11th September 1875 in Mary St, Thames, the address of Deborah’s parents, Mr and Mrs Robert Blake. No further children of the marriage are recorded, and it is possible that the Corrigans were not living together after 1875.

We can see that the first years of the marriage included some lively social entertainments, a pattern that Deborah would continue in later years. In 1874 Mr and Mrs Corrigan are noted in Balclutha papers for their theatrical endeavours. They are musical, both singing several songs at the Grand Amateur Concert at Barr’s Hall, Balclutha, in December 1874, and appearing in the Church of England Concert earlier that year. The Clutha Leader describes Mrs Corrigan’s singing as having ‘exquisite taste and sweetness’ and amusingly reviews Mr Corrigan’s performance: for one song, although it is ‘one of that gentleman’s but perhaps not the public’s favorites’ he is given an encore for his ‘usual comic style.’ About another song, the paper notes that ‘he sang well, and would have done much better had he known the words.’

After Cornelius’ bankruptcy in 1879 and his conviction for forgery in 1884, the archival curtain drops and the Corrigans, particularly Deborah, proved difficult to find. However, in early 1883, I discovered not only Deborah but her quoted words. She was in Thames, testifying as a witness to an attempted sexual assault case brought by Mr and Mrs Ehrenfried. Deborah Corrigan is on the witness stand:

I reside at the Thames, next door to Mr Ehrenfried’s, and I am on visiting terms with them. On the evening of Thursday, the 23rd December, I was alone, mamma being ill in bed. At about nine o’clock, I heard distressing screams from Ehrenfried’s, in which the word “Help” was distinct. (Auckland Star 27 Jan 1883: 2)

The statement that she was ‘alone’ with ‘mamma being ill in bed’ sounds like one that could be made by a single woman still living with her mother. But things soon started to fall into place, and I realised that we had the right person. In Deborah and Cornelius’ marriage announcement, her father is named as Robert Blake, Esquire, of Thames. The death of ‘Robert Blake, the last lineal descendant of the famous Admiral Blake’ is announced in the Thames Advertiser in 1882, stating that he died ‘at his residence’ in Mary Street. Mr Louis Ehrenfried can be found in the area directory for Thames in 1878-1879 living in Mackay Street. After a quick look at Thames on Google Maps, I discovered that Mary Street and Mackay Street intersect, so the Ehrenfrieds and the Blakes were neighbours. Perhaps Deborah came to live in Thames to help ailing parents or because she had separated from Cornelius, but either way, we can say with certainty that Deborah Corrigan was not living with her husband in 1883. She continued her involvement with the theatre, however: the Thames Advertiser in 1881 declares that ‘Mrs Corrigan deserves much credit for her efforts’ in her performance as Maid Marian in the ‘Merrie Men of Sherwood Forest’ given by the choir of St George’s Church.

Is Deborah the Mrs Corrigan of Emily’s diary? She is buried in Nelson and her son, Dominic, is the only Corrigan registered in Nelson for 1896, living in Hardy Street. However, the other piece of the puzzle was always going to be Trissie Corrigan, listed by Emily under ‘Children’ and therefore a young girl at the time of the camping party. To return to Elizabeth Corrigan, our initial suspect, the only daughter she had likely to be considered a child in 1888 was Georgina, born in 1870 and about 18 at the time of Emily’s record. Fitting the nickname ‘Trissie’ and the label ‘child’ onto her seemed rather like putting a square peg in a round hole. Deborah, on the other hand, had only one daughter: Beatrice Alice Corrigan, who would have been 13 at the time of the camping out party. Here was our Trissie, and with her the correct Mrs Corrigan.

Because the research process has a mind of its own, this was not the end of the Corrigan saga. A few days later, when I was looking for something unrelated in our images of Emily’s handwritten diary, an interesting detail caught my eye. I was not up to this section of the source text in my transcription process, so I had not seen it before. It was a gap in the middle of a diary entry, where a name, following the word ‘Mrs,’ was scratched out and drawn over with a thin black line. The same thing appeared on two later pages – a name scratched or rubbed out, leaving a blank in the text. Transcribers Margaret Jeffery and Jeanine Graham, working on Emily’s diary before me in 1964 and 1979 respectively, had left the blank, not being able to make out the erased name. But I recognised it at first glance: Corrigan. I owe the discovery to the strange serendipity at play in the research process. If I had not spent some hours that same week looking for, typing out, and reading the name ‘Corrigan,’ I might have found this redaction as obscure as everyone else.

Emily’s censoring of Mrs Corrigan’s name looks and sounds odd: a textual rupture that reflects an emotional upheaval in the usually calm lives of the Harris sisters. The first time Mrs Corrigan’s name is scratched out is in the entry for 21st May, 1889. In January of that year, describing the camping trip, Emily writes about Mrs Corrigan quite openly; she recalls that ‘Mrs Corrigan, Nelly Rochford & Julie Wright went with me along the road to Cable Bay, & I did a little more to my sketches. In the afternoon three of us went to have a farewell bathe in our lovely river.’ From this description, they seem to be on very amicable terms. What changed?

Emily tells us:

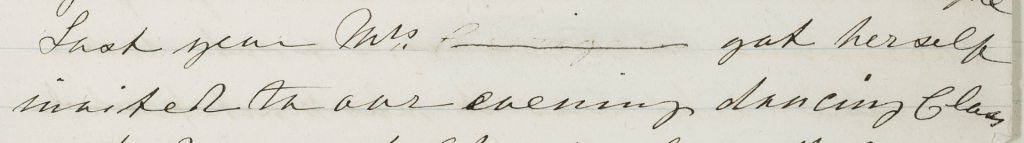

Last year Mrs [Corrigan] got herself invited to our evening dancing class. We had no children’s class that year. She got up a children’s class & rented our room. This year we supposed she would again have a children’s class. She one day asked Frances if she would join her in getting up a large children’s class, F. said she would think about it.

