By Catherine Field-Dodgson

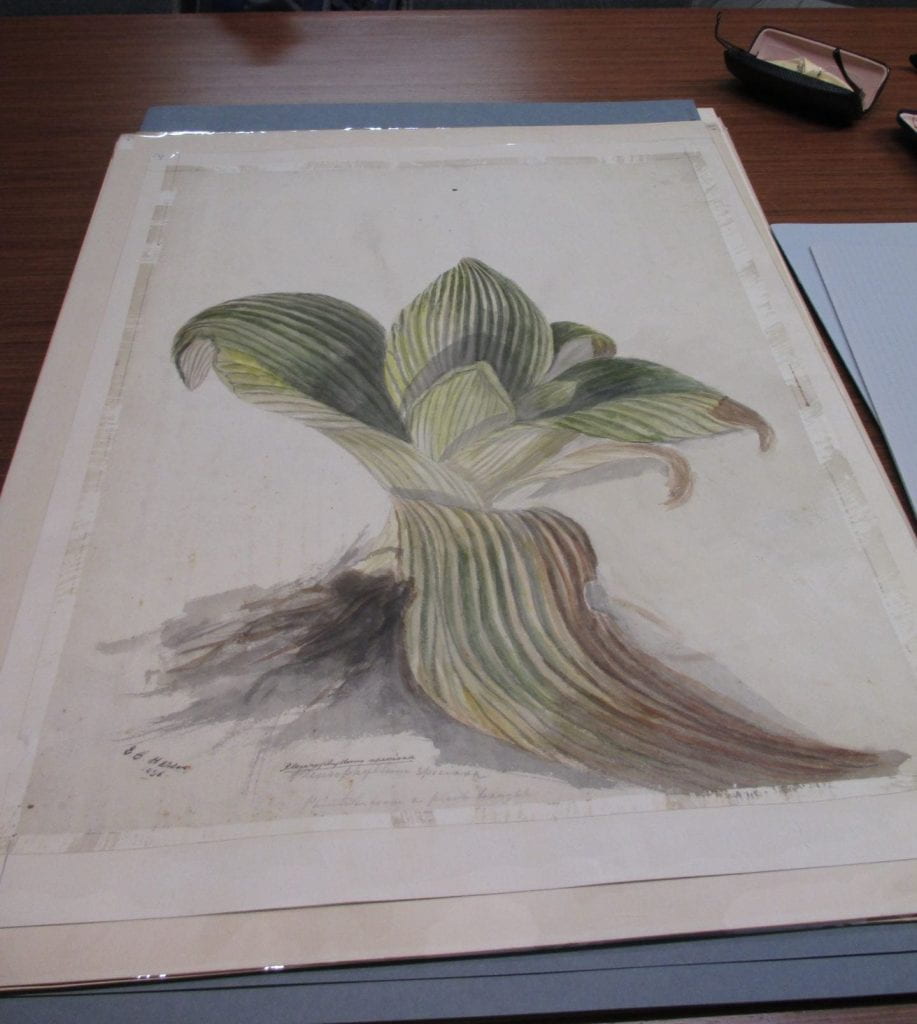

Nestled amongst the collection of Emily Harris watercolours at the Turnbull Library in Wellington is a large painting of a weird plant with huge green leaves. Bearing more than a passing resemblance to an overgrown cabbage, or something out of The Day of the Triffids, it’s certainly not a commonly-seen plant in Aotearoa.

The pleurophyllum, also known as a ‘mega herb’, the Campbell Island daisy or Great Emperor daisy, is endemic to the sub-antarctic islands of New Zealand, which are located 465km to the south of the South Island. Its thick, leathery leaves evolved in the cold harsh climate there. So how and why was Emily painting a species of plant that came from such a distant location? The answer comes in a clue on the lower part of Emily’s painting. Emily has carefully written in pencil: ‘painted from a plant brought [by Mr E. Lukins, from Adams Island, Auckland Islands].’ The information about Lukins was written on the old mat and mount of the watercolour, and has been transcribed by Turnbull librarian Janet Paul.

