By Michele Leggott

Everyone in Nelson knows that Miss Harris of Nile St is on the lookout for interesting plants to paint. Friends bring or send floral offerings and she records the gifts in her diary:

Survey Camp, Rainbow River

April 8th 1886.Dear Miss Harris,

As Mr Ward, my assistant, is going down to Nelson to get up some stores etc., I thought perhaps you might like to have this bundle of mountain moss that I happen to have in the camp with me. Had I known we should have had to send before I would have tried to get you a better lot.In haste,

Yours faithfully,

Stephenson Smith.

Mrs Gillam brought me some pieces of nikau berries, which her husband & Mr Worsley had got during their trip to Pelorus Sound. They could not get the whole branch of berries, Mr Worsley was obliged to stand up against the tree on Mr Gillam’s shoulders to get a bit, however I am very much obliged to them for their trouble. (28 Apr 1886)

Went out to Bishopdale one Saturday morning & took a sketch of the fan palm, had dinner there. Saw some most beautiful coral which the Bishop has just brought from Fiji. The Bishop showed me his sketch book, he has a facile pencil. I was longing for a little bit of blossom of the palm to paint when the Bishop offered me a piece. So on Monday morning he sent me a large piece, a piece of which I have painted & made a longer sketch of the rest. I am now waiting for a leaf to finish the picture.

19th. The Bishop brought me two leaves of the fan palm, so now I must do my utmost to make my picture a success.

20th, Saturday. Worked very hard all the morning until eleven a.m., then spent two hours sketching in the fan palm leaves. (17-20 Nov 1886)

No trace of Bishop Suter’s fan palm survives among Emily’s paintings. But Frank Stephenson Smith’s mountain moss (Raoulia eximia) aka vegetable sheep turns up in a family exhibition. The painting is admired by a local reviewer who knows what he is looking at: ‘the mountain moss, which has many a time been taken for sheep on a hill side, and caused an inexperienced shepherd a long and useless walk.’ (Nelson Evening Mail 25 Nov 1889: 2) And the nīkau berries gymnastically procured by Mr Gillam and Frederick Worsley? Emily’s diary records the sale of a painting to Oswald Curtis en route from New Plymouth to Stratford by train in 1890:

At Inglewood we stopped for a short time. I had Oswald Curtis’s picture, which I delivered to Gretchen who came to the door of the carriage as I did not get out, then I stood at the step for a few minutes talking to Oswald Curtis about my Ex. etc. I happened to mention that Mrs Curtis liked the Nikau berries so he asked the price.

‘One pound,’ I replied.

‘Then give it to my mother from me.’

But Emily had painted the berries of the nīkau palm well before she received the specimen from Pelorus Sound.

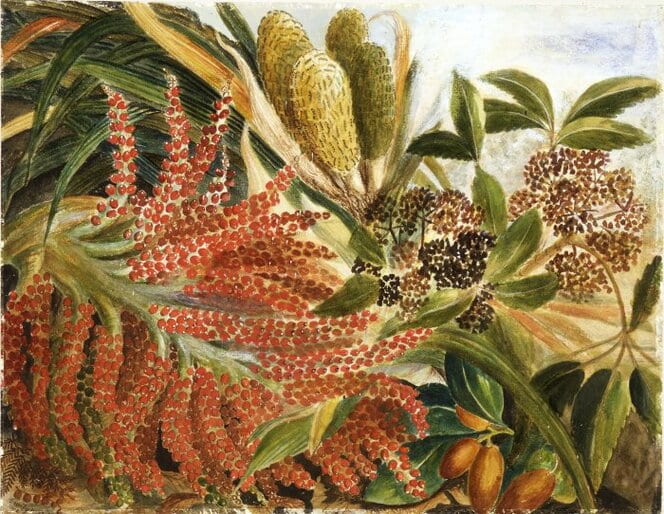

A large branch of orangey-red nīkau berry clusters reaches across a 1879 watercolour from the lower left corner, taking up nearly half the composition. Two smaller clusters of inky purple whauwhaupaku berries draw the eye further right again, almost to the edge of the frame. Below them are four fat orange karaka berries. Above are four fruits of the kiekie painted in muted greens and browns. Leaves of the whauwhaupaku, karaka and kiekie surround the fruits and berries.