Some time after she met Frances & told her that she had been asked by six gentlemen to get up an evening class. She hoped she was not interfering with us, some of those who were coming to her she had not even heard of before. So we supposed she had got together enough to form a class without interfering with us. However we soon found that the case was very different, she had invited all the girls who came to our class, & asked every one of our gentlemen to join & every youth who might have joined our class, and a sufficient number of those who would have come to [us] have joined her class, to make it quite impossible for us to have a class this year.

She knew this quite well & she also knew how much my sisters depended upon getting up their class. Many of the ladies she invited would not go, but others thinking we were not going to have one this year saw no reason why they should refuse. (21 May 1889)

A difficult situation indeed. Emily routinely mentions in her diary that she and her sisters struggle to get enough students for their children’s school and for the lessons in painting, music and dancing they offer adult learners. Her angry response to Mrs Corrigan’s behaviour is understandable. The diary continues:

She began at getting her class together very early in the season allowing people to suppose that we were not going to have one. She sent Frances a card of invitation for the first evening but Ellen & I were left out in the cold. Only to invite one after having enjoyed herself a whole season at our house. Ellen will never forgive being slighted in that way, although [she would] not have gone on any count.

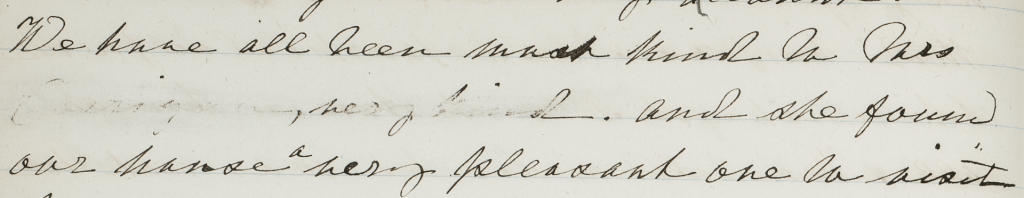

We have all been most kind to Mrs [Corrigan], very kind. And she found our house a very pleasant one to visit. I am much mistaken if she is ever asked to enter it again. (21 May 1889)

There may have been considerable sympathy in the community for Deborah Corrigan in the wake of Cornelius’ conviction, especially considering she may have been raising her children without the help of a husband for some time. This is probably what Emily means when she notes that they have ‘all been most kind’ to her.

Mrs Corrigan continued her theatre interests in Nelson. In 1887 she performed in concerts at the Wood Sunday School, at the All Saints’ Institute, and at a Christ Church Ladies’ Guild event. Her acting talents are also praised in the papers: the Colonist calls her portrayal of Barbara Jones in an 1889 production of the melodrama ‘The Charcoal Burner’ ‘a decided success.’ In 1890 the Nelson Evening Mail says ‘Mrs Corrigan acted the part of Mrs Wiggleton with much spirit’ in the farce ‘The Lion Slayer,’ and that she ‘infused considerable spirit’ into her role as Mrs Crincum in ‘The Wandering Minstrel.’

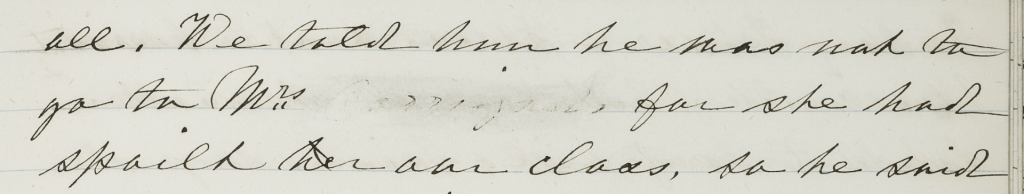

If I had read the passage in Emily’s diary without knowing Deborah Corrigan’s story, I may have thought very differently about the dance class thief. Having discovered a little of what she experienced in her marriage, I suspect that her conduct over the dance classes was not malicious but rather the consequence of seeing a good idea, knowing she had the skill to execute it, and needing the money it would bring in. Emily Harris seems to have come to a similar conclusion. In the margin of the first page in her diary mentioning the dancing class story, Emily later adds: ‘I erase her name because we forgave her long ago.’

Deborah Corrigan died at her home in Nile St East, Nelson, in 1894, aged 46. Her son Dominic Harewood Lascelles Corrigan worked as an accountant in Nelson in the 1890s and later lived in Dunedin. In 1910 he married Florence Lucy Leary of Palmerston North. Beatrice Alice Corrigan attended the Hardy St Girls’ School and then Nelson Girls’ College. In 1903 she passed an examination in Nelson for the Civil Service. She died in Hawke’s Bay in 1951. Cornelius Fookes Corrigan may have died in Australia at Broken Hill in 1902, aged 45.

Lead writer: Dasha Zapisetskaya

Research support: Michele Leggott, Brianna Vincent

Fascinating! Love the serendipity of recognising the redacted name.

I have been researching my family tree and Deborah Blake is my great grand father’s sister. I have been fascinated by her story and also that of her grand daughter Lascelles Corrigan Verbi. Not sure if there is any connection to Admiral Blake because Robert Blake (1816-1882) had a son William Blake (1840-1914) my great grand father and he had a son Charles Minden Blake (1879-1942 and he had 3 sons the eldest Minden Vaughan Blake (1913-1981) an outstanding Battle of Britain Pilot and inventor.