SS Hinemoa in the subantarctic islands, New Zealand. Pollock album. Ref: PA1-f-049-21-2. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

In May 1896, Edward Herbert Lukins (1861-1931) boarded the New Zealand Government steamship Hinemoa bound for the Snares, Auckland, Campbell, Antipodes and Bounty Islands. He was dispatched by the Nelson Philosophical Society with the express purpose of collecting specimens for the Nelson Museum. Founded in 1883 to share scientific research and knowledge (principally for men), the Nelson Philosophical Society linked back to the New Zealand Institute, which later became the Royal Society of New Zealand. Meetings were regularly held in the evenings, and local Nelson gentlemen gathered to present and discuss various scientific findings which were then written up in Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. By travelling by Government steamer to the sub-antarctic Islands, Lukins was fulfilling a scientific brief of many early colonists: to document and collect as many different specimens as possible.

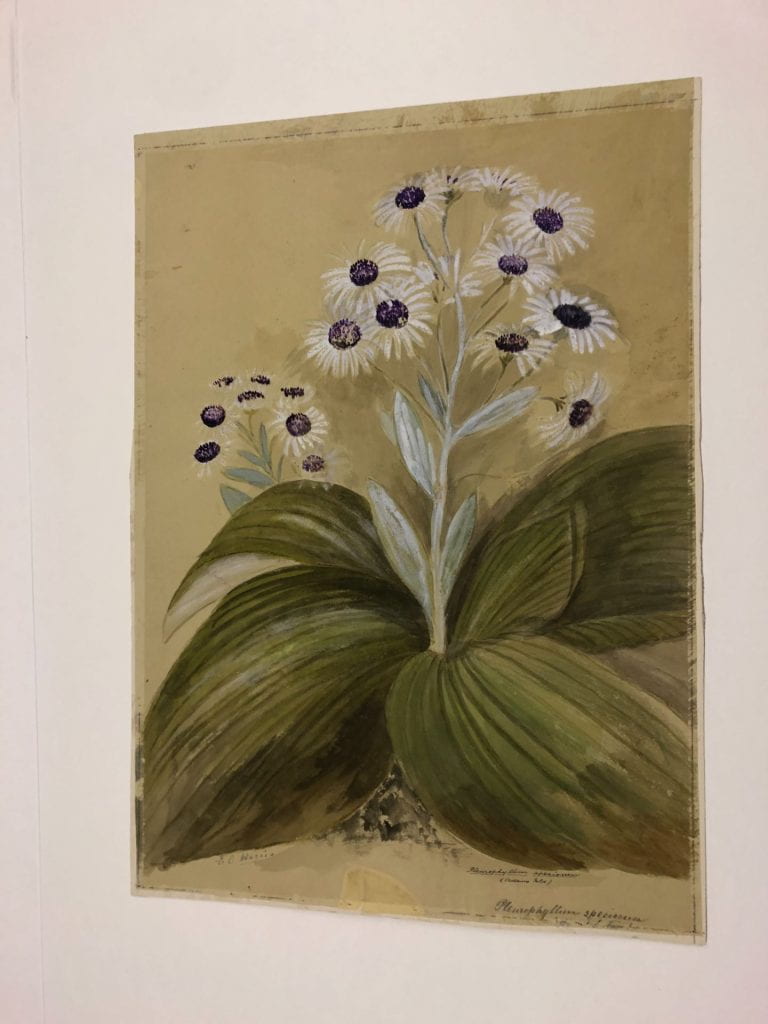

While exploring the Auckland Islands, Lukins visited the area named ‘Fairchild’s Garden’ on Adams Island – a vast meadow of 400 acres of flowering sub-antarctic plants, including the purple-flowering pleurophyllum. In 1890 Professor Thomas Kirk and F. R. Chapman named this part of the island after the popular steamship captain John Fairchild, who was celebrated for steering steamers to difficult sites, dropping off enterprising botanists on their expeditions. Upon seeing it for the first time, Chapman remarked that Fairchild’s Garden was “one of the most wonderful natural gardens the extra tropical world can show”, as before him lay “… the most beautiful field of flowers I had ever seen”. (Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 1890: 505-506). Kirk wrote several papers about his sub-antarctic discoveries, and noted of the pleurophyllum: “As the traveller walks amongst them his feet crash through the horizontal leaves as though he were walking