By 1890 Emily’s botanical interests were tending towards the flowers to be found in the alpine and sub-alpine regions of Taranaki, Nelson, the West Coast and Fiordland. Her enthusiasm for mountain flowers got its start during the five days she camped out on the lower slopes of Mount Taranaki in January 1890. It culminated in the artist’s book of 28 watercolours and two cover designs that she produced between 1894 and 1910. The preface of New Zealand Mountain Flora describes her delight in the flowers she found on Mount Taranaki and its subsequent transformation into the study of their classification and habitat:

The forest flowers were nearly over but in the adjoining scrub were many flowering plants, the most beautiful of these, Ourisia macrophylla grew plentifully under the bushes and in sheltered rocky crevices. Farther on among the tussock grass and stones grew quantities of yellow Ranunculus with unusually fine glossy leaves. Down the steep sides of the mountain grew masses of white everlastings, pale-blue harebells, small white celmesias and many other lovely flowers. I was fortunate to be able to paint them while fresh, and to see for myself how they grew. Since that time I have added continually to my collection, every season bringing something new.

I have camped on the Dun Mountain line and found many interesting plants on and near the mineral belt. Also at a lovely mountain lake where Alpine Flora abounded.

Thus year by year the number and variety of specimens had gone on increasing until it seemed a pity that such a collection should be hidden away in portfolios known only to a few especially as yet, no one has published drawings devoted entirely to New Zealand Mountain Flowers. With this idea I have worked for some years, and have now I hope, completed sufficient illustrations to be of interest to those who love to explore the mountain regions, and to remind them of flowers they may have passed on their way, and to those also who never expect to behold these children of the mists and snows in their native haunts.

https://natlib.govt.nz/records/22878573

The preface ends with the names of those who supplied plants for the growing collection at Nile St:

My sincere thanks are due to many kind friends who have sent me specimens of Alpine and Sub-Alpine species – the late Professor Kirk, Messrs R.I. Kingsley, D.W. Bryant, W. Townson, F.G. Gibbs, and others.

The list of names is a key to Emily Harris’s conversations with the scientific gentlemen around her. It is impressively close to biographer Eric Godley’s evocation of Nelson botanists and plant collectors of the day:

Had the Nelson Botanical Society begun—let us say— in 1890, it is a fair bet that the following would have been foundation members:

- The Right Reverend Andrew Burn Suter (1830-95) Bishop of Nelson, and patron of the arts and sciences. He is commemorated in the native daphne Pimelea suteri Kirk (1894)

- Dr Leonard George Boor (1825-1917) surgeon and Medical Superintendent at the Nelson hospital, the mental hospital, the immigration barracks, the old people’s home, and the gaol, who gave botany lessons at Suter’s Bishopdale Theological College. (The Bishop believed that botany would train the students in analytical reasoning, presumably envisaging exercises in identifying plants using so-called ‘keys’)

- Mr Robert Ingpen Kingsley (1846-1912) Secretary-Treasurer of the Anglican Diocese, Nelson, and naturalist, whom I wrote about in the last Newsletter, and two young schoolteachers:

- Mr William Henderson Bryant (1864-1948) headmaster of the Brightwater School and (later) Kingsley’s brother-in-law, the subject of the present note

- Mr Frederick Giles Gibbs (1866-1953) then an assistant master at Nelson College, later headmaster, the Nelson Boys’ School, who became the leading Nelson botanist of his time. The following would have been candidates for country membership.