on thin ice.” (The Australiasian Association for the Advancement of Science, 1891:220) Because Lukins visited Fairchild’s Garden a little later in the year, the meadow was not in flower, but he noted: “At the time of our visit the gardens alas bore its winter aspect, but one of our party, when looking over acres of the garden, said “Why its Fairchild’s kitchen garden,” and he likened some of the most beautiful things to cabbages, others to huge celery, and still others to rhubarb.” (Round Southern Isles, 1896: 11)

Like Kirk and Chapman before him, Lukins returned with a considerable haul:

The Nelson Mail says Mr. Lukins has brought back an interesting collection of sub-Alpine plants, besides geological specimens and a large number of birds, including an albatross measuring 14 feet from tip to tip of its wings, and another measuring 11 feet. He also brought two live rare specimens of the all-green paroquet from the islands, which will most likely be presented by the society to the Queen’s Gardens. Mr. Lukins was not successful in his search for sea shells, and says the shores of the islands are not to be compared with those of Cook Strait for shells. (Evening Post 2 June 1896: 4)

The two green parakeets ‘collected’ by Lukins were displayed in the Queen’s Gardens in Nelson: ‘The Mayor said the caretaker’s wife was teaching the birds to talk and dance, and one was more intelligent than the other, but both were learning fast and proving a great attraction. (Nelson Evening Mail 13 June 1896: 2) Mr Robert Kingsley, fellow member of the Nelson Philosophical Society and a good friend of Emily’s, stated that the birds were patently kidnappable: ‘They are very tame and easily caught, and are found generally among the tussocks or grass. (Nelson Evening Mail 3 June 1896: 2)

After presenting the parakeets to Nelsonians, Lukins gave some of his Auckland Island botanical specimens to Emily to paint. By October the same year, a number of his specimens were growing well in Nelson, and it is highly likely that Emily would have been able to view these as well:

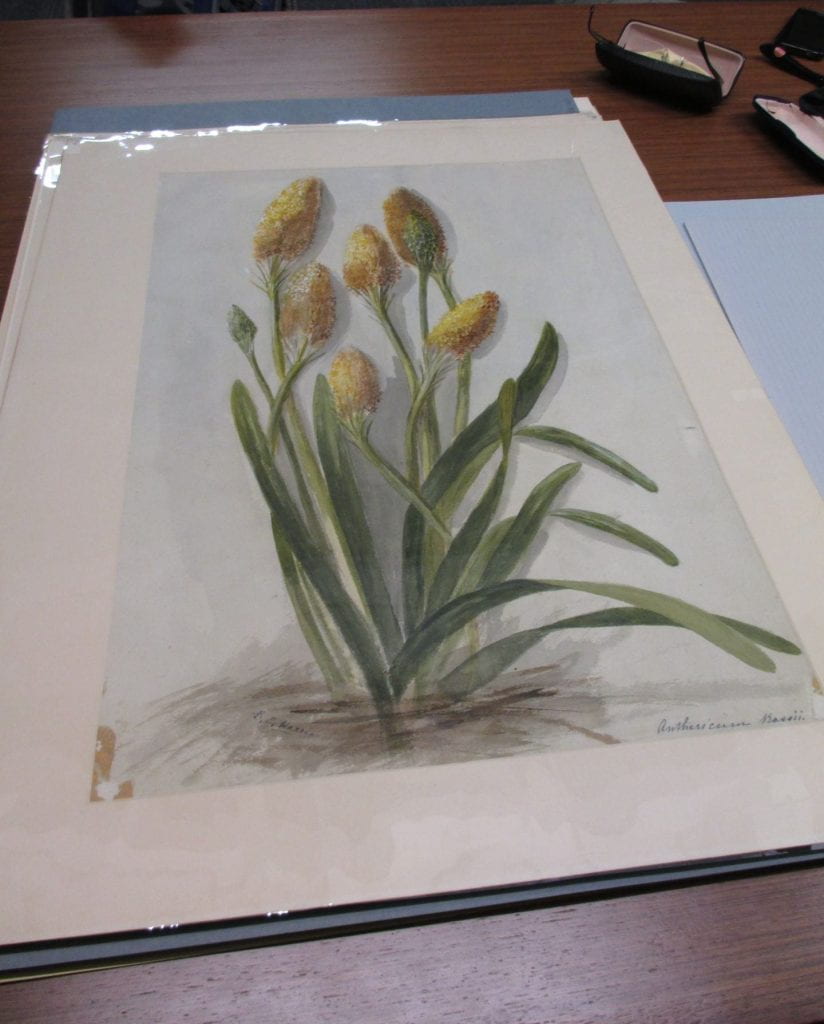

We understand that the specimens brought by Mr E. Lukins of the Island flora planted at Bishopdale are growing very well. One Anthericum Rossii is just coming into flower, It belongs to the order Lilliacat, and is only found growing in the Auckland Islands. (Colonist 20 October 1896: 2)

As Michele noted in Talking to the Scientific Gentlemen, the 1890s period saw Emily frequently dealing directly with botanists and collectors. On 30 November 1896, she presented a collection of ‘coloured sketches of flowers from the southern islands’ to the Nelson Philosophical Society (Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute 1896: 636):

At the annual meeting this week the table was filled with more than usually interesting specimens. The birds collected by Mr Lukins from the Southern Islands were a great feature, the young Royal Albatross in snow white down being a striking object. A very remarkable fish callorhynchus an actius was also exhibited. On the walls were some beautifully painted sketches of the flowering plants of the islands by Miss E Harris. These were explained by Mr Kingsley. The President stated that the plants at Bishopdale collected by Mr Lukins were growing remarkably well; several had flowered and were most interesting. (Nelson Evening Mail 2 December 1896: 2)

Emily’s paintings must have been a truly impressive sight that evening, not only because she had painted an array of colourful and unusual plants but because of their exceptionally large size. The mega-herbs would have been new to most members of the Society.

Emily’s studio was described in detail in a Nelson Mail article later that same month, with attention focused on her more uncommon paintings:

Miss Harris has had rare opportunities of studying the vegetation of the New Zealand forests, for not only has she visited most of the localities where grow the ferns, berries, flowers, and foliage she has painted, but the botanists of the colony consider it an honour and a pleasure to send her specimens from all parts of New Zealand. Thus, she can show side by side a flower growing at the extreme north of these Islands, and another growing at the extreme south. When Professor Kirk returned from the Auckland Islands in the Hinemoa he brought several valuable specimens, from which Miss Harris took paintings. She was then enabled by Mr Lukin to add the foliage from the plants, etc., which he collected during his recent tour. The pictures are in both oil and water colours, and range from the smallest to the largest size. (Nelson Evening Mail 23 Dec 1896: 2)

The following year in 1897, Emily made another appearance at the Nelson Philosophical Society:

Miss E. Harris, of Nile street, whose skill as a painter of New Zealand flowers is so well-known, kindly lent a beautiful colored sketch of some of the flowers collected by Mr Kingsley. This was greatly and most deservedly admired, and the thanks of the Society were tendered to Miss Harris. A unanimous vote of thanks was given to Mr Kingsley for his graphic and pictorial description of his trip, which was an able demonstration of the valuable aid of the camera in trips made to unfrequented, or, to most people, inaccessible districts. (Colonist 31 Aug 1897: 2)

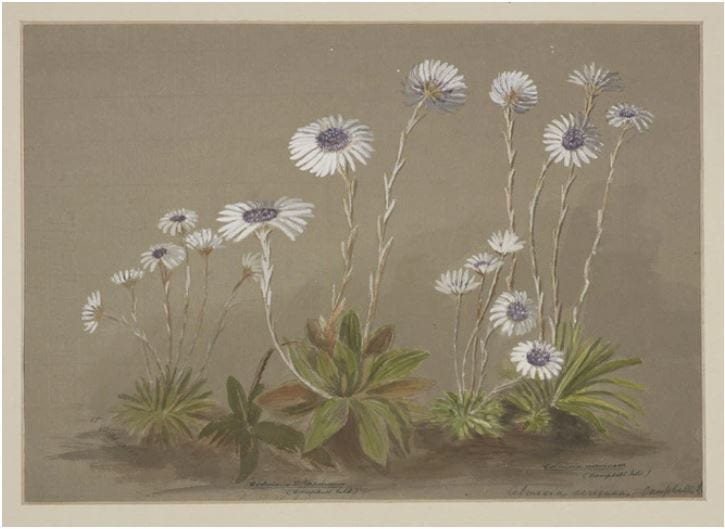

These appearances at the Philosophical Society are significant as they illustrate that Emily had interests outside the Suter Art Society, and they demonstrate her artistic skills and ambitions. Emily is not just painting well-known New Zealand plants – she is documenting unusual specimens from far-flung islands in a time before photography was widespread. While it is difficult to identify which paintings she might have made from Kingsley’s sub-alpine specimens, a number of her sub-antarctic paintings can be found in the Turnbull Library’s collection. Interestingly, the 1896 Pleurophyllum speciosa from Adams Island was part of Alexander Horsburgh Turnbull’s personal collection. Another large sub-antarctic watercolour, Anthericum Rossii, also derives from this source. The balance of Emily’s sub-antarctic works at the library were purchased by Johannes Anderson in 1924.

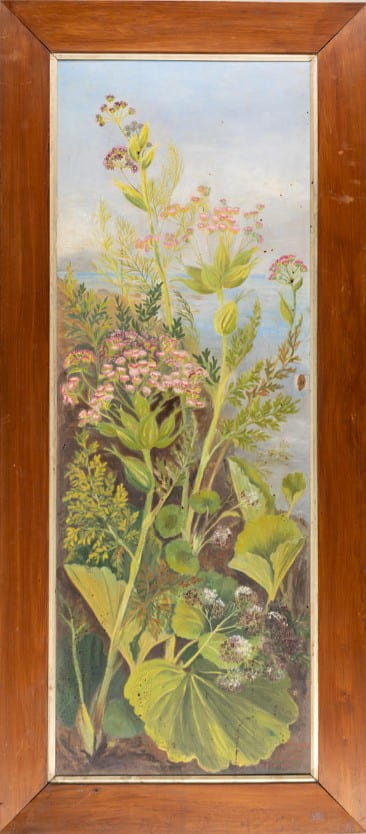

By 1906, Emily had painted two large oil panels featuring sub-antarctic plants for the Christchurch International Exhibition, for display in the Nelson Court. One of these panels now resides in the collection of the Puke Ariki museum, in New Plymouth. It is a large, framed oil painting, and depicts Aralia lyalli [Stilbocarpa lyalli], Ligusticum latifolium [Anisotome latifolia], and Ligusticum antipodium [Anisotome antipoda] all growing together in a natural environment, with a sliver of sea and sky in the background. These are all species of plants that Emily had earlier rendered in watercolours. The whereabouts of Emily’s second panel is currently unknown, but based on her surviving watercolours, it is possible that the missing panel depicts one or two pleurophyllum species, some specimens of celmisias, and perhaps the red-hot poker-like flower Anthericum rossii, which grew well in the garden at Bishopdale for some time.

Here are seven more of Emily’s sub-antarctic paintings at the Turnbull Library. Some have not been digitised and are protected by mylar covers. We have photographed them as best we could to avoid any reflections.

Several of the plant paintings were made into and sold as prints. Some are on display in Melrose House, Trafalgar Street, South, Nelson.

Thanks Cheryl – that’s great to know that some of the Turnbull prints are in Nelson. They’re lovely prints and we managed to get a set for Michele on Trademe recently