- Mr James Dall (1840-1912) then at Collingwood (later at nearby Rockville), the plant and animal collector

- Mr William Lewis Townson (1855-1926) chemist and druggist, Palmerston Street, Westport, from 1888, who (like Dall, Kingsley and Bryant) collected for both Kirk and later Cheeseman. (NZ Botanical Society Newsletter 71, Mar 2003)

Can we catch glimpses of the input of these gentlemen in Emily’s work?

In 1889 Dr Leonard Boor was her checkpoint for the drawings that would be published as New Zealand Flowers, Berries and Ferns the following year:

Wednesday. Finished my drawings & took them up for Dr Boor to look over.

Saturday. […] In the afternoon Milly Boor brought back my drawings, she said she waited until the last minute because her father wished himself to bring them but was detained, he sent to say that he had corrected a few slight errors. With the drawings he was perfectly charmed. I was very much pleased to hear that. (3-6 July 1889)

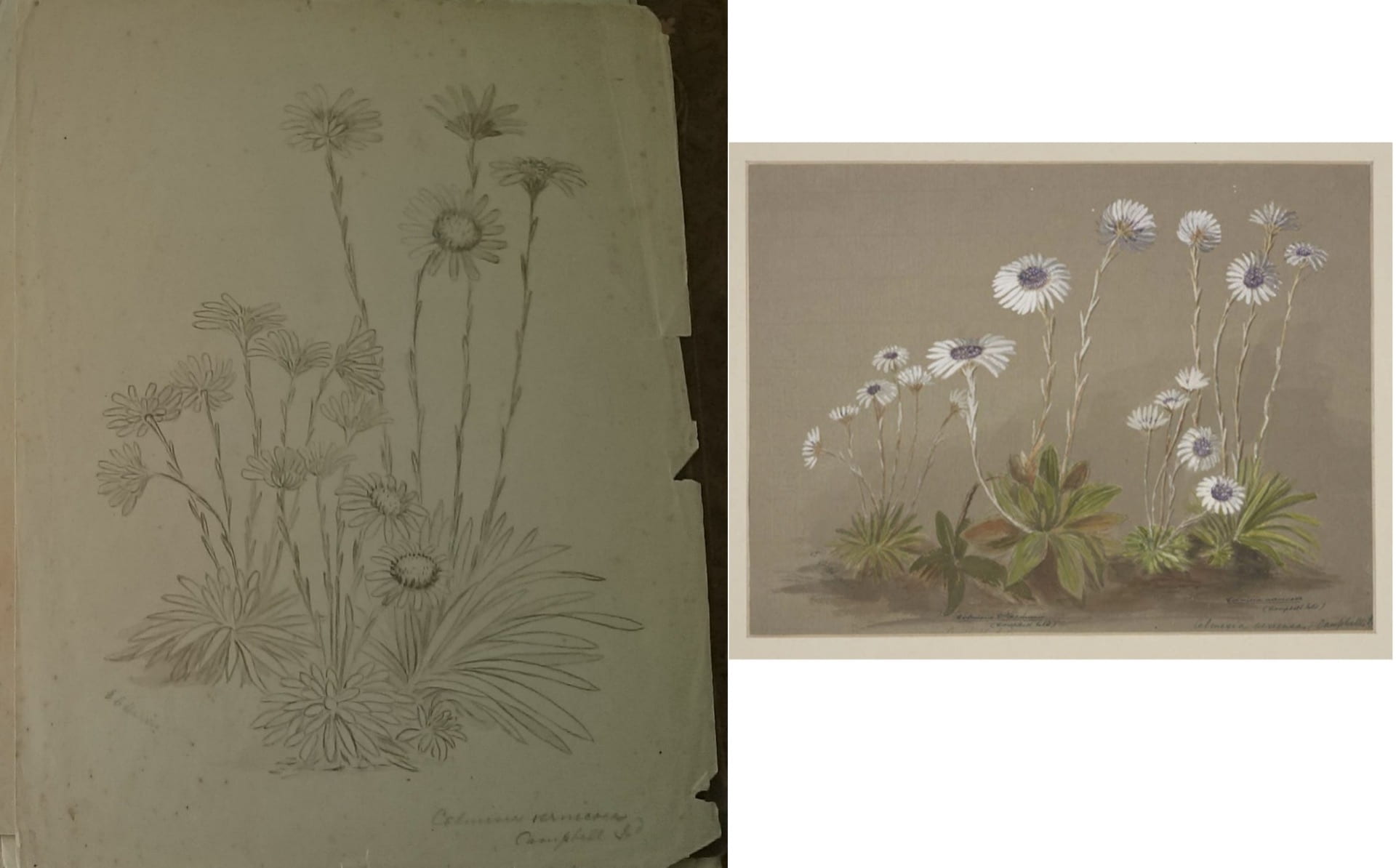

In 1890 botanist and Keeper of the Wellington Botanic Garden, Thomas Kirk, made collecting trips to the Snares, Auckland, Campbell and Antipodes islands. Emily was able to draw specimens from the collection when she was invited to Kirk’s home in October that year. Celmisias (mountain daisies) from Campbell Island and Dusky Sound were sketched in Kirk’s study and later painted in watercolour and bodycolour. Two of them, Celmisia chapmanii and Celmisia vernicosa, travelled on to the Natural History Museum in London in 1893. Another, Celmisia holosericea, is at Turnbull, inscribed ‘Dusky Bay,’ echoing the label of Kirk’s specimen of the plant, now at Te Papa. The Dusky Bay celmisia also appears in New Zealand Mountain Flora.

William Townson is directly quoted in New Zealand Mountain Flora from a letter sent to Emily with specimens of the white gentian that Thomas Cheeseman renamed in his honour around 1906:

‘I send you some specimens I gathered on Mt. Rochfort. The large white flowered one is Gentiana obovata (new species). It grows at an elevation of 3000 ft. and the radical leaves are like rosettes, and several stems grow from one root, forming a most beautiful clump.’ Gentian obovate now G. Townsoni. (NZ Mountain Flora)

In addition to Townson’s gentian in New Zealand Mountain Flora, Emily produced a watercolour and a bodycolour of a species from Dun Mountain that she identified as Gentian gentiana. The bodycolour, on green paper, was sent to London with her celmisia paintings in 1893.

Botanical contributions by Robert Kingsley, William Bryant and Frederick Gibbs to Emily’s work are harder to spot. Kingsley’s location of whau (Entelea arborescens) growing south of its known range and reported to Kirk, is probably the source of Emily’s paintings of the tree noted by the Nelson Evening Mail in 1899 and 1906. The paintings themselves have disappeared. Kingsley and Bryant often collected together in coastal and mountain regions of Nelson, as did Bryant and Gibbs. It is tempting to think that the watercolour of Gnaphalium bellidioides, Ligusticum aromaticum and Cyperus ustulatus, with its inset view of a campsite and mountains (and an accompanying poem), references the scientific gentlemen on their botanical wanderings. Alternatively, Emily’s gender-neutral styling of herself as EC Harris in one of the cover designs for New Zealand Mountain Flora leaves open the possibility that she is part of this and other field work in the hinterlands of Te Waipounamu.

Gnaphalium bellidioides, Ligusticum aromaticum, Cyperus ustulatus. New Zealand Mountain Flora

Gnaphalium bellidioides, Ligusticum aromaticum, Cyperus ustulatus. New Zealand Mountain Flora

Let us camp on the hill-side

The valley below

The mountains afar

With their clouds and their snow.

The blue sky above us

The stream flowing near

With our pipe and our dog,

And our comrade so dear.

We’ll dream that the way

Unto Paradise lies

Where yonder green hill

Meets the clear shining skies.

You continue to astonish with your research. Thank you